Link para o artigo original: https://www.bridgewater.com/research-and-insights/most-global-economies-remain-in-disequilibrium-requiring-policy-action

Despite a year’s worth of monetary tightening, most major economies remain in disequilibrium. This is not unusual, as restoring equilibrium often takes a series of moves over time. The implications for policy and markets remain material.

We have received questions about our work on equilibriums, what we mean by that, the relevance to policy and to markets, and how those conditions differ across economies. In brief, we believe that there are three major equilibriums and two major policy levers that interact to drive markets and economies:

- Spending in line with output, which is in line with capacity

- Incomes in line with debts

- Normal risk premiums across assets

If these conditions don’t exist, intolerable circumstances will ensue that will drive changes toward these equilibriums being reached. For example, if an economy’s usage of capacity (e.g., labor and capital) remains low for an extended period of time, that will lead to social and political problems as well as business losses, which will produce further changes until these equilibriums are reached.

The two levers are monetary policy and fiscal policy. Monetary policy is managed by central banks to drive money and credit changes that finance the purchases of goods, services, and financial assets. Fiscal policy is managed by the legislative and executive branches of governments to use taxes, government spending, and laws and regulations to influence economic behavior. Structural reforms are changes in laws and regulations, so they occur via fiscal policies. All the economic and market swings that we see reflect the never-ending struggles of the marketplace and of policy makers (using these levers) to bring these equilibriums about.

The things that you look at to assess these conditions are fairly common sense. Is the unemployment rate neither too high nor too low, growth roughly equal to potential, and the level of nominal spending about right to have an inflation rate that is neither too high nor too low? Is the current inflation rate about right, and are interest rates roughly discounting that level of inflation plus a normal real yield? Is the level of spending growth in line with incomes, or is there a leveraging up or big credit contraction going on? If you look at the current and discounted future yield on cash, are bonds offering a normal risk premium relative to that, and are equities offering a normal risk premium relative to bonds? If so, the flow of capital is likely to be more orderly and more supportive to sustainable economic conditions.

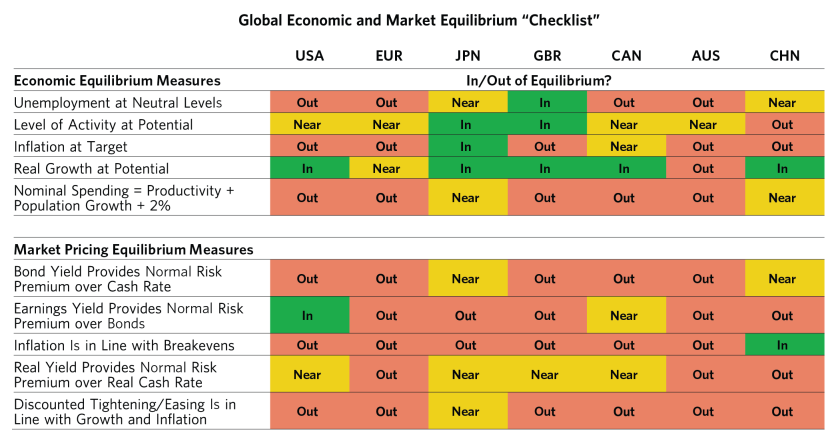

If things are about right, monetary and fiscal policy can be more moderate and gradual. The further out of line they are, the more aggressive the policy response must be to bring conditions back toward equilibrium. The following table summarizes a number of these measures and where things stand by economy.

Once an economy is out of equilibrium, there are multiple paths to guide it back, which unfold over a number of months or years as a function of the decisions of policy makers. For example, the entire world experienced a disinflationary disequilibrium via the pandemic. Policy makers in each economy pulled their fiscal and monetary levers differently, which led some economies (the US, Europe, the UK) to experience an inflationary overshoot, while others (China) are experiencing a disinflationary undershoot. Now, those differences in conditions call for different pulls of the next lever. The sequence of actions and their impacts over time will determine each economy’s path to equilibrium.

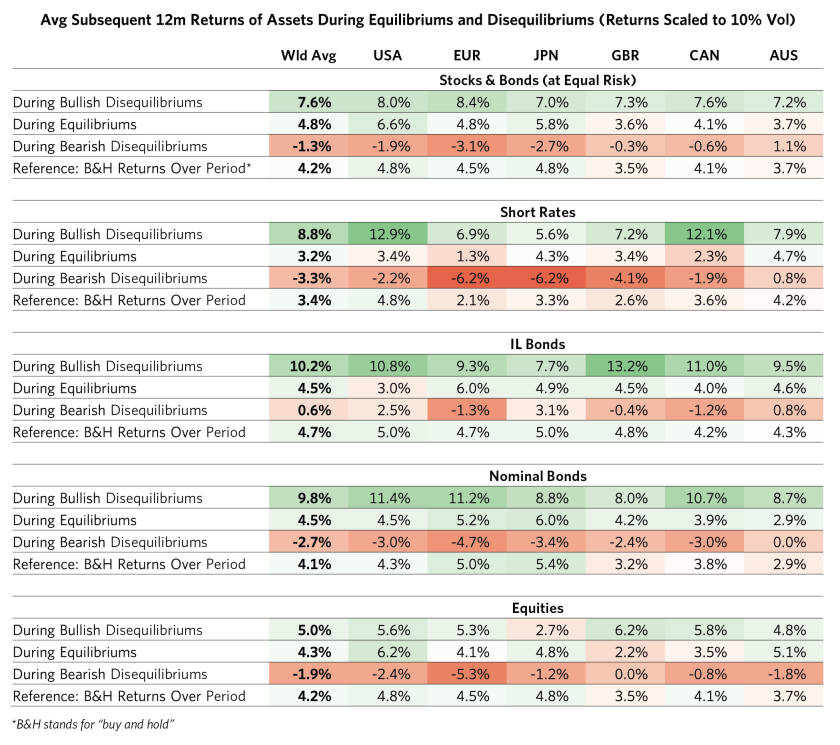

The path to equilibrium has impacts on markets. For example, disequilibriums that call for stimulation and associated expansions of liquidity, interest rate cuts, and fiscal support tend to be good for assets, and vice versa. And when economies are near equilibrium, asset returns tend to be roughly equivalent to the return of cash plus a normal risk premium. The following table shows the average returns of various assets across economies in these three broad categories of conditions.

Where Things Now Stand

Nearly all major economies of the world are currently in a state of disequilibrium. This is producing large and differential pressures on policy makers to pull the levers necessary to bring conditions to the appropriate levels that will restore equilibrium and achieve their stated goals. As we look ahead, these pressures will be a key driver of asset returns as these differences play out, presenting large alpha opportunities where market pricing is at odds with what is needed to restore equilibrium.

Broadly speaking, the countries of the West all responded to the deflationary disequilibrium conditions of the pandemic with vast amounts of monetary and fiscal stimulus, which quickly swung their economies and markets into another disequilibrium of high inflation and clear overheating that persists today. And while Western policy makers have been responding to this by tightening, they have been doing so at differing degrees of aggressiveness and effectiveness that put them in different places today.

In contrast, Eastern countries like China and Japan responded to the pandemic with more control and less stimulative policies, which allowed their economies to avoid the extreme swing experienced in the West. But even here, there are differences, with China’s lockdowns through much of 2022 creating more depressed, deflationary disequilibrium conditions that would typically pressure policy makers to ease, but which Chinese policy makers are being cautious about in order to avoid financial excesses that could create instability.

Below, we show our current aggregate read of how close current conditions are to equilibrium across the largest economies in the world.

In the rest of this research, we scan across the major economies and dive more deeply into conditions driving the degrees of disequilibrium and the policy maker responses to address them. We start with Europe, as it is furthest from equilibrium and requires the most intervention from policy makers to bring down persistently high inflation pressures, and then quickly hit on the other economies (which we have written more extensively about previously).

Europe Is the Furthest from Equilibrium, with an Overheating Economy and Stretched Market Pricing Putting Pressure on Policy Makers to Tighten Further

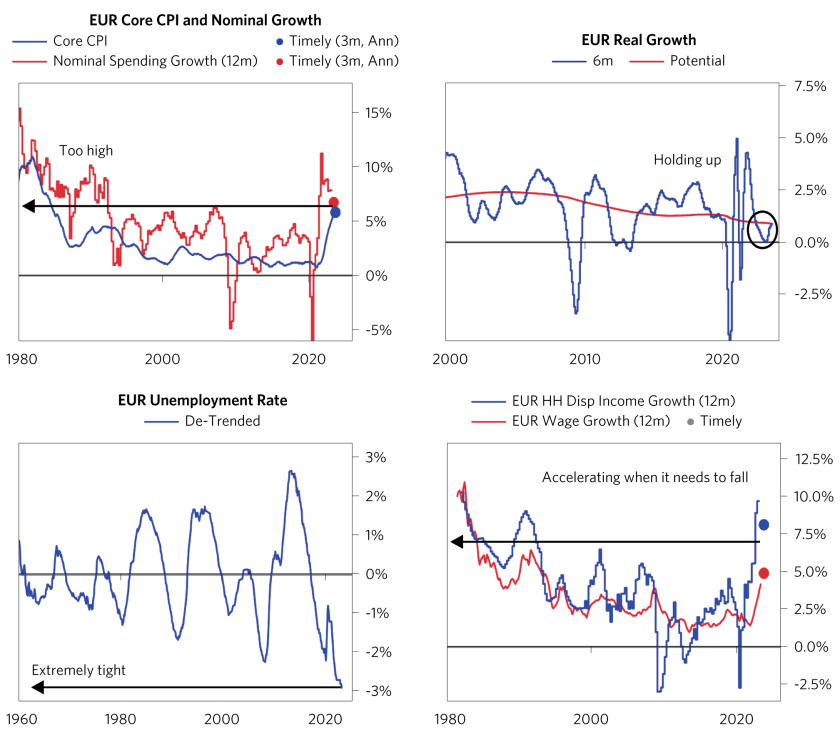

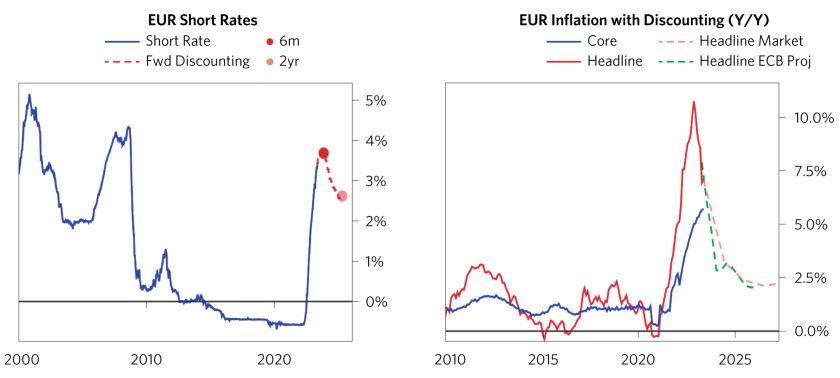

We see Europe as the major economy furthest from equilibrium, with inflation looking increasingly entrenched, even as markets are discounting a rapid normalization of conditions. Coming out of the pandemic, European nominal spending rose dramatically as a function of large fiscal stimulus, reopening-related increases in demand, and commodity price shocks. Now, the surge in spending is flowing through to higher nominal incomes and wages primarily through the labor market, as Europe’s levels of unemployment and wage growth are the tightest we’ve seen in 40 years. The tight labor market has been leading to strong wage growth, which creates a self-reinforcing inflationary dynamic by flowing through to higher nominal incomes that then allows for more spending, which then incentivizes businesses to continue hiring, keeping the unemployment rate low and wage growth elevated. Policy makers will need to tighten enough to break this self-reinforcing dynamic to bring the economy back to equilibrium.

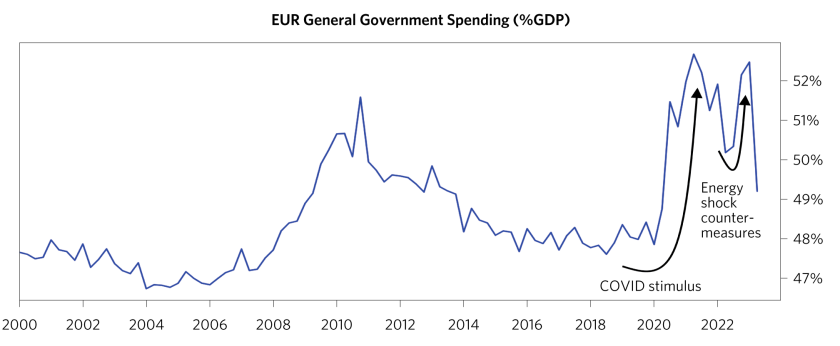

Adding fuel to the fire, the Russia-Ukraine war and resulting energy shortage forced European governments to expand their fiscal spending—to roughly the same levels of spending as during the initial phase of COVID lockdowns—in order to prevent the most acute price pressures from flowing through to households. Ultimately, this served as an effective easing, since the war’s impact on commodity prices and growth were largely evaded, as Europe experienced a relatively mild winter and global supply chains continued to ease. As such, the fiscal stimulus that would’ve helped households pay for higher fuel costs flowed through instead to greater levels of real spending, reinforcing the self-sustaining effect nominal spending has on the labor market, wages, and core inflation. This put more pressure on monetary policy makers to be tighter in order to offset this boost in spending as they attempt to bring the economy back toward equilibrium.

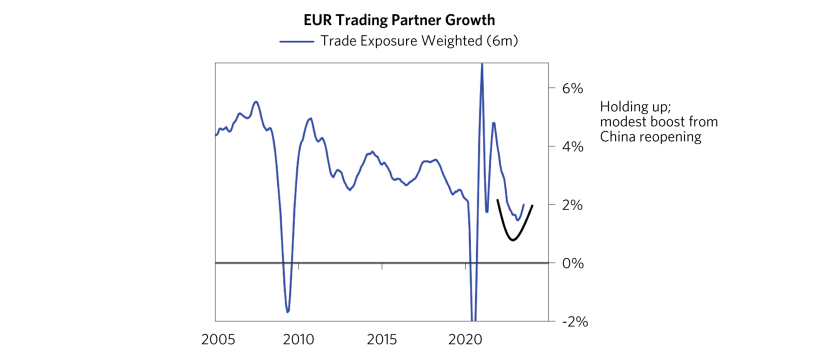

Lastly, since the start of 2023, China’s reopening has acted as an additional accelerant to Europe’s nominal spending and core inflation outlook. As China’s domestic demand comes back online, Europe’s non-commodity net export positioning means goods demand for European exports is experiencing a tailwind that counterbalances the tightening flowing through to other European goods importers like the United States. As such, labor markets are experiencing cross-cutting pressures to remain tight, which incentivizes companies to bid up wages to increase output capacity—increasing incomes, allowing high nominal spending to continue, and keeping core inflation entrenched.

Because core inflation has shown fewer signs of rolling over in Europe relative to countries like the US and Canada, short rates are discounted to continue rising over the next six months, which is warranted by conditions. However, after six months, short rates and inflation are priced to quickly fall, in essence pricing that the cumulative tightening is enough to sustainably bring conditions to equilibrium. But labor dynamics and wage growth usually take time to normalize, and if the ECB eases in line with what’s priced into markets, it could risk not making enough progress and ending in a place of too high and sticky inflation that will require further rounds of tightening and economic weakness to get back to appropriate levels.

If the goal is roughly expressed as 2% inflation with 2% real growth, inflation is currently too high and is unlikely to fall on its own because of the self-reinforcing dynamics on nominal spending that tight labor markets and wage growth are creating. To see wage-supported inflation decline, we’ll likely also need to see unemployment rise to cool labor competition, and to see unemployment rise, we’ll likely need to see corporate earnings decline—based on historical experience, likely by around 25%. This takes time to flow through, and we currently see no signs of core inflation declining. Adding it all up, the ECB is facing pressure to tighten more in level terms, or at a minimum stay tight relative to what’s currently priced six months out, to generate a sufficient decline in earnings that raises unemployment enough to cool sustained wage growth and nominal spending.

From a market pricing standpoint, bonds are particularly vulnerable. Even once you look past the short-end pricing of rates, which usually responds the most to cyclical conditions, the forward yield curve is also inverted. This suggests either no spread and squeezed risk premiums in bonds, or that the ECB is likely to keep lowering rates well into the future—both of which are risky given current conditions. Equities, on the other hand, are currently offering an adequate carry relative to a bond yield that is otherwise too low.

In North America, Tightening Is Showing Signs of Biting, but Inflation Remains Stubbornly High

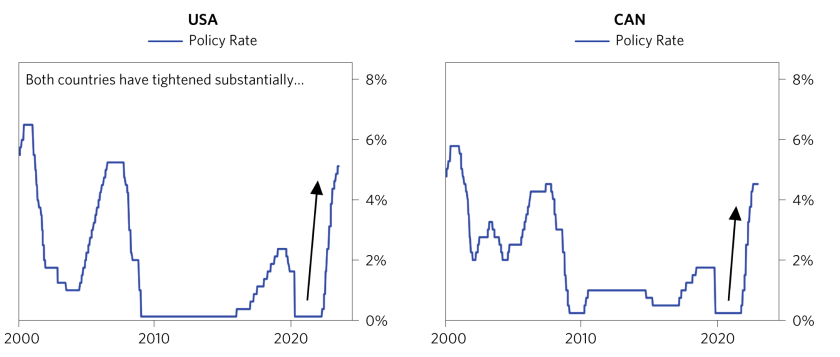

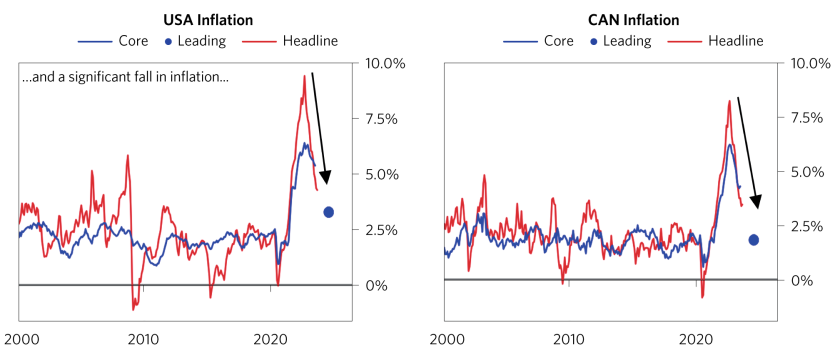

We see both the US and Canada in a bearish disequilibrium for assets. Both countries have tightened aggressively over the past 18 months or so, and the level of tightening appears to be flowing through, as credit-sensitive spending has collapsed and inflation has meaningfully decelerated. However, strong income growth has sustained nominal spending at high levels, with inflation still above target on a level basis and real growth chugging along around potential.

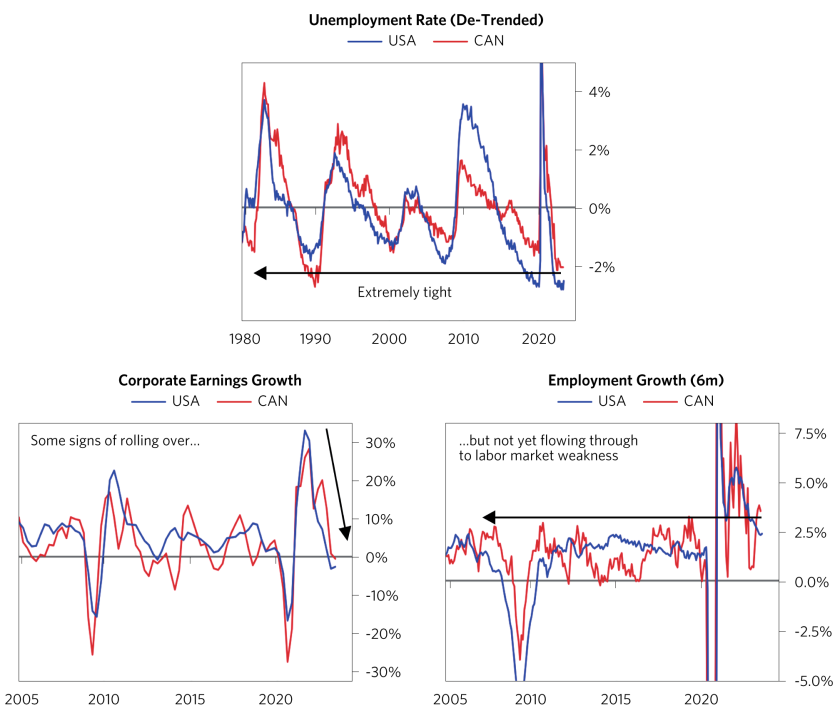

Relative to Europe, we think these economies are somewhat closer to bringing conditions back into equilibrium, given the more advanced stage of the tightening and the clearer signs of deceleration in the extremely disequilibrated inflation trends. However, ultimately solving high core inflation likely requires a sufficient hit to earnings to incentivize a rise in unemployment, which in turn loosens the labor market enough to slow wage growth to a band compatible with a 2% inflation target. And we don’t see that mix of conditions materializing yet: labor markets remain extremely tight on a level basis, continuing to pressure wages and incomes upward—and while aggregate earnings have begun to roll over somewhat, this hasn’t yet translated to a contraction in hiring. So while there are clear pressures in these economies pointing to cyclical turns, the tight labor market and pressure on wages makes it hard for central banks to normalize policy and ease as quickly as is discounted.

Relative to Bearish Disequilibria in the West, Asia Looks Highly Differentiated

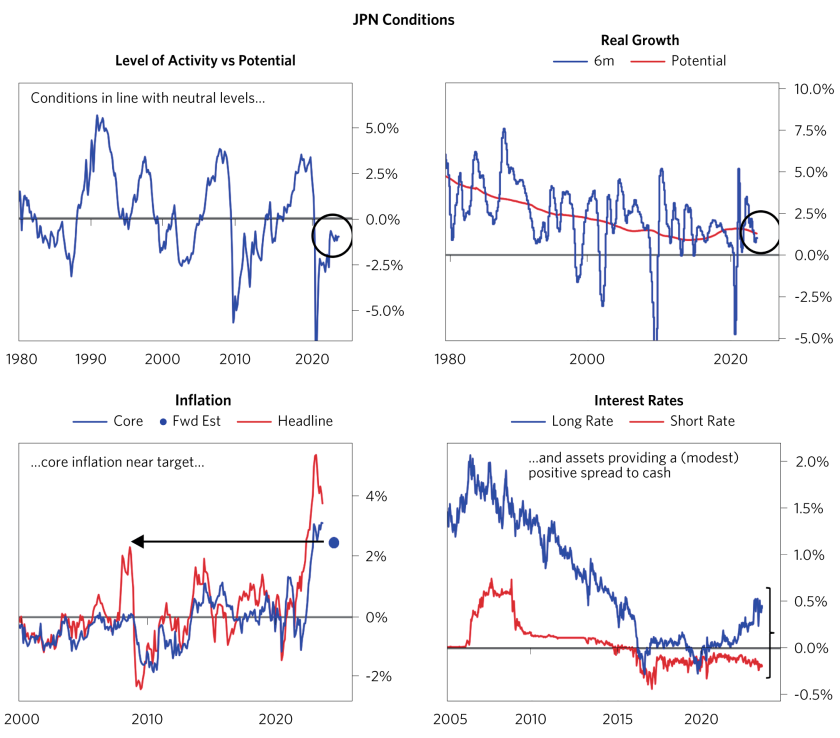

We see Japan virtually at equilibrium, with inflation at target, roughly normal levels of economic activity, and close to normal pricing of assets in relation to cash. The BoJ is running very easy monetary policy relative to these conditions (and relative to how much tightening has occurred in the rest of the world) but is appropriately cautious about shifting its stance, given global risks and no major internal pressures outside of restoring normalcy to the JGB market.

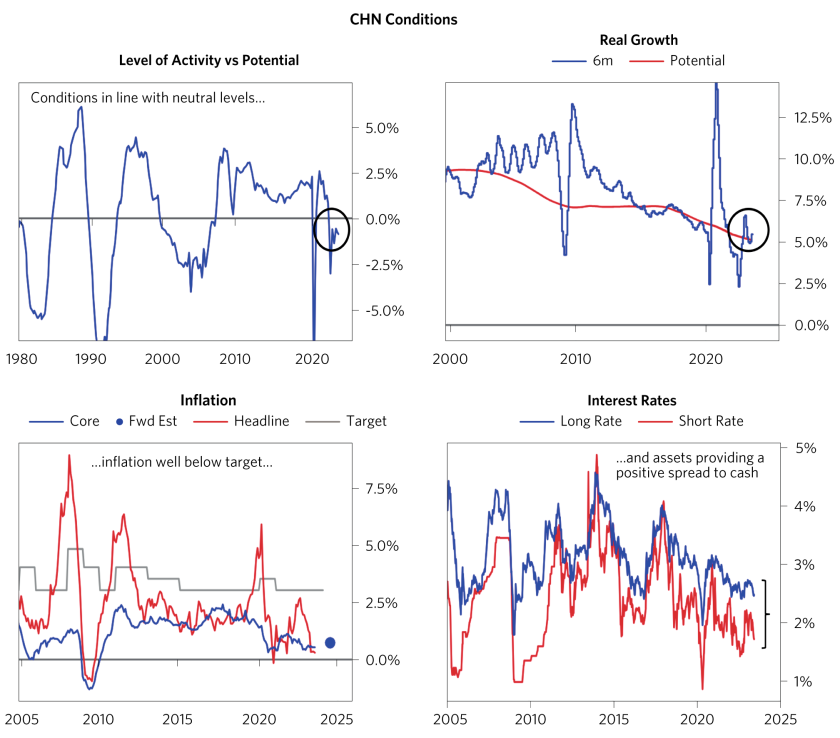

Lastly, China is likely to experience a bullish disequilibrium, as growth remains around potential, inflation remains low, and bond yields provide a normal risk premium to cash, with favorable conditions to ease in real terms. Scanning across the pressures facing policy makers, we continue to believe the current mix of pressures calls for easier policy, which, when combined with stable conditions and relatively favorable asset pricing, are a clear pressure for Chinese markets to outperform at a time when central banks around the world are experiencing pressures to stay tighter than what’s currently discounted. That being said, Chinese policy makers are being cautious, as they need to also balance concerns about easing too much and creating financial excesses and levering that could lead to instability down the line.

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES AND OTHER INFORMATION

Information contained herein is only current as of the printing date and is intended only to provide the observations and views of Bridgewater Associates, LP (“Bridgewater”) as of the date of writing unless otherwise indicated. Bridgewater has no obligation to provide recipients hereof with updates or changes to the information contained herein. Performance and markets may be higher or lower than what is shown herein and the information, assumptions and analysis that may be time sensitive in nature can change materially and may no longer represent the views of Bridgewater. Statements containing forward-looking views or expectations (or comparable language) are subject to a number of risks and uncertainties and are informational in nature. Actual performance could, and may have, differed materially from the information presented herein. Past performance is not indicative of future results.

The views expressed herein are solely those of Bridgewater and are subject to change without notice. In some circumstances Bridgewater submits performance information to indices, such as Dow Jones Credit Suisse Hedge Fund index, which may be included in this material. You should assume that Bridgewater has a significant financial interest in one or more of the positions and/or securities or derivatives discussed. Bridgewater’s employees may have long or short positions in and buy or sell securities or derivatives referred to in this material. Those responsible for preparing this material receive compensation based upon various factors, including, among other things, the quality of their work and firm revenues.

Bridgewater research utilizes data and information from public, private, and internal sources, including data from actual Bridgewater trades. Sources include BCA, Bloomberg Finance L.P., Bond Radar, Candeal, Calderwood, CBRE, Inc., CEIC Data Company Ltd., Clarus Financial Technology, Conference Board of Canada, Consensus Economics Inc., Corelogic, Inc., Cornerstone Macro, Dealogic, DTCC Data Repository, Ecoanalitica, Empirical Research Partners, Entis (Axioma Qontigo), EPFR Global, ESG Book, Eurasia Group, Evercore ISI, FactSet Research Systems, The Financial Times Limited, FINRA, GaveKal Research Ltd., Global Financial Data, Inc., Harvard Business Review, Haver Analytics, Inc., Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS), The Investment Funds Institute of Canada, ICE Data, ICE Derived Data (UK), Investment Company Institute, International Institute of Finance, JP Morgan, JSTA Advisors, MarketAxess, Medley Global Advisors, Metals Focus Ltd, Moody’s ESG Solutions, MSCI, Inc., National Bureau of Economic Research, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Pensions & Investments Research Center, Refinitiv, Rhodium Group, RP Data, Rubinson Research, Rystad Energy, S&P Global Market Intelligence, Sentix Gmbh, Shanghai Wind Information, Sustainalytics, Swaps Monitor, Totem Macro, Tradeweb, United Nations, US Department of Commerce, Verisk Maplecroft, Visible Alpha, Wells Bay, Wind Financial Information LLC, Wood Mackenzie Limited, World Bureau of Metal Statistics, World Economic Forum, YieldBook. While we consider information from external sources to be reliable, we do not assume responsibility for its accuracy. Data leveraged from third-party providers, related to financial and non-financial characteristics, may not be accurate or complete. The data and factors that Bridgewater considers within its investment process may change over time.

This material is for informational and educational purposes only and is not an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to buy the securities or other instruments mentioned. Any such offering will be made pursuant to a definitive offering memorandum. This material does not constitute a personal recommendation or take into account the particular investment objectives, financial situations, or needs of individual investors which are necessary considerations before making any investment decision. Investors should consider whether any advice or recommendation in this research is suitable for their particular circumstances and, where appropriate, seek professional advice, including legal, tax, accounting, investment or other advice.

The information provided herein is solely a guide to current expectations and not intended to provide a sufficient basis on which to make an investment decision and investment decisions should not be based on simulated, hypothetical or illustrative information that have inherent limitations. Simulated or hypothetical information are limited in part because they are based on a variety of criteria and assumptions, which might vary substantially, and involve significant elements of subjective judgment and analysis that reflect Bridgewater’s own expectations and biases, which might prove invalid, inaccurate or change without notice. Unlike an actual performance record, simulated or hypothetical results do not represent actual trading or the actual costs of management and may have under or over compensated for the impact of certain market risk factors. For these reasons, simulated or hypothetical information typically shows better results than can be achieved through actual trading. Bridgewater makes no representation that any account will or is likely to achieve returns similar to those shown, and actual returns might be substantially lower. The price and value of the investments referred to in this research and the income therefrom may fluctuate.

Every investment involves risk and in volatile or uncertain market conditions, significant variations in the value or return on that investment may occur. Investments in hedge funds are complex, speculative and carry a high degree of risk, including the risk of a complete loss of an investor’s entire investment. Past performance is not a guide to future performance, future returns are not guaranteed, and a complete loss of original capital may occur. Certain transactions, including those involving leverage, futures, options, and other derivatives, give rise to substantial risk and are not suitable for all investors. Fluctuations in exchange rates could have material adverse effects on the value or price of, or income derived from, certain investments.

This information is not directed at or intended for distribution to or use by any person or entity located in any jurisdiction where such distribution, publication, availability or use would be contrary to applicable law or regulation or which would subject Bridgewater to any registration or licensing requirements within such jurisdiction.

No part of this material may be (i) copied, photocopied or duplicated in any form by any means or (ii) redistributed without the prior written consent of Bridgewater ® Associates, LP.

©2023 Bridgewater Associates, LP. All rights reserved.