Link para o artigo original:https://www.bridgewater.com/research-and-insights/the-big-picture-back-to-the-future

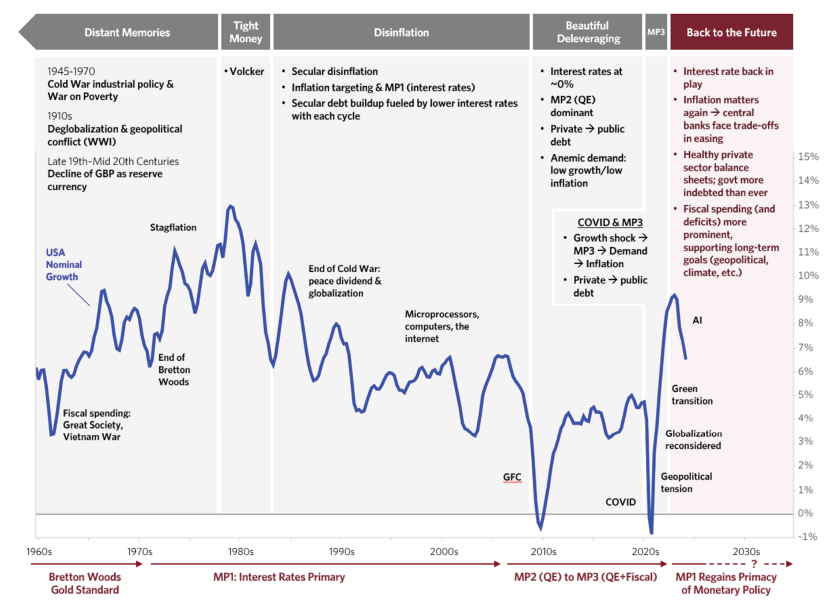

The secular investment landscape looks more like decades past than the last 20 years: the interest rate lever is back in play, inflation matters again, acute deleveraging is behind us, and the government is playing a more active economic role—all amid geopolitical tensions. At the same time, dynamics like AI and climate change are likely to shape the world in unprecedented ways.

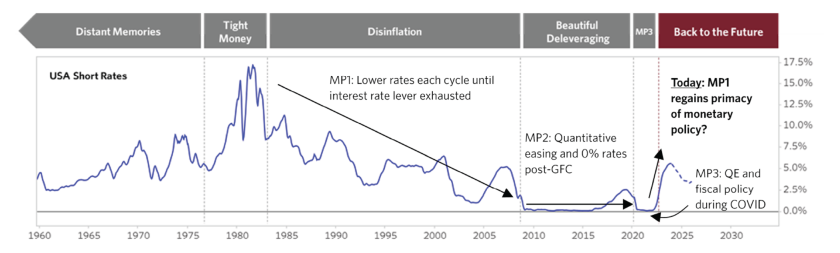

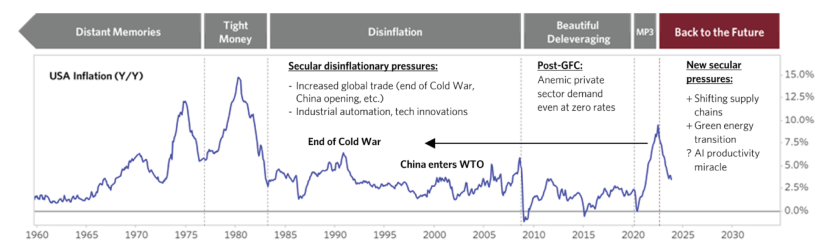

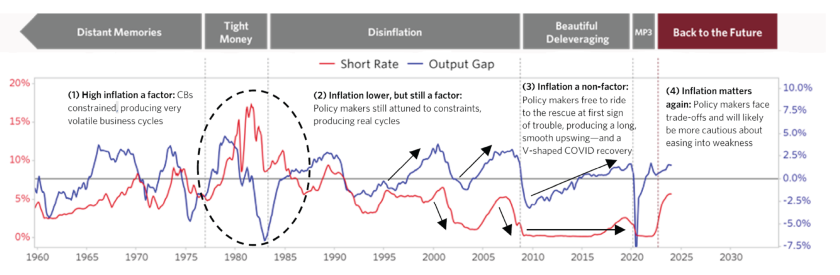

Over the course of a decade or more, investment performance and alpha opportunities will be driven by the broad characteristics of the environment. The ’70s had inflation; the period from the ’80s until recently had disinflation and steadily falling interest rates; and for over a decade following the financial crisis, we had abundant liquidity and near-zero interest rates. The most recent period reached its culmination with the deflationary impulse of the pandemic, which occurred at a time when near-zero interest rates called for coordinated monetary and fiscal stimulation, which overshot the mark and required tightening. The accumulation of these actions and outcomes has reset the landscape in ways that set the stage for the coming decade and beyond.

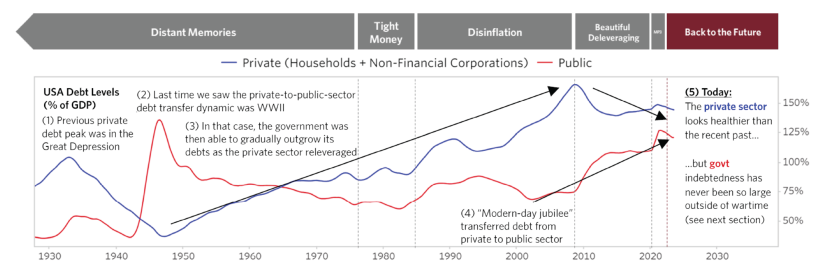

We believe we’ve entered a new era characterized by a number of drivers that haven’t been prominent in investors’ memories in many years. Interest rates have regained primacy as the most important lever of monetary policy, inflation is a feature of the economic landscape and creates trade-offs we haven’t experienced in decades, geopolitical tensions are creating new risks and leading to a reconsideration of how the economy is configured, and a healthier private sector has the balance sheet to leverage up under the right conditions, while the government is highly indebted and shifting to play a more direct role in the economy and markets than we’ve experienced in a long time. All of these create an impression of going “back to the future”—grappling with an investment landscape that contains distinct echoes of a more distant past. There are also a few characteristics of this era we’ve never experienced before: the public sector has never been so indebted during an expansion; climate change and AI are likely to shape the world in unprecedented ways; and China’s economy is likely to look very different than in recent decades, with ripple effects on the rest of the world.

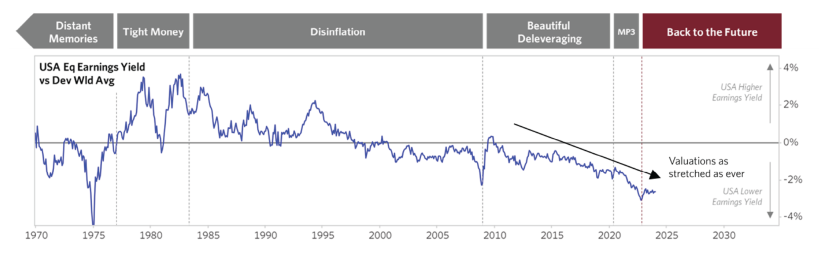

This backdrop will be of moderate importance month to month, but over the next decade, these characteristics will define the experience of investors in the new era. The era of abundant liquidity and zero rates that supported a massive run-up in risky assets is behind us. Higher rates reopen asset allocation possibilities that have been closed for years; at the same time, you don’t need to make a bold call about the future to be concerned that, as the drivers of the asset rally in the years following the financial crisis peter out, the prospects for asset performance are weakening. This new era calls for reconsidering asset allocation. But first, in this piece, we delve into defining the characteristics of our new era. Here, we focus primarily on US conditions, given the weight of US assets in investors’ portfolios and the importance of US monetary policy and liquidity to the world economy.

The Future Looks Like a Past That Feels Very Far Gone

The interest rate matters. It’s back in play as the primary lever of monetary policy to modulate the business cycle. For the first time in over a decade, money isn’t free. Interest rates aren’t zero; real rates aren’t negative. The interest rate underpins all other investment returns. After the global financial crisis, 0% rates made cash a “hot potato” and encouraged a move out the risk curve; now there’s a real hurdle for investments to clear to be profitable.

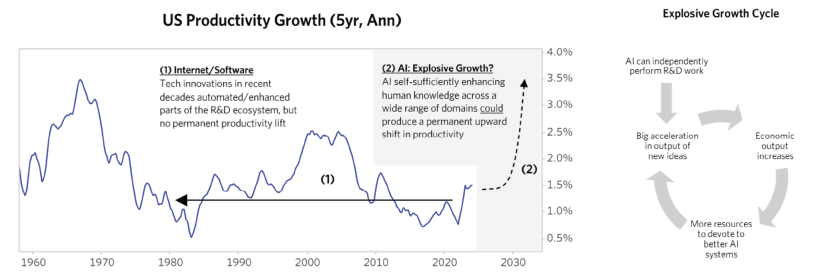

Inflation is no longer a “non-factor.” Even as acute inflation pressures have abated recently, the secular backdrop has shifted from disinflationary to more inflationary. After decades of rising globalization allowing them to tap into low-cost labor, businesses are investing in increasing resilience to geopolitical tensions by “double-doing” supply chains. Investments in curbing climate change and transitioning the world’s energy infrastructure—even if they save money longer-term by reducing damages over decades—are an inflationary source of spending in the coming years. Antitrust enforcement has increased, limiting corporate pricing power. More limited immigration and ongoing demographic shifts are tightening labor markets in many countries. The most meaningful deflationary force is the potentially transformative impact of AI. All in all, compared to the post-GFC era when 2% was about as high as inflation ever went, 2% now looks more likely to be a floor than a ceiling.

Monetary policy will likely be slower to ease and quicker to tighten, providing less of a floor for the economy and assets. After decades where any equity downturn was mild and short-lived because policy makers could step in and forcefully stimulate, policy makers once again face trade-offs in prioritizing supporting growth or keeping inflation at bay. When these trade-offs are more acute, swings in policy tend to be bigger, which is reflected in more volatile economic cycles and, in turn, more volatile asset price moves.

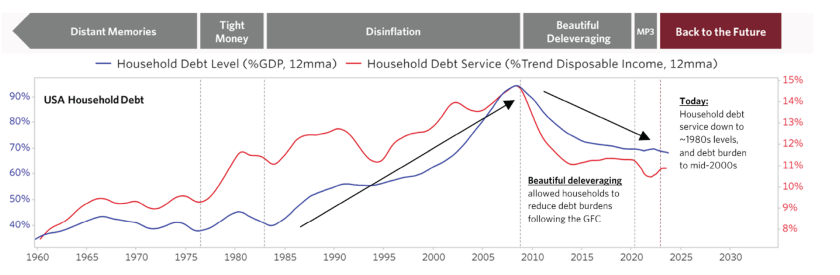

Acute deleveraging is behind us, and household balance sheets are as healthy as they have been in 20 years. For the first time in decades, there is room for households to leverage up in order to finance an expansion more rapid than their income growth.

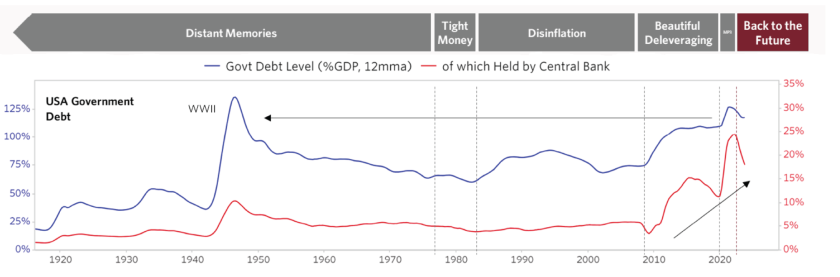

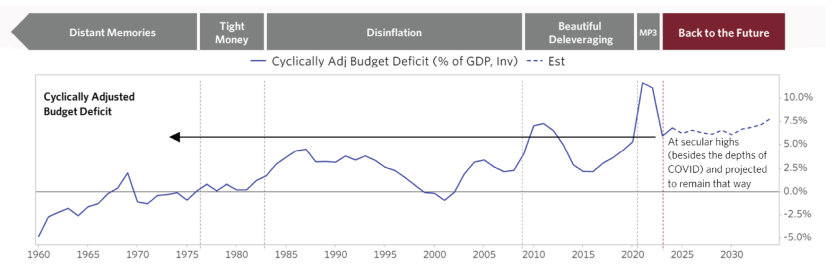

Deleveraging was relatively painless because the government offset it—and the government will continue playing a more active role in shaping the economy. Private sector deleveraging was made much less painful by the government’s deficit spending, which more than made up for the decline in private debt. As a result, the public sector is now as indebted as it has ever been.

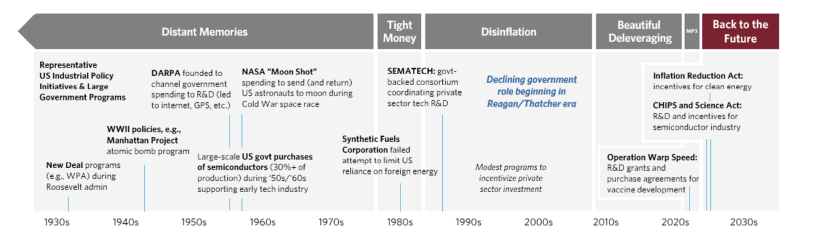

Government spending has played two distinct roles:

- a cyclical role, offsetting slowdowns with stimulation, most prominently during the COVID period, and

- a secular role, shaping the economy through industrial, regulatory, and fiscal policy in pursuit of geopolitical, energy, and other policy goals.

The cyclical role is currently behind us, but we suspect that it will remain incredibly tempting to use this lever again in future downturns given how effective it was during the COVID era. Sending consumers cash is a good way to guarantee rising spending. The secular role is not going anywhere because of the increasing understanding and perceived need for governments to play unique roles in addressing geopolitical challenges (e.g., incentives for semiconductor investments to address China concerns) and climate change (e.g., incentives for green energy).

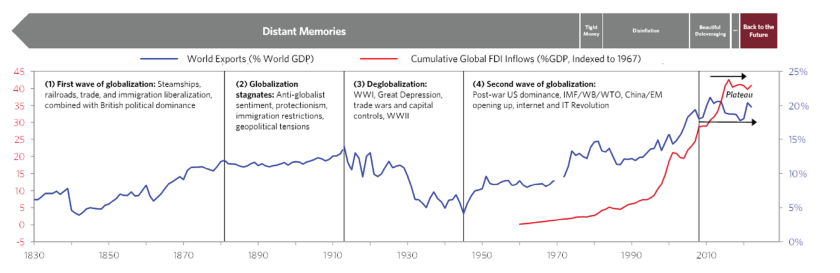

Secularly high geopolitical tensions underlie some of these dynamics. The flattening out of globalization eliminates a meaningful deflationary force and creates new inflationary pressures as companies and governments spend to control the resources they need and avoid reliance on potential adversaries. The closest historical analogue is the stagnation following the first wave of globalization as tensions built up into World War I and the near-cessation of world trade in the interwar era and during World War II. Ultimately, this took decades to reverse.

These dynamics are familiar to us from world economic history, but they’re relatively distant memories—at least 15 years for some of these elements and much longer for others.

At the Same Time, Some Elements of the Future Look Different Than Anything We’ve Experienced

Public sector indebtedness has never been so large outside of wartime and never so dependent on the Fed to fund it. And new debt continues to accumulate every day; the budget deficit is now as high as it’s ever been amid strong activity levels. In the next downturn (whenever it comes), the deterioration in government deficits will likely lead to a level of public sector funding needs larger than we’ve seen at any time other than the depths of COVID and wartime. So far, we have not seen any signs of the market being unwilling to finance these government debts—in contrast to the UK, for example, where in 2022 the Truss government’s aggressive fiscal plan spurred a spike in yields and a decline in the pound (this market-imposed fiscal discipline led to Truss’s immediate ouster and the scrapping of her government’s policies). But this could change and lead to additional constraints on policy, as well as pose a risk to the dollar.

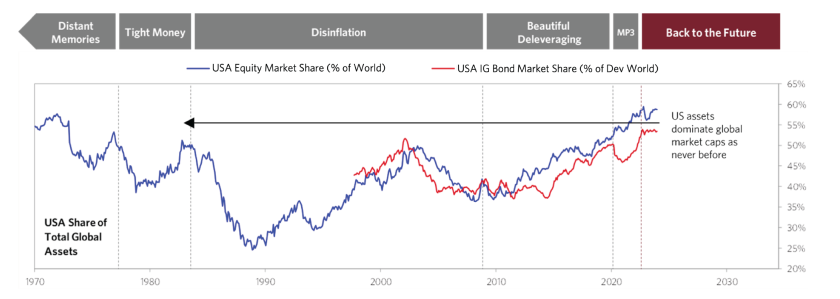

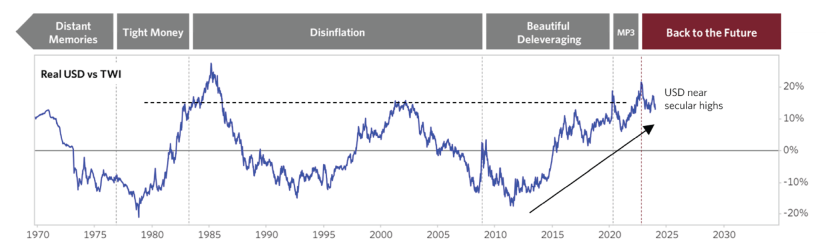

The US has a kind of “Dutch disease” from its financial assets. US assets are now the lion’s share of global asset markets. That, by default, makes the US a recipient of significant foreign inflows from savers. You can think of American financial assets almost like a “commodity”—one that savers need to park their money in. This leads to a special kind of “Dutch disease” akin to what economies experience when the world purchases their oil or other commodities. The dollar is secularly strong, and US assets have been less vulnerable to poor performance, with ample inflows to finance historically high government borrowing and continue pushing up relative equity valuations.

Climate risk is an unprecedented type of challenge. The economic changes that will unfold in the coming years present both physical and transition risks—from the physical damage caused by the effects of a changing climate to the difficulties involved in reconfiguring economies to pursue the required energy transition.

Increasingly large amounts of capital have been and will be spent on:

- Trying to mitigate climate change (e.g., minimizing temperature increases above 1.5°C by doing things like creating green energy to replace brown energy)

- Adapting to the changes that will take place as a result of climate change (e.g., building protections against rising sea levels and rising temperatures)

- Paying for the damages not prevented

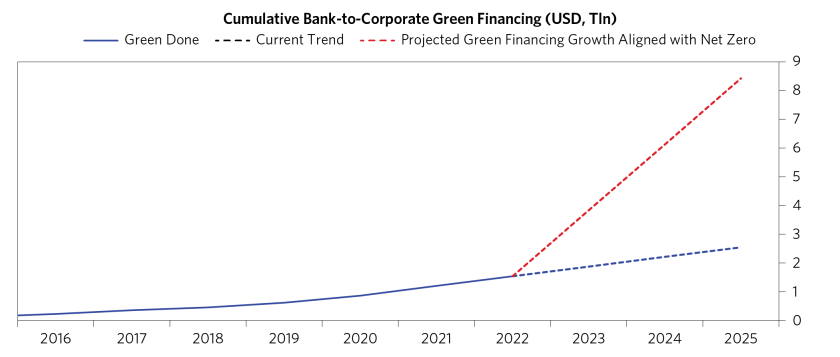

The physical damages of climate change are likely to be most immediately felt by hotter, low-lying, and agrarian economies, but they also pose substantial risks to major economies and markets—for example, rising costs of energy and climate adaptation for the highest-emitting sectors, challenges facing insurance, real estate liabilities, and many others. On the transition side, there is a wide range of possible pathways the transition might take, with policy makers around the world already responding to the challenge with a mix of stimulative and regulatory levers. Compared to the downward pressure on energy prices from the shale revolution of the past decade, investing to replace low-cost carbon energy sources is a structural upward pressure on inflation. While costs have come down for more established climate solutions (e.g., wind and solar), many other technologies (e.g., green hydrogen) are at earlier stages of maturity and depend on subsidies or government intervention to reach full commercial scale and unlock new sources of demand.

2023 was a key year in the energy transition: investment in renewables continued to grow, and it now surpasses investment in fossil fuels by a factor of 1.8, while policy makers at COP28 signed a commitment to “transition away” from fossil fuels. But the transition is still in its early innings. Only around 20% of companies in high-emitting sectors have taken credible steps to reduce their emissions, such as putting committed capex behind their reduction plans. And while substantial capital has been put toward the transition so far, the amount being invested falls well shy of what a successful transition would require—only one-sixth of the estimated amount of money that is required to keep the rise in temperatures to the targeted 1.5°C.

New AI/ML technologies have the potential to unleash a “productivity miracle” far beyond the industrial automation we have experienced in recent decades. The range of outcomes remains large, the timing uncertain, and the required investment significant. But it is worth considering the possibility that in the coming years, we could find ourselves in a world where a big share of white-collar work can be done at low or zero marginal cost, as discussed here. This would have enormous impacts across the economy—for example, on productivity, on gross margins, and on how spending and activity get reshuffled as new industries become economically viable and disposable income is freed up—producing dramatic winners and losers.

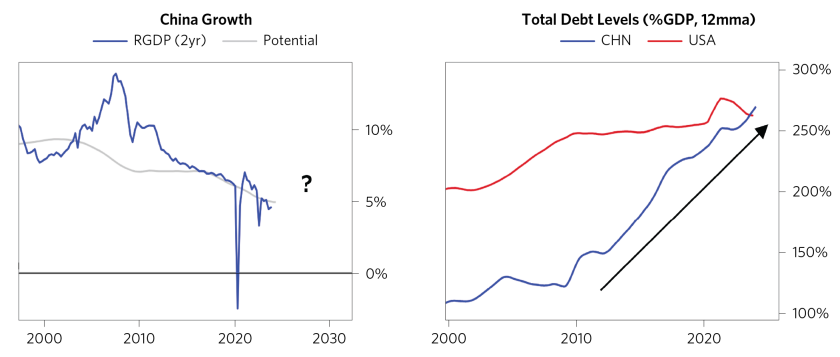

China’s economic circumstances have transformed, which will create a different ripple effect on the rest of the world than we have gotten used to. Looking back, the twin engines of China’s growth boom this century were 1) its ever-growing production of cheap goods sold to the rest of the world, which effectively exported deflation and 2) stimulus through debt-fueled, resource-intensive investment in property and infrastructure, which made China the dominant global source of demand for metals. Both of these forces have now shifted. The “labor arbitrage” that previously drove more and more production into China has now closed, removing this disinflationary impulse even for companies that aren’t part of the “deglobalization” wave. At the same time, the buildup of debt has left China needing to engineer a beautiful deleveraging and seeking to shift its growth model, such that it is likely to face a period of secularly slower growth. Globally, the biggest consequence is a new type of disinflationary impulse from lower commodity demand. Of course, much will depend on the mix of austerity versus stimulus that policy makers opt for as they try to engineer a beautiful deleveraging; so far, they have been relatively willing to tolerate weakness and cautious about overstimulating. Finally, another important force operating in the background will be the challenges presented by an aging population, an issue that is prevalent across the developed world as well but is particularly acute for China.

How Will This Environment Play Out for Investors?

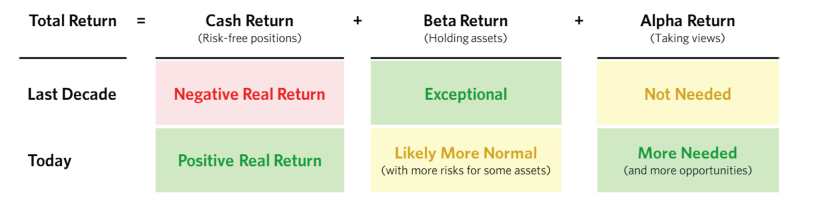

Day to day and month to month, investors face an overwhelming menu of different options for investment and look at performance and its drivers over shorter periods of time. But over a decade or so, investment performance is often determined by the broad characteristics of the environment.

Over the last decade, cash was “trash,” yielding a negative real return on your money. A confluence of favorable secular forces led to one of the best periods for beta in the last 60 years, as risky assets like stocks significantly outperformed holding cash. Exceptional beta returns meant that alpha often wasn’t required for investors to meet their goals. Looking ahead, the returns offered by cash and “risk-free” bonds look a lot more attractive, while the outlook for beta is more normal, with elevated risks for some assets and reasons to think tactical opportunities may be more valuable.

This research paper is prepared by and is the property of Bridgewater Associates, LP and is circulated for informational and educational purposes only. There is no consideration given to the specific investment needs, objectives, or tolerances of any of the recipients. Additionally, Bridgewater’s actual investment positions may, and often will, vary from its conclusions discussed herein based on any number of factors, such as client investment restrictions, portfolio rebalancing and transactions costs, among others. Recipients should consult their own advisors, including tax advisors, before making any investment decision. This material is for informational and educational purposes only and is not an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to buy the securities or other instruments mentioned. Any such offering will be made pursuant to a definitive offering memorandum. This material does not constitute a personal recommendation or take into account the particular investment objectives, financial situations, or needs of individual investors which are necessary considerations before making any investment decision. Investors should consider whether any advice or recommendation in this research is suitable for their particular circumstances and, where appropriate, seek professional advice, including legal, tax, accounting, investment, or other advice.

The information provided herein is not intended to provide a sufficient basis on which to make an investment decision and investment decisions should not be based on simulated, hypothetical, or illustrative information that have inherent limitations. Unlike an actual performance record simulated or hypothetical results do not represent actual trading or the actual costs of management and may have under or overcompensated for the impact of certain market risk factors. Bridgewater makes no representation that any account will or is likely to achieve returns similar to those shown. The price and value of the investments referred to in this research and the income therefrom may fluctuate. Every investment involves risk and in volatile or uncertain market conditions, significant variations in the value or return on that investment may occur. Investments in hedge funds are complex, speculative and carry a high degree of risk, including the risk of a complete loss of an investor’s entire investment. Past performance is not a guide to future performance, future returns are not guaranteed, and a complete loss of original capital may occur. Certain transactions, including those involving leverage, futures, options, and other derivatives, give rise to substantial risk and are not suitable for all investors. Fluctuations in exchange rates could have material adverse effects on the value or price of, or income derived from, certain investments.

Bridgewater research utilizes data and information from public, private, and internal sources, including data from actual Bridgewater trades. Sources include BCA, Bloomberg Finance L.P., Bond Radar, Candeal, Calderwood, CBRE, Inc., CEIC Data Company Ltd., Clarus Financial Technology, Conference Board of Canada, Consensus Economics Inc., Corelogic, Inc., Cornerstone Macro, Dealogic, DTCC Data Repository, Ecoanalitica, Empirical Research Partners, Entis (Axioma Qontigo), EPFR Global, ESG Book, Eurasia Group, Evercore ISI, FactSet Research Systems, The Financial Times Limited, FINRA, GaveKal Research Ltd., Global Financial Data, Inc., Harvard Business Review, Haver Analytics, Inc., Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS), The Investment Funds Institute of Canada, ICE Data, ICE Derived Data (UK), Investment Company Institute, International Institute of Finance, JP Morgan, JSTA Advisors, MarketAxess, Medley Global Advisors, Metals Focus Ltd, Moody’s ESG Solutions, MSCI, Inc., National Bureau of Economic Research, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Pensions & Investments Research Center, Refinitiv, Rhodium Group, RP Data, Rubinson Research, Rystad Energy, S&P Global Market Intelligence, Sentix Gmbh, Shanghai Wind Information, Sustainalytics, Swaps Monitor, Totem Macro, Tradeweb, United Nations, US Department of Commerce, Verisk Maplecroft, Visible Alpha, Wells Bay, Wind Financial Information LLC, Wood Mackenzie Limited, World Bureau of Metal Statistics, World Economic Forum, YieldBook. While we consider information from external sources to be reliable, we do not assume responsibility for its accuracy.

This information is not directed at or intended for distribution to or use by any person or entity located in any jurisdiction where such distribution, publication, availability, or use would be contrary to applicable law or regulation, or which would subject Bridgewater to any registration or licensing requirements within such jurisdiction. No part of this material may be (i) copied, photocopied, or duplicated in any form by any means or (ii) redistributed without the prior written consent of Bridgewater® Associates, LP.

The views expressed herein are solely those of Bridgewater as of the date of this report and are subject to change without notice. Bridgewater may have a significant financial interest in one or more of the positions and/or securities or derivatives discussed. Those responsible for preparing this report receive compensation based upon various factors, including, among other things, the quality of their work and firm revenues.