Link para o artigo original:https://www.bridgewater.com/research-and-insights/where-can-investors-find-geographic-diversification-today

Maximizing the benefits of geographic diversification can be highly beneficial for portfolios. But doing so can be difficult because many economies are closely linked to US conditions, making their markets highly correlated to US assets investors already own. In this report, we walk through some of the markets we see as most diversifying.

Geographic diversification is one of the cheapest ways for investors to make their portfolios more robust. Today, most investors are overly concentrated in US assets, particularly after a decade of US equity outperformance. But even when accounting for this outperformance, a simple geographically diverse portfolio (weighting economies equally) has performed in line with US-dominated portfolios and has been less volatile. While the US could continue to have the best-performing assets in the world for the next decade, past outperformance has now been discounted, raising the hurdle going forward.

But while geographic diversification is desirable in theory, maximizing its benefits can be difficult in practice. The most diversifying markets are those where the key drivers of asset prices—growth, inflation, and monetary policy—are lowly correlated to other economies. But because the US is the largest economy in the world, by far the largest importer of goods, and a large capital provider, it tends to influence those drivers in other markets, limiting their diversification potential.

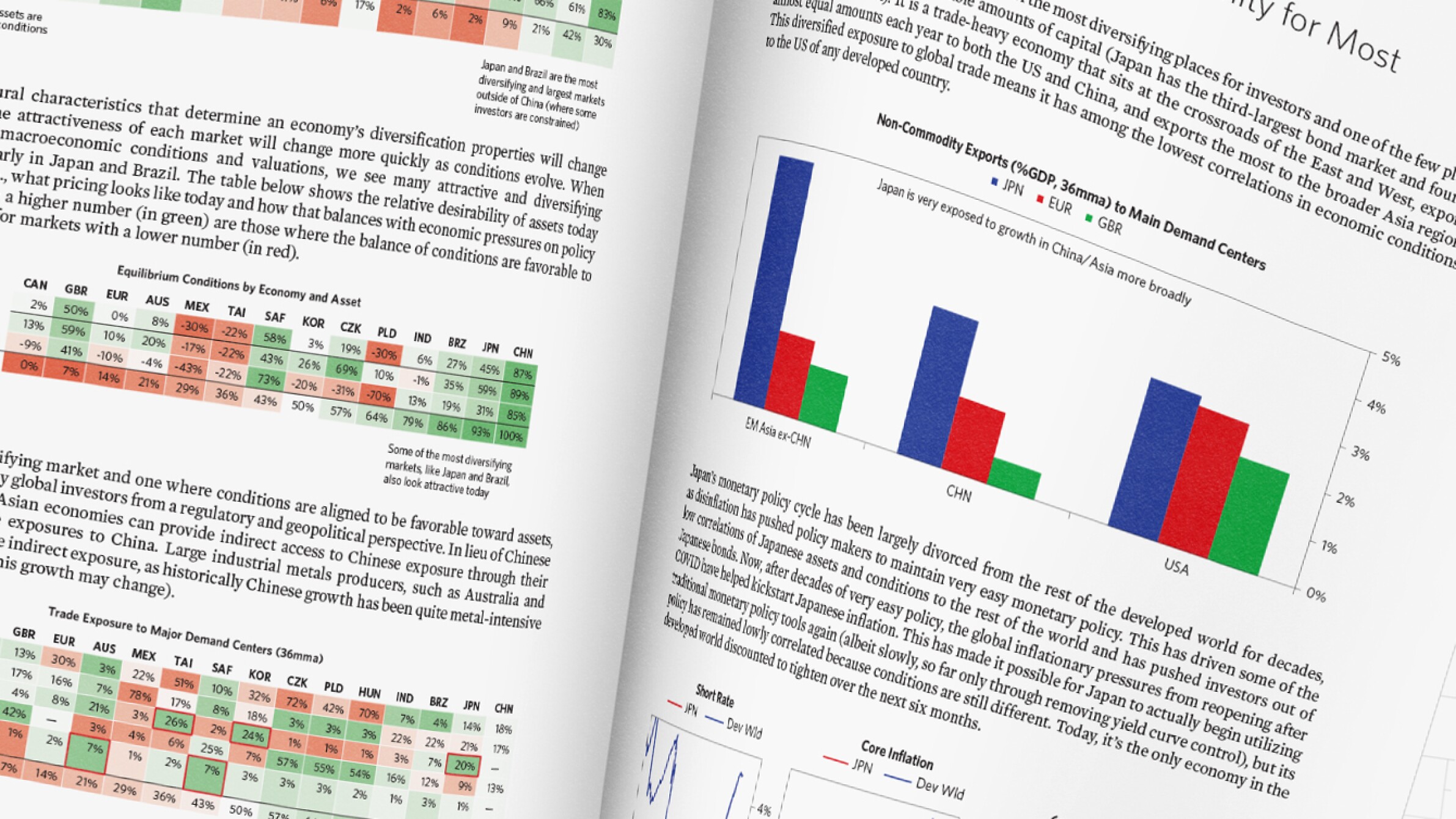

Below, we show a table that scans through the major global economies, ranking their asset markets by their value as a diversifier to a US-centric portfolio and their size (i.e., investability). The main takeaways are:

- Europe and the UK are the largest markets outside the US and typically make up investors’ largest allocations outside of US assets. But they are not highly diversifying because their conditions are so linked to the US.

- On the opposite side of the spectrum, Chinese assets are extremely diversifying because China has a relatively closed economy and is one of the largest demand centers in the world, leading to largely independent conditions and economic policy. But regulatory and geopolitical pressures have severely constrained most global investors’ exposure to China.

- Because exposure to China is constrained for some investors, Japan represents the largest opportunity for diversification today. It is a large market (the largest after Europe/UK), with listed companies that sell most of their products domestically, and has lowly correlated inflation and monetary policy.

- India and Brazil are the next most diversifying. Their conditions tend to be less linked to the US, but their market sizes are materially smaller than Japan, and this size difference doesn’t reflect the difficulties that many foreign investors face trying to access them (especially in India).

- There are a handful of diversifying but quite small emerging markets in Eastern Europe and Africa, which are more exposed to European growth or global commodity cycles than US conditions.

- Australia and medium-sized Asian economies—Korea, Taiwan—are less liquid and less diversifying than holding the largest Asian economies directly but meaningfully more diversifying than a European allocation. They have a lot more relative exposure to Chinese growth than most alternatives.

While these structural characteristics that determine an economy’s diversification properties will change slowly over time, the attractiveness of each market will change more quickly as conditions evolve. When we look at today’s macroeconomic conditions and valuations, we see many attractive and diversifying economies—particularly in Japan and Brazil. The table below shows the relative desirability of assets today across economies—i.e., what pricing looks like today and how that balances with economic pressures on policy makers. Markets with a higher number (in green) are those where the balance of conditions are favorable to assets, and vice versa for markets with a lower number (in red).

China is both a very diversifying market and one where conditions are aligned to be favorable toward assets, but it is challenging for many global investors from a regulatory and geopolitical perspective. In lieu of Chinese markets themselves, other Asian economies can provide indirect access to Chinese exposure through their large, non-commodity trade exposures to China. Large industrial metals producers, such as Australia and South Africa, can also provide indirect exposure, as historically Chinese growth has been quite metal-intensive (though the composition of this growth may change).

In the rest of this report, we walk through the most attractive markets for diversification in more detail.

Japan Presents the Largest Opportunity for Most Investors to Diversify

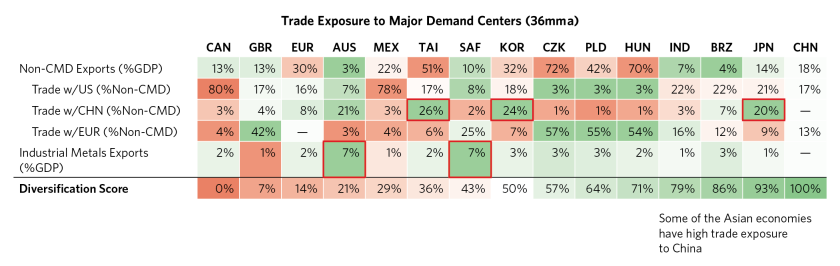

Outside of China, Japan stands out as one of the most diversifying places for investors and one of the few places in the world that can absorb sizable amounts of capital (Japan has the third-largest bond market and fourth-largest equity market). It is a trade-heavy economy that sits at the crossroads of the East and West, exports almost equal amounts each year to both the US and China, and exports the most to the broader Asia region. This diversified exposure to global trade means it has among the lowest correlations in economic conditions to the US of any developed country.

Japan’s monetary policy cycle has been largely divorced from the rest of the developed world for decades, as disinflation has pushed policy makers to maintain very easy monetary policy. This has driven some of the low correlations of Japanese assets and conditions to the rest of the world and has pushed investors out of Japanese bonds. Now, after decades of very easy policy, the global inflationary pressures from reopening after COVID have helped kickstart Japanese inflation. This has made it possible for Japan to actually begin utilizing traditional monetary policy tools again (albeit slowly, so far only through removing yield curve control), but its policy has remained lowly correlated because conditions are still different. Today, it’s the only economy in the developed world discounted to tighten over the next six months.

Not only are Japanese conditions lowly correlated to the US, but Japanese equities also provide a relatively high level of exposure to those domestic (versus global) conditions. While Japanese growth is driven by a diverse set of trade linkages, the majority of the sales for companies listed on Japanese exchanges are domestic—meaning the equity exposure is more diversifying than in a country like the UK (which is largely listing global corporations and thus has equity performance more levered to global growth). After decades of Japan basically not having a monetary policy cycle and relatively stagnant conditions, investors remain underweight Japanese assets.

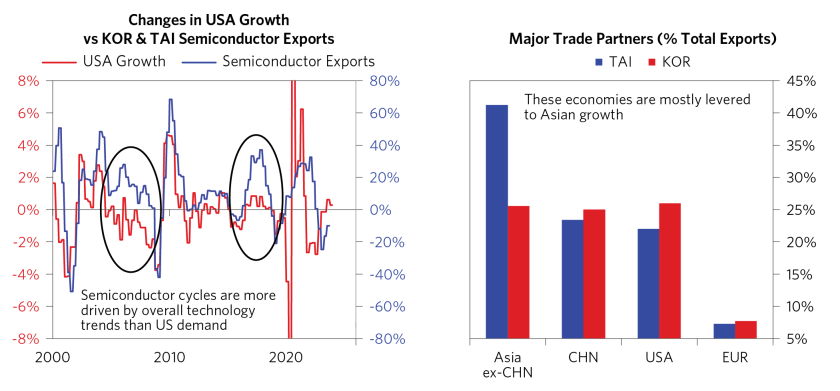

Smaller Asian Economies Have Diversifying Exposure to Technology and Chinese Growth

Korean and Taiwanese exposure to semiconductors and Asian growth helps make their assets diversifying relative to most other economies. Semiconductors are one of their main exports and make up a large portion of Korean and Taiwanese equity markets (Samsung represents 31% of the KOSPI 200, and TSMC 27% of the TAIEX). Semiconductors are critical to the functioning of the modern economy—for vehicle production, most technology products, and, increasingly, AI technology. And similar to other commodities, semiconductors have their own boom-bust cycles. It takes years for new supply to come online, leading prices to be quite volatile and sensitive to shifts in demand. Importantly, because semiconductors are so critical to every industry, the end markets for these products are quite diverse, and the semiconductor cycle is much less influenced by changes in US domestic demand than other non-commodity goods are. Korea and Taiwan in particular actually have more exposure to the Asia region overall than they do to the US through trade and provide another opportunity for investors to get more exposure to Chinese growth fluctuations.

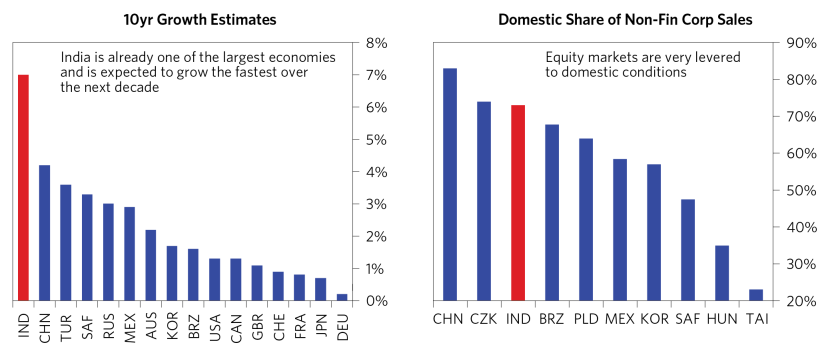

Indian Assets Provide Exposure to a Relatively Closed Economy

In some ways, India looks like China did two decades ago: it has a relatively closed economy, it’s one of the fastest-growing places in the world, and it is increasingly a destination for offshore investment. Foreign holdings of Indian assets remain quite small relative to other markets, meaning India is relatively immune to pressure from flighty capital. And it’s one of the largest service exporters with over 40% of its exports in services, predominantly in IT, which has been secularly growing as the technology sector expands. Services exports tend to be less subject to extreme drawdowns (like during the global financial crisis and COVID) and so can further insulate India from global growth slowdowns. These structural considerations are important because they mean that India is less whipsawed by changes in global growth and liquidity than many other EMs and that it also has more freedom to run monetary policy in line with domestic conditions. As a result, India’s growth and inflation have some of the lowest correlations to changes in US economic conditions across the world. As mentioned above, these markets are growing in size, but there are still some regulatory constraints for investors in India.

India is already one of the largest economies in the world and is one of the few places with strong demographic growth, driving it to be one of the fastest-growing countries in the world over the next decade. And when investors purchase Indian equities, they are really buying exposure to India’s large and growing domestic economy—almost 80% of corporate revenue comes from domestic sales.

Brazil Is the Most Liquid and Diversifying EM Market

Brazil is the largest emerging market outside of China, and its asset performance has been historically diversifying to investors because Brazil is a commodity exporter (unlike many of the other liquid EMs), has a robust and sizable domestic economy, and has strengthening external balances. Importantly, its growth is more leveraged to global commodity cycles (and to Chinese demand) than to US goods demand. Brazil exports a diverse set of commodities, such as soybeans, iron ore, and oil. And Brazil has a large and growing middle class, so, similar to India, many corporate sales occur domestically (almost 70%). Finally, Brazil has increasingly attracted stickier investments relative to portfolio inflows and loans, which are subject to squeeze pressures in the event of tightening global liquidity. As a result, it has become less vulnerable to global liquidity conditions, which allows it to run monetary policy more in accordance with domestic conditions.

Brazil tightened well in advance of developed world economies and has shifted to easing even as the developed world embarked on one of the most sizable tightening cycles of the last several decades. As you can see below, crisis periods such as 2008 certainly contributed to Brazil’s low correlation to US asset returns but are not the whole story—Brazilian assets have also outperformed during periods of US underperformance, particularly over this cycle.

Structurally, Many EMs Are Increasingly Insulated from US Policy

The structural shift underway in Brazil is also true across many EMs. These economies have historically been at the whim of the Fed, forced to tighten when the Fed does as tightening liquidity has driven currency pressure through increased borrowing costs and the pullback of global capital flows. Increasingly though, these economies are becoming more robust to external pressures—they’ve built up savings, encouraged the development of local currency markets, and attracted stickier capital. This robustness has allowed, and should continue to allow, emerging markets to run policy increasingly in line with their domestic conditions (like Brazil and many of the Central and Eastern European countries have done this cycle). While the diversification impacts of this shift will vary depending on an economy’s exposure, with those more leveraged to the US likely running policy more in sync with the US, on net this shift will likely support assets over the long term.

This research paper is prepared by and is the property of Bridgewater Associates, LP and is circulated for informational and educational purposes only. There is no consideration given to the specific investment needs, objectives, or tolerances of any of the recipients. Additionally, Bridgewater’s actual investment positions may, and often will, vary from its conclusions discussed herein based on any number of factors, such as client investment restrictions, portfolio rebalancing and transactions costs, among others. Recipients should consult their own advisors, including tax advisors, before making any investment decision. This material is for informational and educational purposes only and is not an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to buy the securities or other instruments mentioned. Any such offering will be made pursuant to a definitive offering memorandum. This material does not constitute a personal recommendation or take into account the particular investment objectives, financial situations, or needs of individual investors which are necessary considerations before making any investment decision. Investors should consider whether any advice or recommendation in this research is suitable for their particular circumstances and, where appropriate, seek professional advice, including legal, tax, accounting, investment, or other advice.

The information provided herein is not intended to provide a sufficient basis on which to make an investment decision and investment decisions should not be based on simulated, hypothetical, or illustrative information that have inherent limitations. Unlike an actual performance record simulated or hypothetical results do not represent actual trading or the actual costs of management and may have under or overcompensated for the impact of certain market risk factors. Bridgewater makes no representation that any account will or is likely to achieve returns similar to those shown. The price and value of the investments referred to in this research and the income therefrom may fluctuate. Every investment involves risk and in volatile or uncertain market conditions, significant variations in the value or return on that investment may occur. Investments in hedge funds are complex, speculative and carry a high degree of risk, including the risk of a complete loss of an investor’s entire investment. Past performance is not a guide to future performance, future returns are not guaranteed, and a complete loss of original capital may occur. Certain transactions, including those involving leverage, futures, options, and other derivatives, give rise to substantial risk and are not suitable for all investors. Fluctuations in exchange rates could have material adverse effects on the value or price of, or income derived from, certain investments.

Bridgewater research utilizes data and information from public, private, and internal sources, including data from actual Bridgewater trades. Sources include BCA, Bloomberg Finance L.P., Bond Radar, Candeal, Calderwood, CBRE, Inc., CEIC Data Company Ltd., Clarus Financial Technology, Conference Board of Canada, Consensus Economics Inc., Corelogic, Inc., Cornerstone Macro, Dealogic, DTCC Data Repository, Ecoanalitica, Empirical Research Partners, Entis (Axioma Qontigo), EPFR Global, ESG Book, Eurasia Group, Evercore ISI, FactSet Research Systems, The Financial Times Limited, FINRA, GaveKal Research Ltd., Global Financial Data, Inc., Harvard Business Review, Haver Analytics, Inc., Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS), The Investment Funds Institute of Canada, ICE Data, ICE Derived Data (UK), Investment Company Institute, International Institute of Finance, JP Morgan, JSTA Advisors, MarketAxess, Medley Global Advisors, Metals Focus Ltd, Moody’s ESG Solutions, MSCI, Inc., National Bureau of Economic Research, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Pensions & Investments Research Center, Refinitiv, Rhodium Group, RP Data, Rubinson Research, Rystad Energy, S&P Global Market Intelligence, Sentix Gmbh, Shanghai Wind Information, Sustainalytics, Swaps Monitor, Totem Macro, Tradeweb, United Nations, US Department of Commerce, Verisk Maplecroft, Visible Alpha, Wells Bay, Wind Financial Information LLC, Wood Mackenzie Limited, World Bureau of Metal Statistics, World Economic Forum, YieldBook. While we consider information from external sources to be reliable, we do not assume responsibility for its accuracy.

This information is not directed at or intended for distribution to or use by any person or entity located in any jurisdiction where such distribution, publication, availability, or use would be contrary to applicable law or regulation, or which would subject Bridgewater to any registration or licensing requirements within such jurisdiction. No part of this material may be (i) copied, photocopied, or duplicated in any form by any means or (ii) redistributed without the prior written consent of Bridgewater® Associates, LP.

The views expressed herein are solely those of Bridgewater as of the date of this report and are subject to change without notice. Bridgewater may have a significant financial interest in one or more of the positions and/or securities or derivatives discussed. Those responsible for preparing this report receive compensation based upon various factors, including, among other things, the quality of their work and firm revenues.