Link para o artigo original: https://www.bridgewater.com/research-and-insights/our-thoughts-on-large-us-deficits-and-their-impact-on-bond-yields

Following Trump’s victory, we assess the supply/demand picture for US debt, and what it means for yields going forward.

As government deficits have risen, both in the US and globally, the impact of government borrowing on bond yields has become an increasingly important topic for investors. Since Trump’s election win, we have seen even more interest in this question because the Trump administration is widely seen as likely to increase or maintain high fiscal deficits.

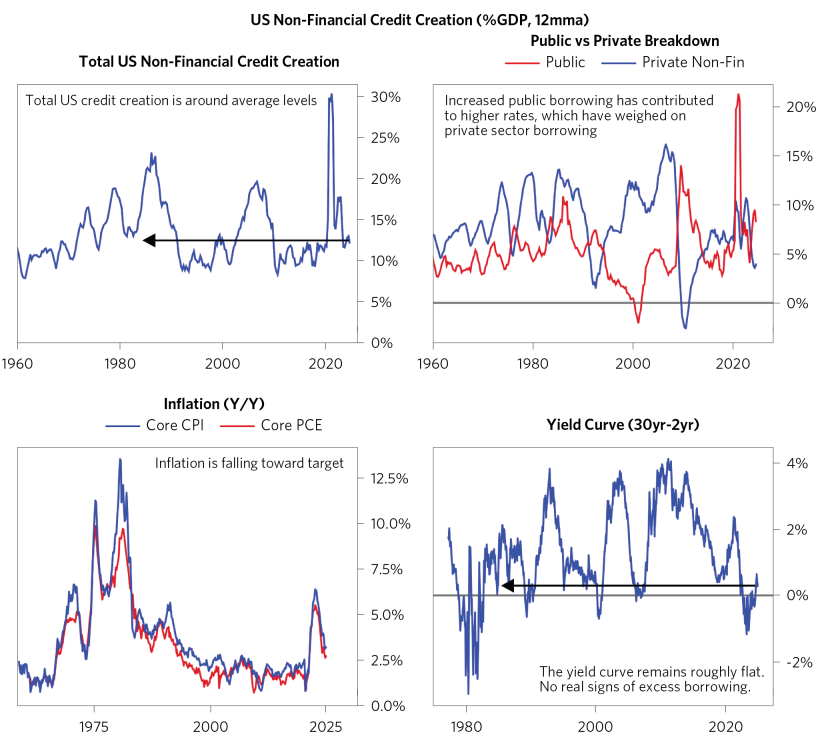

To assess the impact of large deficits on yields, it is important to look at the total debt in the economy, not just government debt. This is because public and private debt (both as an asset and as a source of spending) are reasonably fungible, so what matters for markets and the economy is how much collective new credit is being created, and the incentive and desire of investors to buy it.

In terms of how total borrowing flows through to rates, there is an economic pressure and a pressure created by supply and demand for debt. If there is too much borrowing and spending, leading to inflation, the central bank will raise rates, which in turn will curtail private sector borrowing. And if there is too much aggregate borrowing relative to demand, rates will rise as investors require a higher premium for lending out their marginal dollar. If government spending gets high enough, it can lead to real debt problems and sharply higher bond yields because a) the government doesn’t really get squeezed out (at least not in a timely way) by higher borrowing costs and b) there are limits to how much private sector borrowing can decline to offset higher government borrowing.

That doesn’t look like where we are now or where we are headed—markets look like they are reflecting more of a balanced supply/demand picture than an excess of borrowing, inclusive of public and private. Some of the danger signs to watch for are rates rising led by the long end, total debt levels as a share of the economy rising, and currency weakness. The curve steepening driven by the long end is usually a sign you may have a problem finding buyers, and as you can see below, that is not the case today.

Before going into the details, the charts below highlight that, despite higher government deficits, total borrowing is about average. High public borrowing has contributed to the need for higher rates, which have depressed private sector borrowing. This return to normal levels of credit creation has helped gradually drive inflation down toward target. And in terms of supply and demand for debt, the risk premiums on the long end look about average, with no market signs that economic or debt limits are currently being hit. This contrasts with other times when abnormally high total borrowing has driven yields and risk premiums up (via higher supply, higher inflation, or both), such as during the 1980s, the GFC, or the height of COVID.

As noted above, duration is one of the more globally fungible markets, so looking at the total borrowing across the developed world is relevant. There, total borrowing is roughly average for when the economy is healthy, while government borrowing is at highs normally only seen in recessions.

On a Level Basis, Total Debt in the Developed World, Even in the US, Is Flat or Falling

These borrowing levels are instructive as to why risk premiums on borrowing are not currently high. As the charts below show, across many developed world economies, total debts relative to GDP are falling rather than rising. And notably, the amount of debt that needed to be taken down (exclusive of central bank purchases) has come down—though more recently, central bank selling adds a bit. Pressure is put on markets and economies when debt and spending rise faster than what the economy can produce. Across much of the developed world, debt levels peaked in the global financial crisis, a crisis brought on by too much private sector borrowing relative to what the economy could handle. There was, of course, a massive increase in money and credit in response to COVID that pushed the level of debt higher in the short term, but more recently, the path of stability/lower debts has resumed.

Today, as we showed above, the picture is flipped, with much more public sector borrowing than private. This equilibrium is not a problem as it relates to markets but has led, and may continue to lead, to political issues the longer the private sector is priced out of debt markets by the public sector. There seems to be more concern today about how much borrowing is too much for the public sector when, in aggregate, the overall borrowing relative to the size of the economy is declining across the developed world.

The Base Case for Supply Is More of the Same: High Fiscal Deficits and Low Private Borrowing

Starting with supply, as we showed above, the total borrowing that needs to be taken down is not all that high relative to normal. In the US, with the new administration likely pushing to extend the Trump tax cuts but not expand government spending much beyond the level it is today, public sector issuance is likely to remain roughly constant if not rise a bit to somewhere in the range of 7-8% of GDP. And in terms of the total supply of Treasury debt that needs to be taken down, less quantitative tightening from the Fed is likely to be an offset to marginally higher deficits. However, in aggregate, this remains a high level of government borrowing, which is being cleared by higher yields that have kept down private sector borrowing.

If the Trump administration really pushes to the point where the private sector can’t be depressed enough to offset the higher deficit, then we will start to get problems. But we do see constraints on fiscal spending—inflation remains a constraint on policy makers, particularly after the impact it had on the last campaign. And there is not much appetite, even from Republicans, for much higher deficits. The chart below is meant to illustrate the range of outcomes in the next few years rather than our estimate of what will occur. The black line in the left-hand chart below shows what the baseline of current law would produce if the current tax regime were not rolled, and the red line is what President Trump’s proposals would look like if they were enacted in reasonably full measure.

Private sector borrowing has been depressed by much higher yields, but it saw a small pickup with the drop in yields earlier this year. That looks to be turning as yields have risen. Depressed private sector borrowing has been an important part of getting to equilibrium, but now that it is already at low levels, it is unlikely to fall a lot further. The current level of private sector borrowing has not been lower than it is today, with the exception of pretty severe downturns.

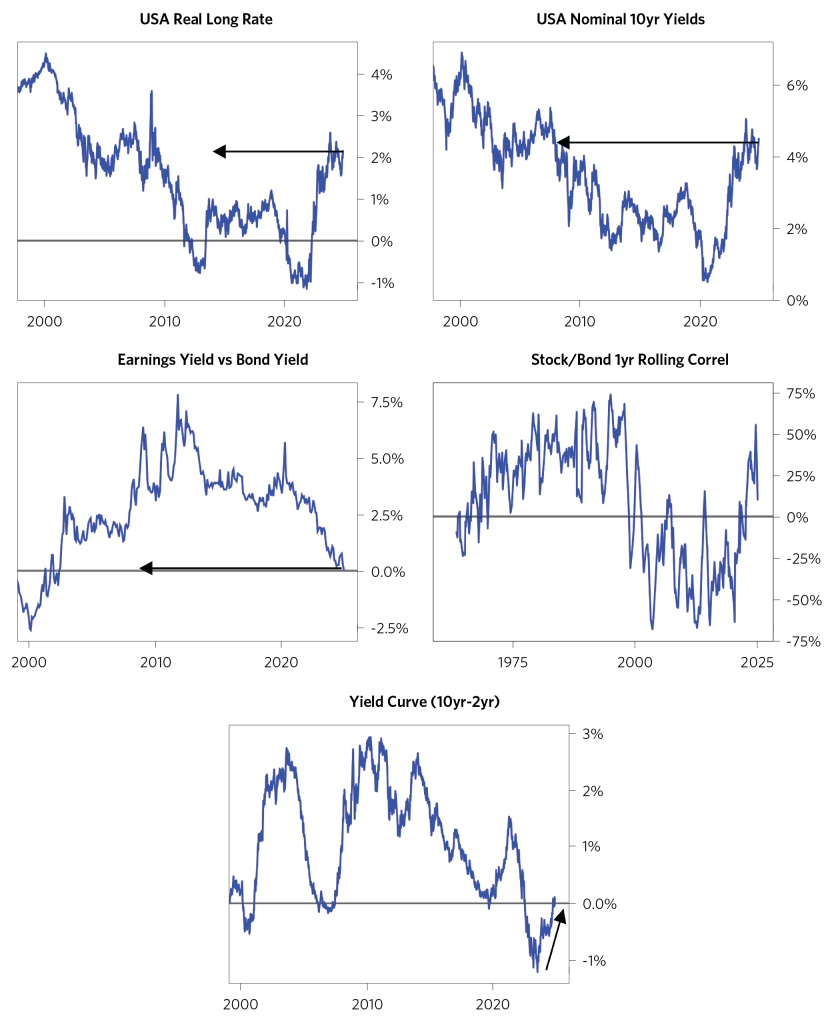

The Incentive to Buy Bonds Has Improved, Supporting Demand, Particularly from Real Money Investors

On the demand side, the incentive to buy bonds is higher than it has been. We see the appetite for bonds as supported by our view that unlevered investors generally remain under-allocated to bonds relative to longer-term targets, and bonds are more diversifying for an equity-heavy portfolio at these higher yields. The yield for unlevered investors, both real and nominal, is much higher than it has been for many years. At the same time, as US equity markets have risen, earnings yields have fallen to the point that they are now roughly equal to bond yields. Real yields are now at 2% in the US—a level that, before late last year, hadn’t been seen since the mid-2000s—and high relative to much of the rest of the developed world. US nominal yields are at levels where the yield is attractive and diversifying relative to stocks in any growth slowdown. Though the yield curve, which matters for levered investors, is relatively flat, it is steepening and may steepen further if the Fed continues to ease. Banks have not been buying many bonds and are likely to step in more if the curve steepens and/or regulations are eased to enable more lending.

Bond market pricing looks consistent with pretty high and stable government borrowing, pretty low and stable private sector borrowing, and not much pressure on risk premiums. Market pricing of the Fed’s terminal rate has come in substantially over the past six weeks, and the Fed is no longer priced to bring rates down to its definition of neutral. With yields near cyclical highs and markets discounting that the terminal policy rate will remain in restrictive territory, markets are signaling that the economy is strong and the Fed doesn’t need to generate a credit response. Most of the sell-off in long rates since September has come through real yields, while 10-year breakevens have remained relatively stable (ticking up only modestly). Breakeven inflation remaining around target is consistent with markets pricing a continually subdued private sector. Though markets are discounting some bounce in near-term inflation, much of that can be chalked up to the Trump administration’s tariffs rather than markets discounting a sustainably higher level of inflation.

This research paper is prepared by and is the property of Bridgewater Associates, LP and is circulated for informational and educational purposes only. There is no consideration given to the specific investment needs, objectives, or tolerances of any of the recipients. Additionally, Bridgewater’s actual investment positions may, and often will, vary from its conclusions discussed herein based on any number of factors, such as client investment restrictions, portfolio rebalancing and transactions costs, among others. Recipients should consult their own advisors, including tax advisors, before making any investment decision. This material is for informational and educational purposes only and is not an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to buy the securities or other instruments mentioned. Any such offering will be made pursuant to a definitive offering memorandum. This material does not constitute a personal recommendation or take into account the particular investment objectives, financial situations, or needs of individual investors which are necessary considerations before making any investment decision. Investors should consider whether any advice or recommendation in this research is suitable for their particular circumstances and, where appropriate, seek professional advice, including legal, tax, accounting, investment, or other advice. No discussion with respect to specific companies should be considered a recommendation to purchase or sell any particular investment. The companies discussed should not be taken to represent holdings in any Bridgewater strategy. It should not be assumed that any of the companies discussed were or will be profitable, or that recommendations made in the future will be profitable.

The information provided herein is not intended to provide a sufficient basis on which to make an investment decision and investment decisions should not be based on simulated, hypothetical, or illustrative information that have inherent limitations. Unlike an actual performance record simulated or hypothetical results do not represent actual trading or the actual costs of management and may have under or overcompensated for the impact of certain market risk factors. Bridgewater makes no representation that any account will or is likely to achieve returns similar to those shown. The price and value of the investments referred to in this research and the income therefrom may fluctuate. Every investment involves risk and in volatile or uncertain market conditions, significant variations in the value or return on that investment may occur. Investments in hedge funds are complex, speculative and carry a high degree of risk, including the risk of a complete loss of an investor’s entire investment. Past performance is not a guide to future performance, future returns are not guaranteed, and a complete loss of original capital may occur. Certain transactions, including those involving leverage, futures, options, and other derivatives, give rise to substantial risk and are not suitable for all investors. Fluctuations in exchange rates could have material adverse effects on the value or price of, or income derived from, certain investments.

Bridgewater research utilizes data and information from public, private, and internal sources, including data from actual Bridgewater trades. Sources include BCA, Bloomberg Finance L.P., Bond Radar, Candeal, CBRE, Inc., CEIC Data Company Ltd., China Bull Research, Clarus Financial Technology, CLS Processing Solutions, Conference Board of Canada, Consensus Economics Inc., DataYes Inc., DTCC Data Repository, Ecoanalitica, Empirical Research Partners, Entis (Axioma Qontigo Simcorp), EPFR Global, Eurasia Group, Evercore ISI, FactSet Research Systems, Fastmarkets Global Limited, The Financial Times Limited, FINRA, GaveKal Research Ltd., Global Financial Data, GlobalSource Partners, Harvard Business Review, Haver Analytics, Inc., Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS), The Investment Funds Institute of Canada, ICE Derived Data (UK), Investment Company Institute, International Institute of Finance, JP Morgan, JSTA Advisors, LSEG Data and Analytics, MarketAxess, Medley Global Advisors (Energy Aspects Corp), Metals Focus Ltd, MSCI, Inc., National Bureau of Economic Research, Neudata, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Pensions & Investments Research Center, Pitchbook, Rhodium Group, RP Data, Rubinson Research, Rystad Energy, S&P Global Market Intelligence, Scientific Infra/EDHEC, Sentix GmbH, Shanghai Metals Market, Shanghai Wind Information, Smart Insider Ltd., Sustainalytics, Swaps Monitor, Tradeweb, United Nations, US Department of Commerce, Verisk Maplecroft, Visible Alpha, Wells Bay, Wind Financial Information LLC, With Intelligence, Wood Mackenzie Limited, World Bureau of Metal Statistics, World Economic Forum, and YieldBook. While we consider information from external sources to be reliable, we do not assume responsibility for its accuracy.

This information is not directed at or intended for distribution to or use by any person or entity located in any jurisdiction where such distribution, publication, availability, or use would be contrary to applicable law or regulation, or which would subject Bridgewater to any registration or licensing requirements within such jurisdiction. No part of this material may be (i) copied, photocopied, or duplicated in any form by any means or (ii) redistributed without the prior written consent of Bridgewater® Associates, LP.

The views expressed herein are solely those of Bridgewater as of the date of this report and are subject to change without notice. Bridgewater may have a significant financial interest in one or more of the positions and/or securities or derivatives discussed. Those responsible for preparing this report receive compensation based upon various factors, including, among other things, the quality of their work and firm revenues.