Link para o artigo original: https://www.acadian-asset.com/investment-insights/equities/investor-sentiment-for-value-and-growth

Key Takeaways

- Vanguard launched the first value- and growth-labeled index funds in 1992, soon after Russell created its style indexes. While value index funds initially attracted more assets, growth index funds have consistently held a market share advantage. Flows into and out of these funds over the past 30 years can be used to gauge investor beliefs about value and growth returns.

- Estimates suggest that in the late 1990s, investors believed growth index funds would deliver returns up to 75 basis points higher per year than value funds, with that figure standing at 30 basis points in March 2024.

- Investor beliefs about future returns have not been useful predictors of future returns. When growth returns have been relatively higher, subsequent returns on Russell 1000 growth stocks have been relatively lower. Investor allocations to Vanguard growth and value index funds since their 1992 inception show a modest wealth loss of 8% over the period from 1992 through 2024.

The Origins of Index Investing

The first Vanguard index fund was launched in August 1976 with the goal of closely tracking the return of the S&P 500 index at the lowest possible cost.1 The new product had a natural justification rooted in the academic theory of market efficiency, developed and tested in the 1960s and 1970s. If the market is efficient, and beating the market by picking individual stocks is therefore impossible to do consistently, why not simply hold the overall market at the lowest cost? In 1978, the late Michael Jensen said, “I believe there is no other proposition in economics with more solid evidence supporting it than the Efficient Market Hypothesis.” Studies of U.S. and international returns, including Jensen’s own work on mutual funds, found that stock returns were unpredictable and concluded that attempts to beat the market were not worth the associated transaction costs and management fees.

The academic pendulum swung back as evidence of return predictability accumulated. In the leading examples, small stocks outperformed large ones, cheap stocks—defined by their prices relative to earnings, book value, or prices five years prior—outperformed expensive ones, and stocks with high one-year returns continued to outperform those with low one-year returns. Gene Fama and Ken French summarized a decade of research from the 1980s in two papers published in 1992 and 1993, proposing two factors: one capturing the high returns of small stocks and the other capturing the high returns of value stocks. By labeling these as “factors” and not “mispricings,” and describing stocks as “value” and “growth” instead of cheap and expensive, Fama and French focused on the possibility that market efficiency was alive and well. Small stocks outperformed because they were riskier than their larger counterparts, and value stocks were not cheap but rather riskier than stocks with better prospects for fundamental growth. Momentum and other more dynamic strategies were harder to link to risk and left out of the original Fama-French synthesis.

The academic research of the late 1970s and 1980s had the side effect of making the common practices of stock picking into systematic, or rules-based, portfolio choice. Discretionary investment strategies that advocate buying stocks with low multiples to earnings and book value emerged long before Fama and French, dating at least to Security Analysis by Benjamin Graham and David Dodd in 1934. Growth investing has also had longstanding appeal. Philip Fisher popularized the strategy with Common Stocks and Uncommon Profits in 1958.

Russell Value and Growth Indexes

With this backdrop, Russell invented passive style indexes in 1987. Soon after, Vanguard invented passive index funds style in 1992. Barnes (2021) summarizes Russell’s rationales:

Benchmarking. As a consultant to pensions, endowments, and foundations, Russell’s core rationale was to “help its clients identify successful active managers.” In so doing, Russell encouraged clients to compare their managers’ performance with funds that had similar tilts toward value or growth stocks. Value and growth stocks tended to move in separate packs, meaning that a manager’s returns might be attributed to a bias towards value or growth, not the stock-picking skill that Russell’s clients expected.

Russell also anticipated the possibility that these indexes would become investment products, citing three more rationales:

Strategic preference. Had Russell cared only about the alignment of its index development with insights from academic research, it might have created only an investable value index, and not a growth index, to help investors to take advantage of an “expected long-run outperformance of value stocks.”

Tactical preference. But instead, by offering both value and growth, Russell allowed investors to speculate on a “view that one style will outperform over a certain period.” Although the value and growth funds’ labels suggested that both had independent appeal, they were designed so no investor would rationally buy both simultaneously. An equal-weighted portfolio of Russell value and growth indexes delivered exactly the returns of a fully passive Russell 1000 market portfolio, albeit with a higher overall expense ratio and a higher tax bill.2

Portfolio completion. Russell’s final rationale was risk management. If investors found it easier to locate active managers focused on value stocks than on growth stocks, for example, they could use Vanguard’s growth index fund to “fill the hole in their portfolio” thereby taking a neutral view overall on the relative performance of growth and value.

Vanguard Value and Growth Index Funds

Five years later, in 1992, Vanguard followed Russell’s lead, launching a pair of style index funds that allowed investors to express a strategic or tactical preference for one or the other. According to Rekenthaler (2022), Bogle initially “bemoaned his progeny. He came to believe that they led to poor investor choices by tempting customers into buying the fund that had the higher recent returns.”3

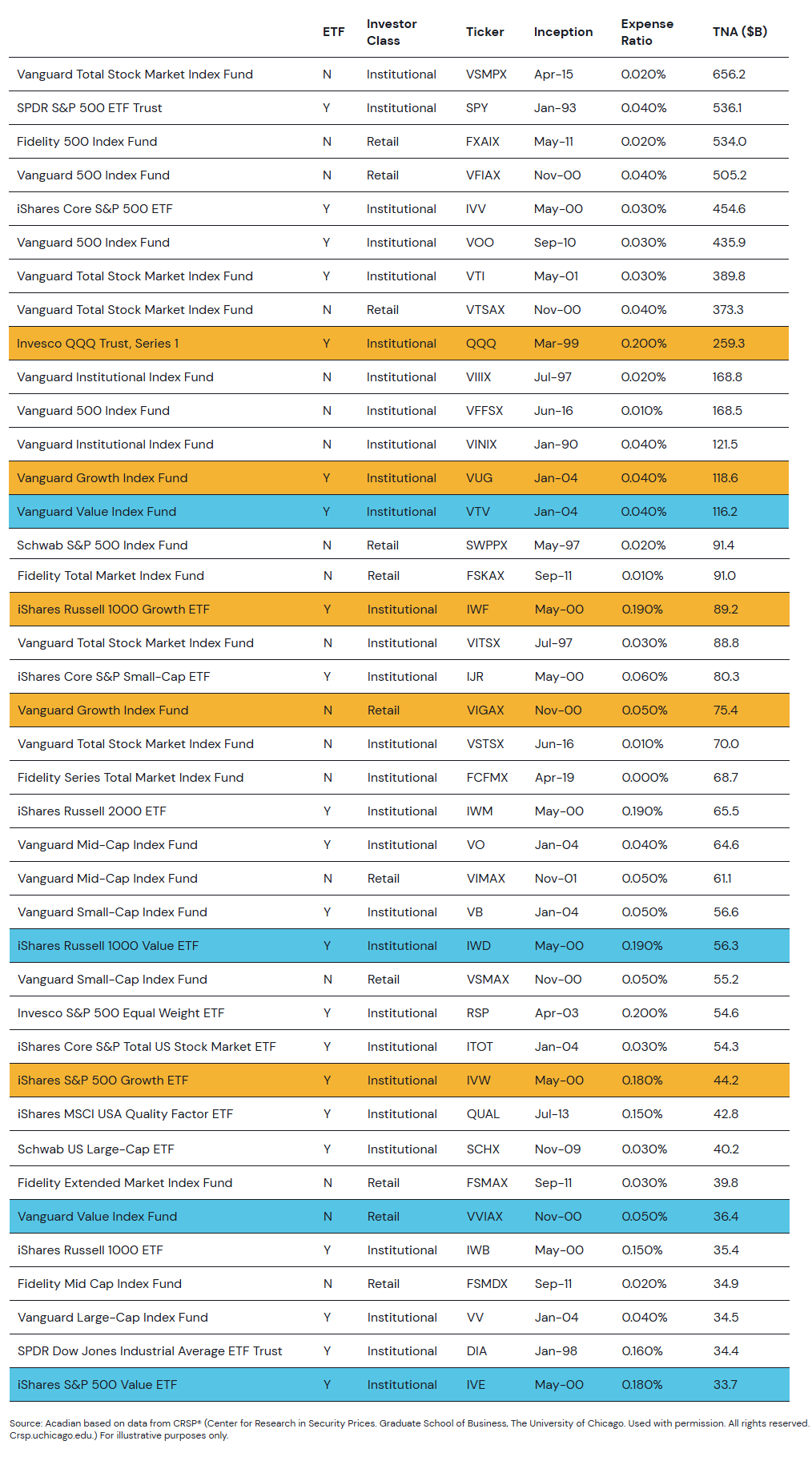

Table 1: Top Index Funds in March 2024 by Total Net Assets

Nine of the top 40 domestic index funds tracked by the Center for Research on Security Prices by total net assets are value-labeled or growth-labeled index funds.

The Market for Index Funds

From these beginnings in 1992, value- and growth-labeled index funds have grown to become some of the largest in the world. Of the top 40 domestic index funds shown in Table 1, which include both traditional mutual funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs), nine or 23% by count are growth or value funds. These nine taken together account for $823.3 billion in net assets or 13.1% of the total assets under management for these 40 funds. Net assets for all value- and growth-labeled index funds tracked by the Center for Research on Security Prices (CRSP) now total nearly $1.6 trillion.

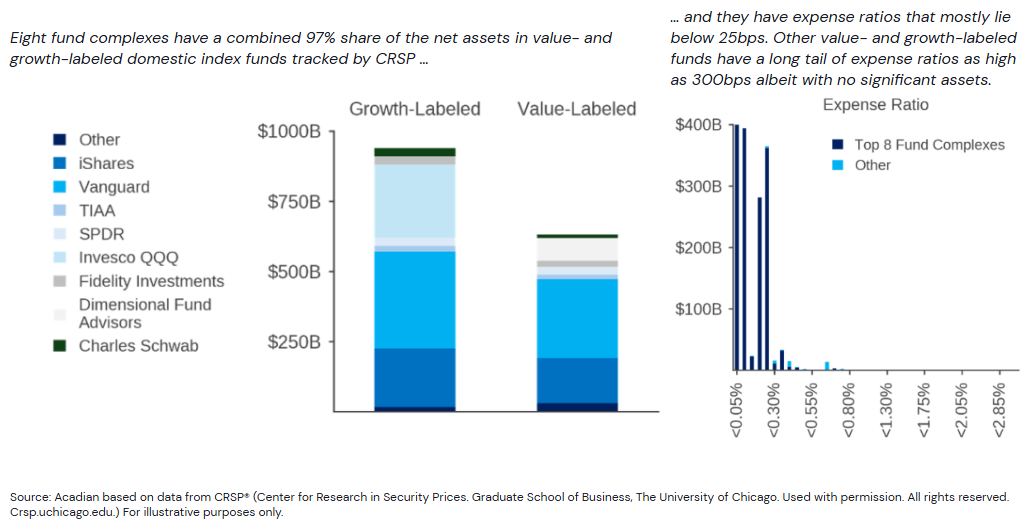

The provision of style index funds is a concentrated but competitive business, perhaps not surprising given the economies of scale. Eight fund complexes—Charles Schwab, Dimensional Fund Advisors, Fidelity Investments, Invesco QQQ, State Street SPDRs, TIAA, Vanguard, and BlackRock iShares—account for 97% of the assets under management, as shown in Figure 1-left. Vanguard, the dominant player across all indexed mutual funds, holds a 40% share. BlackRock is second, with its iShares brand focused on ETFs. Most of the value- and growth-labeled indexed assets are now in ETFs, with only 25% in traditional mutual funds, which are disadvantaged in terms of taxes and liquidity. Despite this concentration, the largest index funds by total net assets (TNA) charge ultralow expense ratios: Figure 1-right shows that 94% of assets have an expense ratio of less than 25 basis points per year, with many funds below five basis points. The analysis that follows narrows the focus to these eight large fund complexes, excluding an eclectic set of mostly higher-fee index funds that are numerous but have very little market share. Appendix 1 provides a description of this sample and the rationale for focusing on the market leaders.

Figure 1: Style Index Funds — Total Net Assets by Fund Complex and Expense Ratio

As of March 2024

A significant 60% of the total net assets in the sample now reside in growth, rather than value, index funds. This was not the case when these style funds were launched in 1992. Given Fama and French’s seminal work in 1992 and 1993, it may come as no surprise that the growth share of total net assets was less than 20% in the third quarter of 1996, as shown in Figure 2. However, this imbalance was short-lived. Growth surged to a 78% share at the peak of the Internet-fueled bull market in growth stocks that followed and never looked back. Since then, the growth-labeled share has only briefly dipped below 50% during a two-year period from 2016 through the end of 2017.4 Cumulative flows into value and growth funds, also shown in Figure 2, tell a similar story.

Figure 2: Market Share of Growth-Labeled Index Funds—Total Net Assets and Flows

After a slow start, growth-labeled index funds have consistently garnered more net assets than value-labeled index funds.

Source: Acadian based on data from CRSP® (Center for Research in Security Prices. Graduate School of Business, The University of Chicago. Used with permission. All rights reserved. Crsp.uchicago.edu.) For illustrative purposes only.

Inferring Investor Beliefs from Their Investment Choices

In recent years, the financial economics profession has adopted methods from industrial organization to study how consumers choose among financial products, including mortgages and index funds. Like markets for physical goods, such as new cars, the financial product market clears when supply equals demand. As a result, it’s no great leap to extend the same statistical tools that researchers apply to estimate the dollar value that New England car buyers place on heated seats to reveal what investors believe about relative rates of return as they allocate their portfolios between value- and growth-labeled index funds.5

Our analysis starts with the simple premise that each investor weighs a fund’s attributes against its expense ratio, which is measured in terms of annual foregone return. To infer aggregate investor beliefs about the expected returns of value- versus growth-labeled index funds, we run the following regression, where each observation represents a given style fund i at time t:

While Appendix 2 provides technical details and methodological caveats for readers interested in a deeper dive, we can express the four main elements of the expression in intuitive terms:

- The left side measures the fund’s share of either total net assets or cumulative flows among style funds at each point in time.

- The first term on the right side is the annual expense ratio expressed in basis points of initial investment.6

- The coefficients

and

and  , which are estimated via the regression, measure investor preferences for value and growth funds, respectively.

, which are estimated via the regression, measure investor preferences for value and growth funds, respectively. - “+ …” represents control variables included in our preferred specification, including four past quarterly returns that may influence return-chasing or rebalancing flows, fixed preferences for the eight fund complexes, and—since older funds typically have more net assets than newer ones—each fund’s inception date.

This regression produces a time series of  that reveals the relative preference for growth-labeled index funds. Dividing

that reveals the relative preference for growth-labeled index funds. Dividing  by converts this preference into basis points of annual return.

by converts this preference into basis points of annual return.

Figure 3 presents the results for the traditional mutual fund subsample, analyzed with cumulative flows, and shows the greatest variation in estimates of investor beliefs for growth-labeled index funds. The estimated beliefs about growth-labeled index fund returns peaked at 75 basis points higher than value-labeled funds in the late 1990s. By the first quarter of 2024, investor beliefs had settled at 30 basis points, perhaps reflecting the impact of artificial intelligence driving interest in growth stocks.

Figure 3: Investor Preferences for Value and Growth-Labeled Index Funds

Preference for growth funds over value funds versus historical average, measured in basis points of return per year

Investor preferences for growth-labeled index funds peaked in the late 1990s and stand at 30 basis points in 2024.

Source: Acadian based on data from CRSP® (Center for Research in Security Prices. Graduate School of Business, The University of Chicago. Used with permission. All rights reserved. Crsp.uchicago.edu.) For illustrative purposes only.

Four Discussion Points

1. Rational Expectations or Sentiment?

In a sense, Figure 3 treats the market for index funds as a prediction market. While investor beliefs are not directly surveyed, the regression infers the average beliefs of market participants indirectly from their behavior. Based on our 30 years of results, we see a mixed picture of the accuracy of those beliefs about future style returns.

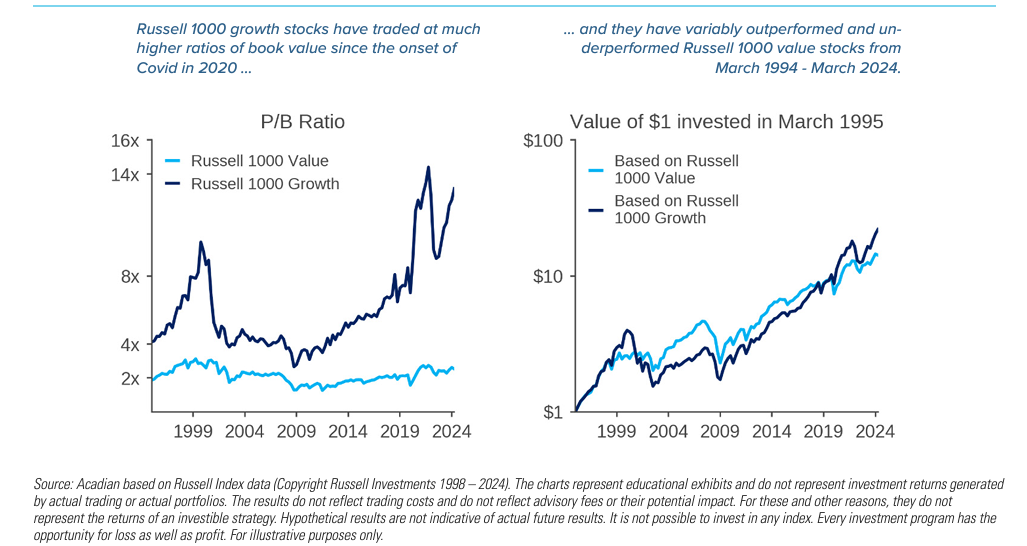

Figure 4 presents two variables that we use to gauge the nature of investor expectations. The first, in Figure 4-left, is the relative market-to-book ratio. Since COVID, the price-to-book ratios of growth stocks have been stratospheric, as firms with limited assets but strong earnings have driven the Russell 1000 Growth Index higher. The second variable, in Figure 4-right, is the relative returns of the Russell value- and growth-labeled indexes. Both figures highlight the booms and busts in the relative performance of growth stocks over the past thirty years.

Figure 4: Relative Valuations and Returns—Value Versus Growth Indexes

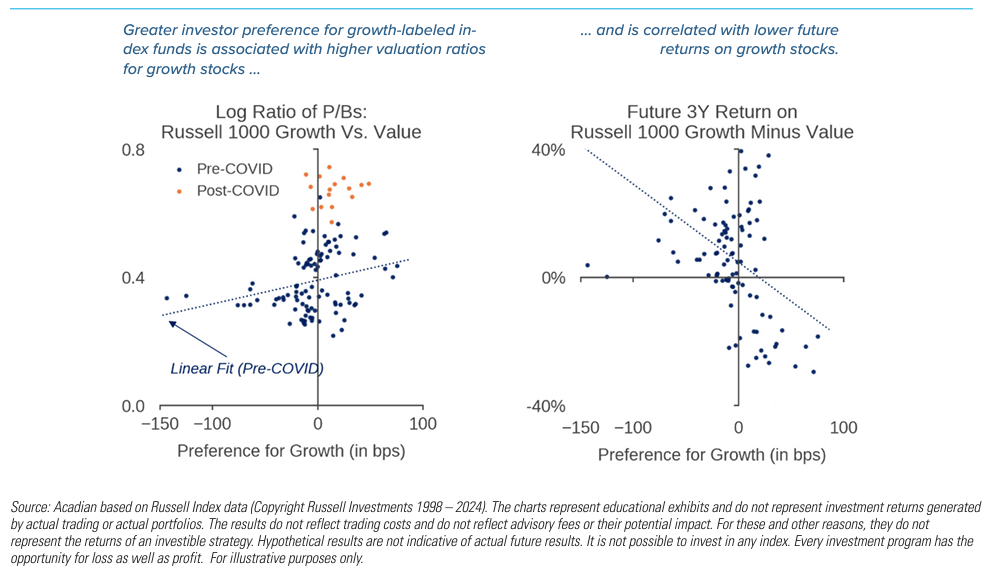

Figure 5 correlates these two measures with investors’ inferred ex ante expectations. Are investor beliefs about growth funds more positive when growth stocks are a bargain or when they are expensive relative to book value? Do growth stocks subsequently perform well or poorly when investors favor growth funds to a greater degree?

Figure 5: Valuations and Future Returns as Functions of Preferences for Growth Funds

Figure 5-left shows that investors express the greatest preference for growth funds when growth stocks’ prices are relatively high in relation to book or earnings. Figure 5-right shows that when investors favor growth-labeled index funds their subsequent three-year returns are lower than those on value-labeled funds. The poor predictive accuracy of investor preferences suggests that “sentiment for growth” is a more fitting description of Figure 3 than “reliable predictions for growth.” While these results are not particularly strong statistically—with correlations ranging from 26% to 49% in absolute value—there is no sign in Figure 5-right of the upward slope that we would expect from a reliable prediction.

2. Why Do Anomalies Persist?

An open question in financial economics is whether anomalies, once discovered, persist. The logic goes like this: Rational investors might see a newly discovered anomaly as an opportunity, then trade aggressively, and in so doing drive prices to converge and thereby eliminate the anomaly on a go-forward basis. The anomaly is said to be “arbitraged away” in a nod to the textbook definition of arbitrage that eliminates pricing differentials among identical securities. Securities that were once under- or over-valued become correctly priced as investors pursue strategies to capitalize on what was once considered anomalous mispricing.7

Some of the facts in our study of value and growth index funds are aligned with this logic of fleeting anomalies. Back in 1992, Fama and French observed that value stocks delivered anomalously higher average returns than growth stocks over the preceding 30 years. Russell and Vanguard responded by offering investors a low-cost way to capitalize on this evidence with the introduction of the value index fund. By the mid-1990s, investors had done what might be expected—they favored value.

But not all the facts are aligned. The allure of growth remained strong, whether in individual stocks with rapid growth in revenue or funds of stocks labeled as “growth.” Since the late 1990s, Figure 2 shows that investors have almost always favored growth. If growth has fared relatively better in the last 30 years than in the previous 30, it has not been because investors “arbitraged” the value anomaly. They have done the exact opposite, making growth more expensive and value cheaper. Quite possibly, the introduction of both value- and growth-labeled index funds has caused the prices of the underlying stocks to diverge instead of to converge.

3. Have The Style Index Funds Helped or Harmed Vanguard Investors as A Group?

Recall that Bogle “bemoaned his progeny. He came to believe that they led to poor investor choices by tempting customers into buying the fund that had the higher recent returns.” How did Bogle’s customers do? The structural tilt towards growth on average has been beneficial, at least in part because of the tailwind of investor flows into growth. The dynamic variation in enthusiasm for growth over time has been less beneficial, illustrated by the relationships in Figure 5-right. Relatively more positive beliefs about growth and market shares of growth index funds have not been rewarded with relatively higher growth index fund returns. This wealth loss has been modest. Appendix 3 examines the returns of the original 1992 Vanguard index funds in isolation. Investors ended up with 8% less wealth in 2024 than they would have otherwise, had all their flows into growth and value stocks been invested in a constant proportion through time, starting in 1992. This is a relatively small 29 basis points per year. Perhaps Vanguard investors, and index fund investors in general, are less prone to sentimental shifts across value and growth.

4. A Different Take: Who Is More Sentimental, Vanguard’s Value Investors or Its Growth Investors?

Considering Vanguard’s style index fund investors to be a homogenous group is partly missing the point. Recall that Vanguard adopted the Russell style indexes, which were constructed so that no rational investor would hold both at the same time: It is always more efficient to aggregate overlapping holdings in Russell 1000 Growth and Value into a single position in the overall Russell 1000.

So, it might be natural to view these investors as two distinct groups, allowing us to ask a different question: Have their flows, taken separately, been timed well over the period from 1992 through 2024? The short answer is that neither group has done particularly well, but growth investors have fared worse by this yardstick. Appendix 3 provides details. Growth investors as a group lost 156 basis points per year in poorly timed flows, adding more to their positions at relatively high valuations and adding less or subtracting from their positions at relatively low valuations. Value investors as a group also had poor timing, albeit losing only 82 basis points per year.

Conclusion

Vanguard launched a pair of index funds in 1992, giving us more than 30 years of data to examine investor beliefs about the returns to value and growth. After an initial market share advantage, investors have reliably preferred growth to value, measured either by the share of assets under management or cumulative flows. Our estimates of investor beliefs about the relative returns to growth peak at 75 basis points per annum in 1999 and now stand at 30 basis points. Those past beliefs have not been predictive of future returns, however. Analysis of Vanguard’s products from 1992 to the present shows that value and growth index fund investors, taken together, suffered a modest wealth loss of 8% through their timing of value and growth. Among them, growth investors are more prone to sentiment, with greater inflows at peak valuations.

Please refer to Appendix in the PDF download version of this paper for additional information and details on data presented herein.

References

Baker, M., M. Egan, and S. Sarkar, Demand for ESG, NBER Working Paper, 2024.

Baker, M., M. Egan, A. McKay, and H. Yang, Expectations for Value, Work in Progress, 2023.

Barnes, M., Russell Growth and Value Indexes: The enduring utility of style, Russell Investments, 2021.

Ben-David, I., J. Li, A. Rossi, and Y. Song, “What do mutual fund investors really care about?” The Review of Financial Studies

35, no. 4 (2022): 1723–1774.

Benetton, M. and G. Compiani, “Investors’ beliefs and cryptocurrency prices.” The Review of Asset Pricing Studies 14, no. 2

(2024): 197–236.

Buchak, G., G. Matvos, T. Piskorski, and A. Seru, “Fintech, regulatory arbitrage, and the rise of shadow banks.” Journal of

Financial Economics 130, no. 3 (2018): 453–483.

Dannhauser, C. and J. Pontiff, Flow, Working Paper, 2024.

Dichev, I, “What are stock investors’ actual historical returns? evidence from dollar-weighted returns.” American Economic

Review 97, no. 1 (2007): 386-401.

Egan, M., A. J. MacKay, and H. Yang, “Recovering investor expectations from demand for index funds.” Review of Economic

Studies 89, no. 5 (2022): 2559–2599.

Fama, E. F. and K. R. French, “The cross-section of expected stock returns.” Journal of Finance 47, no. 2 (1992): 427–465.

Fama, E. F. and K. R. French, “Common risk factors in the returns on stocks and bonds.” Journal of Financial Economics 33,

no. 1 (1993): 3–56.

Fisher, P. A., “Common Stocks and Uncommon Profits,” (Harper & Brothers, 1958).

Frazzini, A. and O. A. Lamont, “Dumb money: Mutual fund flows and the cross-section of stock returns.” Journal of Financial

Economics 88, no. 2 (2008): 299–322.

Graham, B. and D. L. Dodd, “Security Analysis,” (McGraw-Hill, 1934).

Pontiff, J. and D. McLean, “Does academic research destroy stock return predictability?” Journal of Finance 71, no. 1: (2016)

5–32.

Rekenthaler, J., Vanguard’s other index-fund invention: Should Jack Bogle have lamented his subsequent creation?,

Morningstar, May 27, 2022.

Xiao, K., “Monetary transmission through shadow banks.” The Review of Financial Studies, 33, no. 6 (2020): 2379–2420.

Legal Disclaimer

These materials provided herein may contain material, non-public information within the meaning of the United States Federal Securities Laws with respect to Acadian Asset Management LLC, BrightSphere Investment Group Inc. and/or their respective subsidiaries and affiliated entities. The recipient of these materials agrees that it will not use any confidential information that may be contained herein to execute or recommend transactions in securities. The recipient further acknowledges that it is aware that United States Federal and State securities laws prohibit any person or entity who has material, non-public information about a publicly-traded company from purchasing or selling securities of such company, or from communicating such information to any other person or entity under circumstances in which it is reasonably foreseeable that such person or entity is likely to sell or purchase such securities.

Acadian provides this material as a general overview of the firm, our processes and our investment capabilities. It has been provided for informational purposes only. It does not constitute or form part of any offer to issue or sell, or any solicitation of any offer to subscribe or to purchase, shares, units or other interests in investments that may be referred to herein and must not be construed as investment or financial product advice. Acadian has not considered any reader’s financial situation, objective or needs in providing the relevant information.

The value of investments may fall as well as rise and you may not get back your original investment. Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance or returns. Acadian has taken all reasonable care to ensure that the information contained in this material is accurate at the time of its distribution, no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to the accuracy, reliability or completeness of such information.

This material contains privileged and confidential information and is intended only for the recipient/s. Any distribution, reproduction or other use of this presentation by recipients is strictly prohibited. If you are not the intended recipient and this presentation has been sent or passed on to you in error, please contact us immediately. Confidentiality and privilege are not lost by this presentation having been sent or passed on to you in error.

Acadian’s quantitative investment process is supported by extensive proprietary computer code. Acadian’s researchers, software developers, and IT teams follow a structured design, development, testing, change control, and review processes during the development of its systems and the implementation within our investment process. These controls and their effectiveness are subject to regular internal reviews, at least annual independent review by our SOC1 auditor. However, despite these extensive controls it is possible that errors may occur in coding and within the investment process, as is the case with any complex software or data-driven model, and no guarantee or warranty can be provided that any quantitative investment model is completely free of errors. Any such errors could have a negative impact on investment results. We have in place control systems and processes which are intended to identify in a timely manner any such errors which would have a material impact on the investment process.

Acadian Asset Management LLC has wholly owned affiliates located in London, Singapore, and Sydney. Pursuant to the terms of service level agreements with each affiliate, employees of Acadian Asset Management LLC may provide certain services on behalf of each affiliate and employees of each affiliate may provide certain administrative services, including marketing and client service, on behalf of Acadian Asset Management LLC.

Acadian Asset Management LLC is registered as an investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Registration of an investment adviser does not imply any level of skill or training.