Link para o artigo original : https://www.bridgewater.com/research-and-insights/an-update-from-our-cios-2022-was-a-tightening-year-in-2023-we-will-see-its-effects

January 6, 2023

January 6, 2023

The dominant driver of markets last year was the historically large and rapid rise in interest rates. This year, the major story is likely to be the impact of higher rates as the tightening flows through to economic conditions.

The US, and to some extent European economies, entered 2022 with a head of steam. MP3 policies had worked, transitioning economies from collapse to liftoff and extremely high nominal growth, high nominal spending, and income growth that was outpacing supply and producing inflation. The policies had also produced a layer of excess liquidity that drove asset prices higher and left a store of liquidity in the hands of people and the financial system.

Central banks, particularly the Fed, faced the decision to either tighten at a much faster rate than discounted or risk the growing inflation pressures becoming entrenched. The effects of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine worsened the already dire inflation picture. The Fed chose tightening at a rapid pace.

The speed and magnitude of the monetary tightening of 2022 were among the most aggressive in history. Every movement by the Fed and other central banks was essentially the only thing driving markets, with almost every asset moving in line with its relationship to real interest rates. In the end, the markets priced in the movement in real yields. Interestingly, the markets have not priced in what we see as the very likely effects of the tightening.

The tightening’s impact on markets was big and pervasive, but its impact on economies has not yet been fully felt. The effects are coming, and if they don’t, then more tightening will be required until there is a sufficient loosening of labor markets to bring wage inflation down to a level that is consistent with sustainably achieving inflation targets.

We see a number of changes that must occur for inflation to rest sustainably near the 2% level, most of which are not priced in.

- Nominal spending growth must fall back to the range of 3-5%, as it was during the past couple of decades when inflation oscillated around central bank targets. But that will not be enough on its own.

- To achieve sustainable equilibriums, you need that level of nominal spending growth while at the same time having near-target real growth rates. That requires wage inflation to move back into the 1-3% range, similar to the past few decades.

- Given nominal spending growth of 3-5% and wage inflation around 2%, it is possible to achieve the dual mandate of full employment with stable prices; i.e., at-potential real GDP growth, at-potential output, and near-target 2% inflation.

- But given the current starting point, restoring equilibrium conditions will require an extended adjustment period of low nominal spending growth, negative real growth, and rising unemployment.

- Back of the envelope, that implies at least a 2% rise in unemployment sustained over a long enough period of time to adjust the supply/demand balance for labor, a 2% decline in real GDP, and about a 20% decline in operating earnings as an inducement for the necessary layoffs.

The Path to Equilibrium

More generally, economies work best when they are in equilibrium, and policy makers, when they are operating well, use their levers to push economies toward equilibrium. We see three necessary conditions for equilibrium:

- Spending and output in line with capacity

- Debt growth in line with income growth

- A normal level of risk premiums in assets relative to cash

The pandemic threw economies way out of equilibrium. In response, reflationary monetary and fiscal policies (MP3) were big enough for long enough that they produced an overshoot and disequilibriums in the other direction, requiring the aggressive tightening cycle of 2022 that is likely to continue into some portion of 2023.

At this point, none of the necessary equilibriums exist. Nominal spending is much higher than the output capacity of labor, producing inflation. That requires a contraction in spending, the initial effect of which is a downturn in real growth, a disequilibrium in the other direction. Interest rates remain well below nominal spending, which is supporting credit growth, which is supporting spending against the tightening of monetary policy. And inverted yield curves offer no risk premium in bonds versus cash, while equity pricing offers very little risk premium in equities relative to bonds.

Policy tools are blunt, and the path to equilibrium is likely to be iterative and volatile. Typically, the first move is to tighten to fight inflation at a time when growth is strong. Once growth has been reined in and inflation is in a downtrend, the tendency is to pause to see how things turn out. The pause tends to trigger a sharp relief rally in assets, which supports the economy, which cuts short the decline in inflation, requiring a second round of tightening. These pauses generally weaken the currency as well, adding yet another inflationary pressure that increases the odds of further tightening.

In the ’70s, most countries required three rounds of tightening. Germany was the exception as it responded aggressively enough in the first round to send bond yields and nominal spending into a downtrend starting in the early ’70s instead of the late ’70s, as was the experience of other developed economies.

We see the most likely path to equilibrium as policy toggling back and forth between tightening to bring down inflation and easing to support growth over an extended period of time. Regarding what comes next, when economies contract, central bankers will face pressures to pause. And given the long lag times from policy action to changes in economic growth and from economic growth to changes in inflation, their decisions will be made under conditions of uncertainty regarding whether they’ve done enough or too much.

The next most likely path is along the lines of Germany in the ’70s: a severe and sustained tightening that produces a much deeper downturn, resolving labor imbalances and bringing down wage inflation much more quickly.

We think that the least likely path is what is now discounted: an immediate move to equilibrium without much impact on the economy or earnings, with interest rate hikes peaking around March 2023, followed by a 200-basis-point decline in short-term rates over the following two years, without triggering a resurgence of inflation.

Europe and the UK face similar circumstances to the US, with the added complexity of the war and its effects on energy markets and the knock-on effects on their own fiscal balances. This has led to higher inflation and weaker economies, with the impact of the war making it harder to see the underlying money and credit influence on inflation. To date, the ECB and the BoE are lagging behind the Fed in the tightening cycle and are beginning to recognize this. Their conditions remain far from equilibrium and their paths to equilibrium are likely to be volatile.

The Path to Equilibrium Requires Lower Wage Inflation and the Right Conditions to Bring That About

The key variable in the path to equilibrium is a sustainable 2% inflation rate. With respect to that target, wage inflation is a point of central tendency because a) wages produce income that gets spent, and b) wages are the biggest cost item for companies, an input to pricing. Therefore, c) if wages are high, consumers have the money to spend on higher-priced items and companies have the inducement to raise prices by about that amount. This reflexive linkage is inherently self-reinforcing until something stops the cycle.

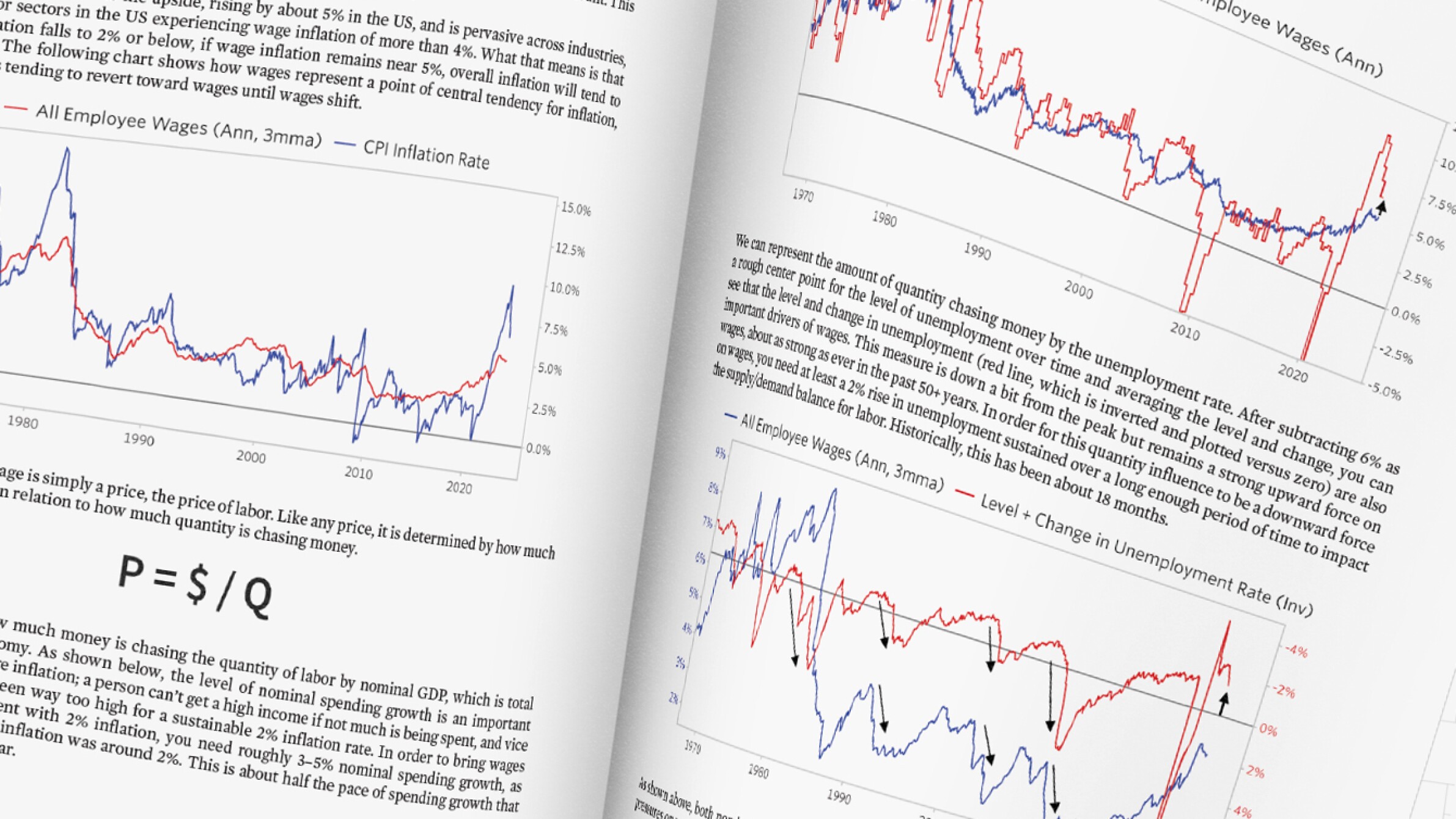

Wage inflation has broken out to the upside, rising by about 5% in the US, and is pervasive across industries, with 14 of 15 major sectors in the US experiencing wage inflation of more than 4%. What that means is that even if goods inflation falls to 2% or below, if wage inflation remains near 5%, overall inflation will tend to revert toward 5%. The following chart shows how wages represent a point of central tendency for inflation, with inflation rates tending to revert toward wages until wages shift.

So, what drives wages? A wage is simply a price, the price of labor. Like any price, it is determined by how much money is chasing quantity in relation to how much quantity is chasing money.

We can broadly represent how much money is chasing the quantity of labor by nominal GDP, which is total dollars spent across the economy. As shown below, the level of nominal spending growth is an important determinant of the level of wage inflation; a person can’t get a high income if not much is being spent, and vice versa. Nominal spending has been way too high for a sustainable 2% inflation rate. In order to bring wages down to a level that is consistent with 2% inflation, you need roughly 3-5% nominal spending growth, as existed in recent decades when inflation was around 2%. This is about half the pace of spending growth that we’ve experienced in the past year.

We can represent the amount of quantity chasing money by the unemployment rate. After subtracting 6% as a rough center point for the level of unemployment over time and averaging the level and change, you can see that the level and change in unemployment (red line, which is inverted and plotted versus zero) are also important drivers of wages. This measure is down a bit from the peak but remains a strong upward force on wages, about as strong as ever in the past 50+ years. In order for this quantity influence to be a downward force on wages, you need at least a 2% rise in unemployment sustained over a long enough period of time to impact the supply/demand balance for labor. Historically, this has been about 18 months.

As shown above, both nominal spending growth and unemployment are now upward rather than downward pressures on wages.

Within these influences, the difference between nominal spending and wages exerts pressure on unemployment because nominal spending relative to wages is an economy-wide proxy for corporate profit margins. It is logical that in order to push the unemployment rate up, nominal spending must fall relative to wages—i.e., revenues must fall relative to costs, squeezing margins, in order to induce layoffs. The chart below shows the difference between nominal spending and wages (taken from the chart above) versus changes in the unemployment rate. Throughout history, you’ve had to get nominal spending growth well below wage growth in order to bring about a material rise in the unemployment rate. The recent rise in wages was supported by nominal spending rising well above wages, producing a surge in profits and hiring. Nominal spending remains above wages, so there is not much pressure for the unemployment rate to rise until nominal spending is reduced to well below 5%. The degree of tightening that we have had so far is probably enough to have that effect in 2023. But if it’s not, more tightening will be required until it is.

Another way to look at the same dynamic is through corporate earnings. It is logical that there has never been a big rise in the unemployment rate without a decline in corporate earnings. Corporate earnings need to fall by about 20% in order to induce the degree of layoffs necessary to push the unemployment rate up by enough to bring wages down. This has also not happened yet.

Summarizing these linkages and what they imply:

- Wages are a point of central tendency for inflation and are pervasively running at about 5%. To get 2% inflation, you need roughly 2% wage growth.

- To reduce wage inflation, you need a combination of lower nominal spending growth and higher unemployment rates in order to rebalance dollars and quantity (P=$/Q).

- To get higher unemployment rates, you need nominal GDP growth to fall materially below wage growth, compressing profit margins enough to produce about a 20% decline in earnings.

- Then, these conditions must be extreme enough and long-lasting enough to alter the supply/demand balance for labor so that 2% wage growth is achieved—i.e., about a 2% rise in unemployment sustained over a period of about 18 months.

We are nowhere near having experienced this sequence of conditions, suggesting that the path to equilibrium has a ways to run, with a lot of tough central bank choices and market volatility along the way.

The Dollar Squeeze

Because the dollar acts as the world’s primary funding currency, tightening by the Fed has a large impact on other countries’ balance of payments. As that tightening drives up the dollar relative to other currencies, foreign dollar borrowers are compelled to trade ever more of their weakening currencies for dollars to service their debts, thereby driving the dollar up even further versus those currencies. Because the dollar tightening also slows global growth and demand for exports, these currency dynamics often play out against a backdrop of weakening domestic growth and deteriorating current account balances in dollar-debtor countries. This self-reinforcing cycle frequently crescendos to a balance of payments crisis in these countries, yet another disequilibrium to be resolved by some combination of eventual dollar easing, tightening in other countries, and slowing of dollar-debtor economies.

The aggressive tightening by the Fed, which has supported the dollar squeeze, has also pushed the dollar to the high end of its long-term ranges and the current account into deep deficit. This makes the current level of capital inflow the breakeven level of capital inflow required to hold the dollar steady. As a result, the dollar is vulnerable to a weakening of the US economy and a reversal of the tightening cycle in the US relative to abroad.

China and the East

Conditions in China and the East are far different from what now exists in the West. In response to the pandemic, China, Japan, and other Asian economies opted for social measures rather than aggressive monetary and fiscal stimulation. As a result, nominal spending growth is now much lower and near normal and inflation rates are at or below targets. Take note that this much divergence of inflation conditions across major economies is unusual in this day and age and is a very strong indication that the root cause of inflation in the West is the monetary/fiscal stimulation that was applied there but not in the East. This is also a clue as to the degree of tightening that will be required in economies that are experiencing a monetary-induced inflation.

While the US, Europe, and the UK must tighten aggressively to bring inflation down, China is in a position to stimulate as much as it desires. Policy makers there are not constrained by too-high inflation, and the economy is operating below potential. However, policy makers are also exercising self-restraint against the excesses of “flooding” the system with liquidity and overleveraging.

Classically, this is the time to ease and stimulate growth. Policies are headed in that direction, combined with the relief of zero-COVID constraints. Policy makers have prioritized economic stability and are expected to set the growth goal for 2023 at around 5%, while adhering to financial stability as uncompromisable. The policy intention is to gain synergies from strengthened coordination between monetary, fiscal, and macroprudential policies. Ideally, this will stimulate domestic demand while targeting small- and medium-size businesses, boosting employment, and expanding supply to achieve self-reliance across key industries. In addition, they have called for “greater efforts to attract and utilize foreign capital” supportive of their goals and have been actively encouraging it since the end of the 20th Party Congress, along with continuing property easing, supporting private enterprise, recognizing the role of market forces, expanding international business practices, and strengthening the rule of law.

Of course, the biggest unknown for China and the rest of Asia is the growing pressures from the tension and strategic competition with the US. Undoubtedly, the need for Western companies to diversify away from Chinese production will be a growing negative, as will limits on technology transfers from the West. More important are the risks that the tensions bubble up into more draconian tit-for-tat measures.

This research paper is prepared by and is the property of Bridgewater Associates, LP and is circulated for informational and educational purposes only. There is no consideration given to the specific investment needs, objectives or tolerances of any of the recipients. Additionally, Bridgewater’s actual investment positions may, and often will, vary from its conclusions discussed herein based on any number of factors, such as client investment restrictions, portfolio rebalancing and transactions costs, among others. Recipients should consult their own advisors, including tax advisors, before making any investment decision. This report is not an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to buy the securities or other instruments mentioned.

Bridgewater research utilizes data and information from public, private, and internal sources, including data from actual Bridgewater trades. Sources include BCA, Bloomberg Finance L.P., Bond Radar, Candeal, Calderwood, CBRE, Inc., CEIC Data Company Ltd., Clarus Financial Technology, Conference Board of Canada, Consensus Economics Inc., Corelogic, Inc., Cornerstone Macro, Dealogic, DTCC Data Repository, Ecoanalitica, Empirical Research Partners, Entis (Axioma Qontigo), EPFR Global, ESG Book, Eurasia Group, Evercore ISI, Factset Research Systems, The Financial Times Limited, FINRA, GaveKal Research Ltd., Global Financial Data, Inc., Harvard Business Review, Haver Analytics, Inc., Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS), The Investment Funds Institute of Canada, ICE Data, ICE Derived Data (UK), Investment Company Institute, International Institute of Finance, JP Morgan, JSTA Advisors, MarketAxess, Medley Global Advisors, Metals Focus Ltd, Moody’s ESG Solutions, MSCI, Inc., National Bureau of Economic Research, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Pensions & Investments Research Center, Refinitiv, Rhodium Group, RP Data, Rubinson Research, Rystad Energy, S&P Global Market Intelligence, Sentix Gmbh, Shanghai Wind Information, Sustainalytics, Swaps Monitor, Totem Macro, Tradeweb, United Nations, US Department of Commerce, Verisk Maplecroft, Visible Alpha, Wells Bay, Wind Financial Information LLC, Wood Mackenzie Limited, World Bureau of Metal Statistics, World Economic Forum, YieldBook. While we consider information from external sources to be reliable, we do not assume responsibility for its accuracy.

The views expressed herein are solely those of Bridgewater as of the date of this report and are subject to change without notice. Bridgewater may have a significant financial interest in one or more of the positions and/or securities or derivatives discussed. Those responsible for preparing this report receive compensation based upon various factors, including, among other things, the quality of their work and firm revenues.