Link para o artigo original : https://www.lordabbett.com/en-us/financial-advisor/insights/markets-and-economy/why-aren-t-high-yield-spreads-wider-.html

Insight • October 25, 2022

Why Aren’t High Yield Spreads Wider?

Amid concerns about U.S. economic growth, the timing and trajectory of U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed) rate hikes, and where inflation may be headed next, we often get a sense from investors that they have a gut feeling that high yield spreads should be wider than they currently are. The thinking goes, “With a recession likely, spreads should be widening out to at least 700-800 basis points (bps)—heck, maybe a thousand.” The corollary, of course, is that the prospect of wider spreads makes high yield a less-than-attractive place to put one’s money right now. Noting the option-adjusted spread on the representative ICE BofA U.S. High Yield Index at 501 basis points (bps) as of October 21, approximately 40 bps tighter than its long-term average, only heightens the confusion.

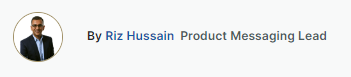

You may have seen simple charts like Figure 1, showing an overlay of high yield spreads (represented by the Bloomberg US High Yield Corporate Index: inverted left axis) versus the S&P 500 (right axis), suggesting the same—high yield spreads “should” be wider at these stock price levels:

Let’s put aside questions of the relevance of 1) comparing absolute levels of risk premiums (credit spreads) directly with asset prices (in this case, equities) over any reasonably long period of time, and 2) the constituent differences between the S&P 500 and the high yield market. Is there something else that can explain why spreads seem somewhat sticky at current levels? Credit spreads are appreciably tighter than the widest levels of the year seen in early July, whereas the improvement in the S&P 500 since mid-year lows has been more muted.

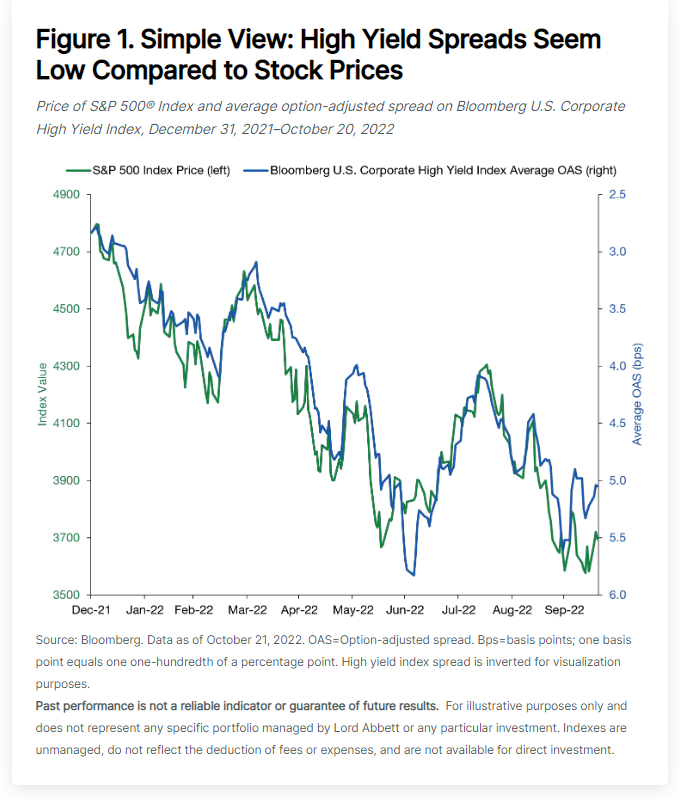

At times of rising financial market stress, credit investors want to get a handle on the potential downside for their holdings. For high yield, the conversation switches from one purely about risk premiums (i.e., credit spreads that capture premiums for potential default loss, liquidity, and other factors) to convexity and dollar prices. This pivot leads to thinking about upside (to par at maturity) or downside (to recovery, in case of default) of bonds. Figure 2, derived from weekly data over the past 20 years, shows the high yield market recently plumbing the depths of dollar prices last seen in the post-global financial crisis period of 2008–09.

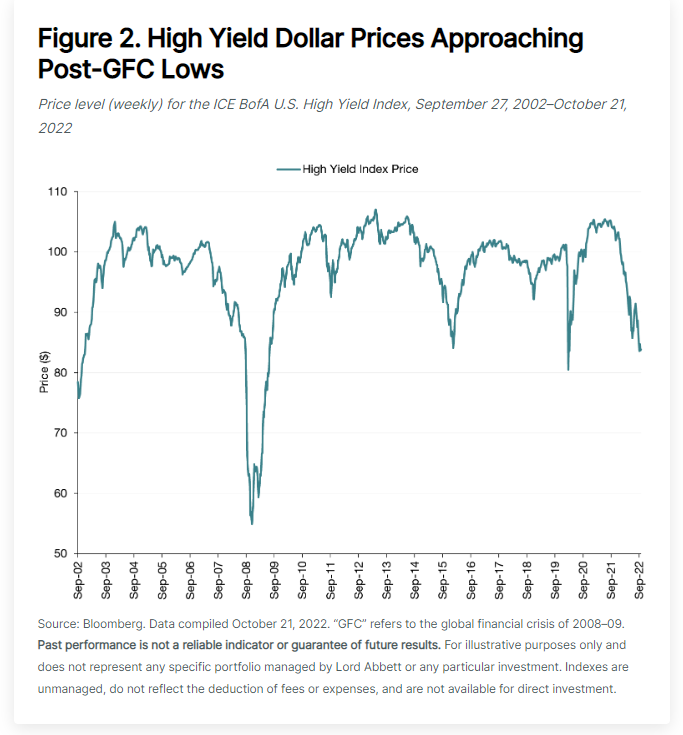

How did we get here? Obviously, there has been some spread widening, year to date, but clearly the bigger climb in benchmark Treasury yields has hit dollar prices harder: high yield spreads are wider by 190 bps from the start of 2022, but five-year Treasury yields (most closely matching the duration of the high yield market) are higher by 310 bps. In the past, when investors have had widespread concerns about credit markets, or the macro environment, Treasury yields typically have rallied (on factors such as a flight to the safety of U.S. government debt, expectations of Fed easing, etc.). Those are countering effects on the dollar price of high yield bonds. We’ve had just the opposite this time around. Specifically, given the worries around persistent inflation that have not vexed investors for many decades to the same extent, the correlation of U.S. Treasury bond prices and risk assets has flipped to positive . Worries about inflation have led to lower government bond prices and lower prices for risk assets. Figure 3 details the relationship between high yield dollar prices and spreads over the last 20 years:

The callout arrow in the chart points to index levels as of October 21: spread at +501 bps, price at $83.86. We have a couple of observations:

- At similar spreads, dollar prices are basically the lowest they have ever been over the past 20 years: the median index price when spreads have been in the range of 450-550 bps, bracketing today’s level, has been $100.31. So, if the conversation for investors has at all switched to wondering about downside versus upside, we are a lot closer to historical average recovery levels today than we’ve been at similar spreads in the past.

- Alternatively, when dollar prices have been this depressed, spreads typically have been much wider: the median index spread when prices have been in the range of $80-$90, loosely bracketing today’s level, has been 787 bps. That’s very close to the 800-bps level at which many investors have “felt” they can more safely buy into high yield in the past.

Clearly, part of the allure of depressed dollar prices in high yield today rests on some assumption around recovery levels. We believe the peak in the default rate will not reach levels typically associated with a recession. Similarly, we believe recovery levels could hold reasonably well as a result (better than experienced during the pandemic period), even as the trailing default rate climbs. Most notably, we believe any defaults to come will be broadly distributed across sectors, not concentrated in any one sector like energy, as witnessed in the prior two cycles. This lack of concentration, along with better-than-typical default dynamics should support recoveries for bond investors in our view. This highlights the importance of acknowledging the shrinking gap between current high yield index prices and downside in default.

Summing Up

This conundrum of the rise in both benchmark yields and credit spreads has some interesting implications, creating a disconnect between spreads and dollar prices that many investors feel today. We have previously discussed why the current composition of the high yield market may preclude spread valuations reaching levels typically experienced in growth slowdowns. But high yield bond prices are already at levels that investors have typically associated with those growth slowdowns, given the outsized move in benchmark yields this year. We believe this reality creates the conditions for both historically attractive yields and positive convexity at current bond prices, despite credit spreads that have held in reasonably well. More broadly, when evaluating the opportunity in credit today, we believe investors should consider not only spread, but price as well, creating attractive total return dynamics going forward.

As informações aqui contidas estão sendo fornecidas pela GAMA Investimentos (“Distribuidor”), na qualidade de distribuidora do site. O conteúdo deste documento [e informações neste site] contém informações proprietárias sobre LORD ABBETT e o Fundo. Nenhuma parte deste documento nem as informações proprietárias do LORD ABBETT ou DO Fundo aqui podem ser (i) copiadas, fotocopiadas ou duplicadas de qualquer forma por qualquer meio (ii) distribuídas sem o consentimento prévio por escrito do LORD ABBETT. Divulgações importantes estão incluídas ao longo deste documento e que devem ser utilizadas exclusivamente para fins de análise do LORD ABBETT e do Fundo. Este documento não pretende ser totalmente compreendido ou conter todas as informações que o destinatário possa desejar ao analisar o LORD ABBETT e o Fundo e/ou seus respectivos produtos gerenciados ou futuramente gerenciados. Este material não pode ser utilizado como base para qualquer decisão de investimento. O destinatário deve confiar exclusivamente nos documentos constitutivos de qualquer produto e em sua própria análise independente. Nem o LORD ABBETT nem o Fundo estão registrados ou licenciados no Brasil e o Fundo não está disponível para venda pública no Brasil. Embora a Gama e suas afiliadas acreditem que todas as informações aqui contidas sejam precisas, nenhuma delas faz qualquer declaração ou garantia quanto à conclusão ou necessidades dessas informações.

Essas informações podem conter declarações de previsões que envolvem riscos e incertezas; os resultados reais podem diferir materialmente de quaisquer expectativas, projeções ou previsões feitas ou inferidas em tais declarações de previsões. Portanto, os destinatários são advertidos a não depositar confiança indevida nessas declarações de previsões. As projeções e/ou valores futuros de investimentos não realizados dependerão, entre outros fatores, dos resultados operacionais futuros, do valor dos ativos e das condições de mercado no momento da alienação, restrições legais e contratuais à transferência que possam limitar a liquidez, quaisquer custos de transação e prazos e forma de venda, que podem diferir das premissas e circunstâncias em que se baseiam as perspectivas atuais, e muitas das quais são difíceis de prever. O desempenho passado não é indicativo de resultados futuros.