Link para o artigo original: https://www.bridgewater.com/research-and-insights/us-exceptionalism-drivers-of-equity-outperformance-and-whats-needed-for-a-repeat

Some of the largest drivers of US equity outperformance cannot be counted upon going forward. A lot depends on the ability of US tech to deliver and AI to unleash productivity across sectors.

We are coming off a decade of extraordinary US equity outperformance. An investment of $1 in the S&P 500 in 2010 is now worth more than $6, and the US has outperformed the rest of the world by several hundred percentage points over that period. In these Observations, we break down this S&P 500 outperformance into its key drivers to lay the foundation for the forward outlook.

- US equity outperformance has been driven by a combination of (a) faster revenue growth, (b) bigger margin expansion, and (c) rising P/E multiples—in roughly equal proportion. The returns for an unhedged global investor have been further juiced up by (d) the stronger US dollar over this window.

- The overarching forces behind many of these supports are the US having significantly better-run companies and a more favorable fiscal and policy backdrop:

- US companies are more innovative, more efficiently run, better at deploying capital, and have a more shareholder-friendly orientation than their developed world peers. This has manifested clearly in their generating a significantly higher return on invested capital (ROIC), which has allowed them to pay out a bigger share of their profits to shareholders without sacrificing revenue growth as well as to experience higher margins and multiple expansions.

- This was enabled and amplified by a more favorable pro-corporate environment in the US (bigger support from outsourcing, deregulation, lower taxes, etc.) along with a larger fiscal deficit at the macro level that allowed US corporate profit margins to surge as corporations were able to collect higher revenues from the household sector without paying correspondingly higher wages.

- While at a headline level, tech has had an outsize impact, from a sector composition perspective, this is not just a tech story. The US outperformance is broad-based across sectors and companies, as the factors noted above were true across the board. That said:

- Tech has punched well above its weight and accounts for more than half of the US outperformance versus developed world peers over the past decade. That mostly looks to be a more dominant manifestation of drivers just discussed. These companies are the best in the world at deploying capital and have also benefited disproportionately from this environment due to outsourcing, being recipients of the fiscal spending, and achieving unprecedented levels of concentration and dominance.

- The weight of the tech sector within the S&P 500 has grown from 20% to 40% over the past decade, as US business market share has shifted from less efficient corporations (like newspapers, brick and mortar stores, and onsite tech hardware vendors) to more efficiently run businesses (like online advertisers, e-commerce, and cloud providers) that are better at deploying capital and as a result also trade at a valuation premium. This rising share has also had a material impact on the rise in margins and P/E multiples for the aggregate index.

- On the other hand, major indices in Europe and the UK were hurt from lacking tech as well as from being overweight sectors like utilities and resources, which fared worse than the aggregate economy.

- The above dynamics led to higher realized returns for investors in US equities because this earnings outperformance was not priced in at the start of the decade. Over this period, US companies saw about twice as much multiple expansion as their peers, driven by a stronger upgrade to the longer-term earnings growth expectations as well as a bigger compression in equity risk premiums. It is typical, following a period of outperformance, for investors to pile in, chasing the winners and extrapolating past success.

- So today, strong US EPS growth outperformance is already reflected in the prices, at a time when many of the largest drivers of backward-looking US equity outperformance cannot be counted on to repeat going forward (from globalization to tax cuts to the massive fiscal support for profits). A lot now boils down to the ability of the US tech sector to deliver and AI to unleash a broad productivity impact across sectors. The bar for continued outperformance is high—but the potential is also there, as discussed by co-CIO Greg Jensen here and in yesterday’s videocast with GIC.

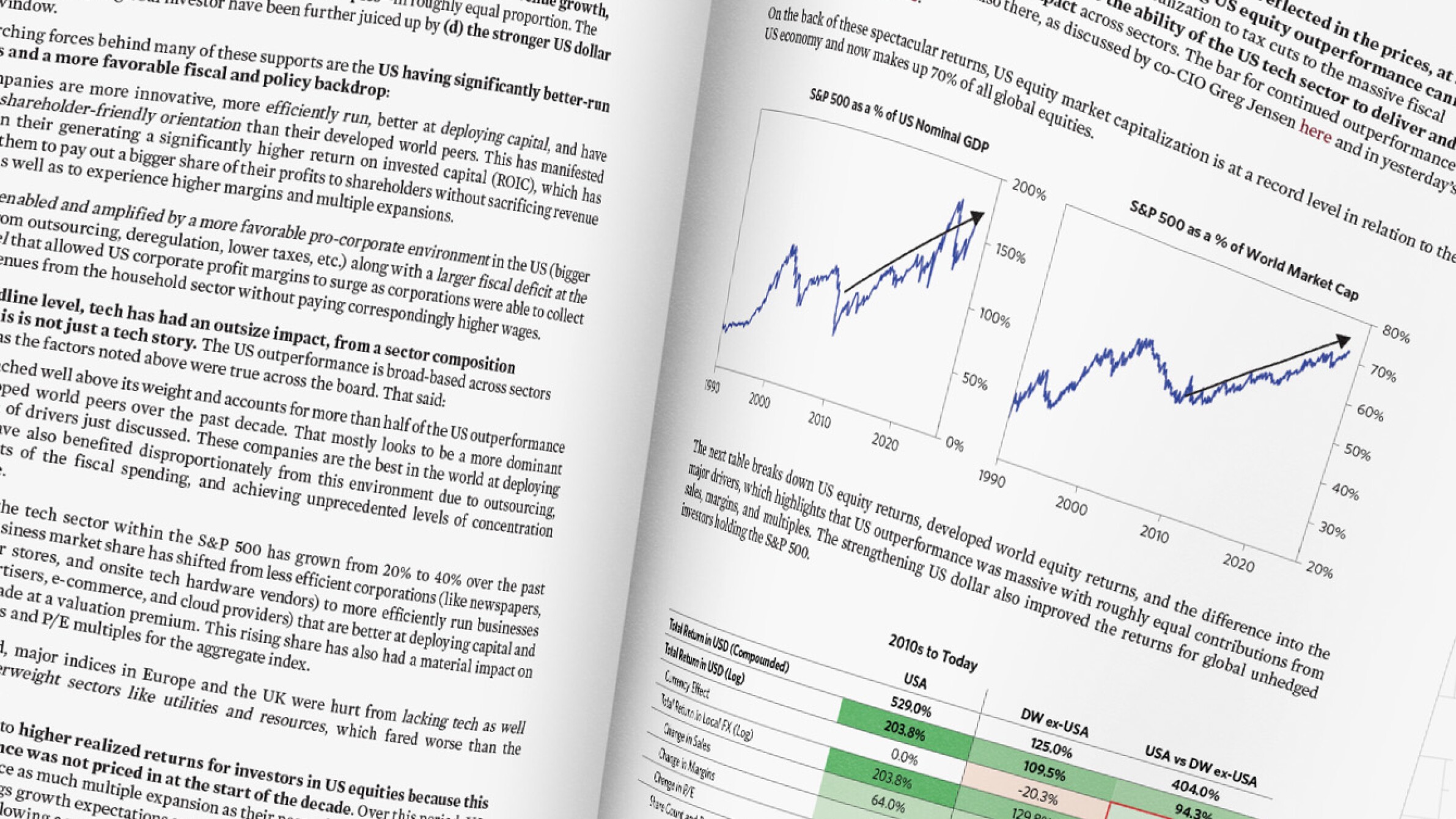

On the back of these spectacular returns, US equity market capitalization is at a record level in relation to the US economy and now makes up 70% of all global equities.

The next table breaks down US equity returns, developed world equity returns, and the difference into the major drivers, which highlights that US outperformance was massive with roughly equal contributions from sales, margins, and multiples. The strengthening US dollar also improved the returns for global unhedged investors holding the S&P 500.

Attributing US Equity Returns since 2010 in More Detail

Delving further into this attribution, the drivers are common to the tech as well non-tech sectors, and in many cases manifest in a bigger way for tech:

- While the technology sector has had an outsize impact, US outperformance has been broad across sectors. The US outperformances in sales and margin growth were roughly half due to the US tech sector and half due to other sectors, and the impact on P/E expansion was even higher for tech. But this is not just a tech story. In the table below, the last column demonstrates that even if the S&P 500 had no tech, it would still have outperformed meaningfully.

- Stronger sales growth was not just driven by US economic outperformance. While having a larger exposure to the US economy was a benefit for US companies, as shown below, there was less of a difference between the GDP growth rates facing companies in the US and elsewhere (revenue weighted NGDP growth row). This is because multinational companies domiciled around the world sell to many of the same customers globally. So, the revenue growth outperformance was more driven by US companies gaining market share. Being overweight tech was a sizable contributor to this, as US tech sector grew significantly faster than other sectors. Conversely, other countries were weighed down by being overweight sectors losing market share in the global economy, such as industrials and utilities.

- Stronger US margin growth was from a combination of more efficient capital deployment and a more favorable policy backdrop. US companies in aggregate captured a larger share of the economic pie, with profit margins especially supported by an expansionary fiscal policy. Trump tax cuts added about 7% to the S&P’s earnings. This is where having a larger exposure to the US economy especially benefited US companies.

- US companies saw about twice as much multiple expansion as their peers. This was from a combination of an up-revision in long-term cash flow expectations as well as compression in risk premiums. Once again, tech had an outsize impact.

- Faster net buybacks in the US were roughly offset by foreign companies paying higher dividends.

Next, we walk through some color behind these supports—profit margins, the role played by tech, the drivers of P/E expansion—and take a look at what’s priced in.

Profits

A big driver of the US outperformance has been the better profit growth from US companies. Over the past decade, the non-financials’ profit share of the total economy has risen to new highs in the US while falling to more normal levels elsewhere.

On top of a faster pace of revenue growth, US corporate profit margins have also expanded to new highs while companies outside the US have experienced flat—and lower—profit margins.

In terms of drivers, US companies in general are significantly more efficient in deploying capital.

The attributions mechanically highlight how US companies were able to grow their sales at a faster pace, saw better margin outcomes, and returned a larger amount of cash to shareholders: at the core of this is the fact that US companies deploy capital more efficiently. The measure below looks at the subsequent earnings generated per unit of capital deployed (across capex and acquisitions)—our version of “return on invested capital,” which suggests the clear advantage the US has enjoyed over time. This is a function of several variables, including higher innovation, more efficient operations, a more shareholder-friendly orientation as well as a more supportive pro-corporate environment.

We believe a much more active and dynamic shareholder-focused corporate culture is at the center of the decision-making process in the US. One example of this dynamism in the US is the degree of shareholder activism, which has historically shown a relationship with subsequent realized returns. We have seen other countries like Japan and Korea show more openness toward this recently, but on a level basis, they remain behind.

At the same time, the policy backdrop, including fiscal, was equally important.

From a macro perspective at the economy level, total saving across sectors needs to add up to total investment. Therefore, for corporate profits to rise, some other entity must dissave. The sector that has dissaved—i.e., borrowed—most in the US relative to other countries in recent years is the US government. The US government’s large deficits in recent years have been an important driver of why corporate profits could rise to a larger share of the overall economy. Fiscal deficits worked their way through the US economy to support corporate profits in numerous ways. For example, fiscal transfers to households more than offset the loss in private incomes during the COVID shock, allowing households to maintain their spending power despite falling private wages; as a result, US corporations were able to collect higher revenues from the household sector without paying correspondingly higher wages. The most direct channel of fiscal deficits supporting corporate profits was Trump’s corporate tax cuts.

Taking a step back, the panel below highlights the highly supportive backdrop that has allowed US corporate profit margins to expand and concentration to increase over the past several decades. Many of these are unlikely to be another leg of support over the coming years, and some could turn into a drag.

In summary, US corporate profitability has been supported by both (a) better capital deployment choices by a more competent and better-aligned management, and (b) operating in a more pro-corporate environment, including support from fiscal. Next, we briefly touch the role of tech in this outperformance.

While the Outperformance Is Broadly True, the Technology Sector Has Played an Outsize Role

In contribution terms, tech accounted for 54% of the total 74% US equity outperformance since 2010 versus the developed world. Of this, 22% can be attributed to the US index being overweight the tech sector relative to other countries, while 32% can be attributed to US tech radically outperforming global tech companies. So, the S&P 500 benefited from being overweight tech as well as US tech doing far better than what is classified as tech globally.

The tech sector’s total impact on the S&P 500 has been compounded by (a) sales growing faster than other sectors, (b) having significantly higher profit margins, and (c) trading at higher multiples. Tech has supported the S&P 500 across all channels (revenues, margins, and multiples).

The table below attributes margin growth at the sector level and is based on a bottom-up study done for the select period of 2007-18, when S&P 500 margins expanded a lot. As you can see, in the period of the most rapid pace of margin expansion for the S&P 500, rising earnings market share (even at flat margins) for the tech sector—which had a significantly higher level of profit margins—accounted for 10.1% of its 13.2% margins return impact and was in fact a much bigger deal than the organic margin expansion of companies within the tech sector. This is an example of how the share of output pie moving increasingly toward the more efficient tech sector has been a persistent tailwind for earnings and multiples for the aggregate S&P 500.

Closer Look at Returns Attribution for Mag 7

Each of the Mag 7 companies has its own story of exceptionalism. At a headline level, these companies generated annual returns in excess of 20%, twice that of the other S&P 500 companies. (Note that the returns shown in the table below are annualized.) A few things to call out:

- Most of the earnings outperformance for the individual Mag 7 companies came from their much faster sales growth while maintaining very high level of margins. Also, this was mostly not priced in, as the multiple compression over the window of rapid earnings growth was modest. (If it was mostly priced in, then we would have seen a significant portion of EPS growth accompanied by a reversion of P/Es).

- There were divergences across these Mag 7 companies. For example, Tesla saw the fastest sales and earnings growth, but from low levels, and some of this growth was diluted due to share issuance and was somewhat priced in (P/E reversion). On the other hand, unlike Tesla, Apple’s buybacks have been a support for its EPS. Finally, the AI champion Nvidia recently has seen a surge in sales and margins growth while maintaining a flat P/E ratio.

- This attribution further emphasizes how big a deal tech’s rapid sales share gains has been for the economy and index, allowing the S&P 500 to command higher margins and valuation multiples overall.

Multiples Expanded, Supporting Returns as Stronger Expectations Got Baked In

P/E multiples (or the inverse, equity earnings yields) have embedded in them (1) the effect of the discount rate, which discounts all future cash flows to the present; (2) long-term cash flow growth expectations, reflecting how much earnings are priced to grow in the future; and (3) the risk premium earned by investors for investing in a risky stock (instead of, for example, government bonds). The table below provides a rough attribution of the changes in P/E ratios across countries since 2010.

It is notable that US P/E ratios rose more than P/E ratios in other countries despite the relative rise in US bond yields over this window. Most of the outperformance boils down to the combination of stronger expectations for future long-term cash flows and compression in risk premiums. It is typical, following a period of outperformance, for investors to chase the winners and extrapolate past success. The fact that US companies delivered superior earnings and price performance over the past decade (which was most pronounced in tech) got priced in via these higher long-term cash flow expectations. This dynamic is what sets a higher hurdle for outperformance looking ahead.

Going Forward, the Hurdle for Continued US Outperformance Is High, and a Lot Depends on Technology

When considering the outlook for the S&P 500 from here, it is important to consider that many of the biggest drivers of the backward-looking returns discussed above (e.g., rising margins, rising P/E ratios, massive fiscal support to profits) are also what sets a high bar for outperformance looking ahead. And while the US continues to have significantly better companies, that’s also a lot more priced-in today versus a decade ago. The dotted lines below show what the EPS growth would need to be for equities to earn a normal 4% risk premium over bonds. As you can see, the expectations today for the US are significantly higher than a decade ago and relative to other equity markets.

Below, we show the EPS hurdle rate by sector needed to generate a normal level of risk premium for equity investors above the risk-free rate. You can see that US companies need about a 7% EPS growth to clear this hurdle, while other developed equity markets need less than half as much (3%) to achieve the same risk premium. This priced-in hurdle is broad-based across sectors, and with both a higher weight and more aggressive expectations, the burden for outperformance in tech and the Mag 7 specifically is higher than ever. In contrast, even with no earnings growth, Chinese companies should be able to generate a 4% risk premium over Chinese bonds—in other words, a very high risk premium is priced into Chinese stocks today.

And at a time when the hurdle is a lot higher, several of the backward-looking supports cannot be counted upon to provide another decade of strong support (from globalization to taxes to fiscal impulse). The next set of charts show how unlike at the start of the previous decade, today we are starting with elevated levels of margins, corporate share of profits, as well as multiples.

From here, a lot depends on technology—particularly if the AI revolution could create another leg of US equity outperformance. This matters directly for both (a) US Big Tech directly, which is now more than 30% of the index and has higher expectations as well as (b) how the AI/ML technology broadly unleashes productivity and how much of it gets captured as margins by companies across the various non-tech sectors. So, the bar is high—but continued outperformance is still a possibility. The potential for technology and AI was discussed in more depth in a recent report by co-CIO Greg Jensen.

This report is prepared by and is the property of Bridgewater Associates, LP and is circulated for informational and educational purposes only. There is no consideration given to the specific investment needs, objectives, or tolerances of any of the recipients. Additionally, Bridgewater’s actual investment positions may, and often will, vary from its conclusions discussed herein based on any number of factors, such as client investment restrictions, portfolio rebalancing and transactions costs, among others. Recipients should consult their own advisors, including tax advisors, before making any investment decision. This material is for informational and educational purposes only and is not an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to buy the securities or other instruments mentioned. Any such offering will be made pursuant to a definitive offering memorandum. This material does not constitute a personal recommendation or take into account the particular investment objectives, financial situations, or needs of individual investors which are necessary considerations before making any investment decision. Investors should consider whether any advice or recommendation in this research is suitable for their particular circumstances and, where appropriate, seek professional advice, including legal, tax, accounting, investment, or other advice. No discussion with respect to specific companies should be considered a recommendation to purchase or sell any particular investment. The companies discussed should not be taken to represent holdings in any Bridgewater strategy. It should not be assumed that any of the companies discussed were or will be profitable, or that recommendations made in the future will be profitable.

The information provided herein is not intended to provide a sufficient basis on which to make an investment decision and investment decisions should not be based on simulated, hypothetical, or illustrative information that have inherent limitations. Unlike an actual performance record simulated or hypothetical results do not represent actual trading or the actual costs of management and may have under or overcompensated for the impact of certain market risk factors. Bridgewater makes no representation that any account will or is likely to achieve returns similar to those shown. The price and value of the investments referred to in this research and the income therefrom may fluctuate. Every investment involves risk and in volatile or uncertain market conditions, significant variations in the value or return on that investment may occur. Investments in hedge funds are complex, speculative and carry a high degree of risk, including the risk of a complete loss of an investor’s entire investment. Past performance is not a guide to future performance, future returns are not guaranteed, and a complete loss of original capital may occur. Certain transactions, including those involving leverage, futures, options, and other derivatives, give rise to substantial risk and are not suitable for all investors. Fluctuations in exchange rates could have material adverse effects on the value or price of, or income derived from, certain investments.

Bridgewater research utilizes data and information from public, private, and internal sources, including data from actual Bridgewater trades. Sources include BCA, Bloomberg Finance L.P., Bond Radar, Candeal, CBRE, Inc., CEIC Data Company Ltd., China Bull Research, Clarus Financial Technology, CLS Processing Solutions, Conference Board of Canada, Consensus Economics Inc., DataYes Inc, DTCC Data Repository, Ecoanalitica, Empirical Research Partners, Entis (Axioma Qontigo Simcorp), EPFR Global, Eurasia Group, Evercore ISI, FactSet Research Systems, Fastmarkets Global Limited, The Financial Times Limited, FINRA, GaveKal Research Ltd., Global Financial Data, GlobalSource Partners, Harvard Business Review, Haver Analytics, Inc., Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS), The Investment Funds Institute of Canada, ICE Derived Data (UK), Investment Company Institute, International Institute of Finance, JP Morgan, JSTA Advisors, LSEG Data and Analytics, MarketAxess, Medley Global Advisors (Energy Aspects Corp), Metals Focus Ltd, MSCI, Inc., National Bureau of Economic Research, Neudata, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Pensions & Investments Research Center, Pitchbook, Rhodium Group, RP Data, Rubinson Research, Rystad Energy, S&P Global Market Intelligence, Scientific Infra/EDHEC, Sentix GmbH, Shanghai Metals Market, Shanghai Wind Information, Smart Insider Ltd., Sustainalytics, Swaps Monitor, Tradeweb, United Nations, US Department of Commerce, Verisk Maplecroft, Visible Alpha, Wells Bay, Wind Financial Information LLC, With Intelligence, Wood Mackenzie Limited, World Bureau of Metal Statistics, World Economic Forum, and YieldBook. While we consider information from external sources to be reliable, we do not assume responsibility for its accuracy.

This information is not directed at or intended for distribution to or use by any person or entity located in any jurisdiction where such distribution, publication, availability, or use would be contrary to applicable law or regulation, or which would subject Bridgewater to any registration or licensing requirements within such jurisdiction. No part of this material may be (i) copied, photocopied, or duplicated in any form by any means or (ii) redistributed without the prior written consent of Bridgewater® Associates, LP.

The views expressed herein are solely those of Bridgewater as of the date of this report and are subject to change without notice. Bridgewater may have a significant financial interest in one or more of the positions and/or securities or derivatives discussed. Those responsible for preparing this report receive compensation based upon various factors, including, among other things, the quality of their work and firm revenues.