Link para o artigo original: https://www.bridgewater.com/research-and-insights/larry-summers-and-bob-rubin-join-our-cios-to-discuss-the-surprising-economic-cycle

Editor’s Note: A portion of this podcast contains charts, which are shown in the video player when referenced by the speaker.

We are living through a cycle that is playing out very differently than previous cycles over the last few decades. In particular, we’ve seen a situation where inflation rose to multidecade highs, the Fed hiked rates at one of the fastest paces in history, and yet the result has been a relatively moderate outcome—with growth staying resilient and inflation coming back down toward 2%.

We reached out to former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers to explore these dynamics—and any other big topics on his mind—with our CIOs and senior investors. And Larry had the good idea of including his friend Bob Rubin in our discussion as well.

Both Larry and Bob have had illustrious careers in government and the private sector. Larry was the 71st Secretary of the Treasury, president of Harvard University, chief economist at the World Bank, and now serves as an OpenAI board member. Bob had a long career at Goldman Sachs, where he served as co-senior partner and co-chair. He was the 70th Secretary of the Treasury, preceding Larry, and before that was the director of the newly created National Economic Council.

The full conversation was over two hours long, so we’re sharing some of the highlights from that discussion with a focus on the biggest questions facing investors today. For example, why has growth remained so resilient despite such a rapid hiking cycle? Why has inflation fallen so quickly without a recession? And you’ll hear both Larry and co-CIO Greg Jensen discuss their perspectives on these issues and how they’re thinking about the outlook going forward.

You’ll also hear Larry and Bob discuss questions like: is the US budget deficit now approaching dangerous levels? What do we make of the dollar’s exceptional strength and its outlook from here? And how will breakthroughs in artificial intelligence flow through to the economy?

We hope you enjoy the conversation.

Note: The views of external guests do not necessarily reflect the views of Bridgewater.

Note: This transcript has been edited for readability.

“So I was very much not a fiscal hawk in the 2011-19 period. But in economics, unlike physics, you have to adjust your way of thinking to the fact that the world changes quite profoundly. And in the aftermath of the big run-up of debt and the many reasons to have real interest rate increases, it has seemed to me since 2021, with growing degrees of alarm, that we have a very, very serious fiscal situation developing, which is likely to manifest itself in one of substantial inflationary pressure, substantial indigestion in the Treasury markets with financial chaos, or substantial crowding out of what would be otherwise valuable private investment.” —Larry Summers, former Treasury Secretary

Jim Haskel

I’m Jim Haskel, editor of the Bridgewater Daily Observations. As we’ve covered in a number of our BDOs, we’re living through an economic cycle that’s playing out very differently than previous cycles over the last few decades. And in particular, we’ve seen a situation where inflation rose to multidecade highs, the Federal Reserve responded by hiking rates at one of the fastest paces in history, and yet, the result has been a relatively moderate outcome, with growth staying resilient and inflation coming back toward the Fed’s 2% anchor.

One of the most avid BDO readers is former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers. So we reached out to him to explore these dynamics, and any other big topics on his mind, with our CIOs and senior investors. And Larry had the good idea of including his friend Bob Rubin in our discussion as well. So, for context, Larry was the 71st Secretary of the Treasury. He was the president of Harvard University, the chief economist at the World Bank, and he now serves as an OpenAI board member. Bob Rubin had a long career at Goldman Sachs, where he served as co-senior partner and co-chair. He was the 70th Secretary of the Treasury, preceding Larry, and before that, was the director of the newly created National Economic Council. And that’s just, really, the highlights of their careers, as they’ve done so much more.

The full conversation was very long—it was actually over two hours. So what we’ve done is gone through and pulled out some of the highlights from that discussion that we’re sharing with you today in the latest installment of our Inside the Research Engine series.

So with that, let me now bring in BDO Deputy Editor Jake Davidson, and Jake, maybe you can give us some color on what those highlights were.

Jake Davidson

Thanks, Jim. And in terms of the highlights, while the meeting included many of our investors, the excerpts we picked focus on Larry Summers, Bob Rubin, and co-CIOs Greg Jensen and Bob Prince. So those are the voices our listeners are going to hear.

The goal with these highlights was to pick the ones that address what are really some of the biggest questions facing investors today. So, for example, why has growth remained so resilient despite such a rapid hiking cycle? Why has inflation fallen so quickly without a recession? You’ll hear both Larry and Greg discuss their perspectives in a lot of detail on these issues and how they’re thinking about the outlook going forward. Then Larry and Bob Rubin also discuss questions like, is the US budget deficit now approaching dangerous levels? What should we make of the dollar’s exceptional strength and its outlook from here? And how will breakthroughs in artificial intelligence flow through to the economy?

Jim, as you said, we tried to cut it down, but even this edited version lasts about an hour. So we’ve included chapters in the podcast player so that listeners can easily skip to parts of the podcast that are most relevant to them.

Chapter 1: Larry Summers on Why the Economy Has Remained Resilient

Jim Haskel

So with that, let’s get right into the conversation, starting with Larry Summers. We can listen here about what he thinks the two biggest questions are that have surprised economists over the past few years.

…

Larry Summers

When I think about the sort of dynamics of understanding major economic statistics over the last few years, I think of there being two large questions and two things that I think would be surprising to longtime observers of the economy.

The first is that usually when the Fed jacks interest rates up by 5 percentage points in a year and a half or so, the economy turns down and has a recession. That didn’t happen this time. And that—as I was fond of noting a couple of years ago, and turned out, so far at least, to have not been right—I used to say, whenever it’s the case that unemployment is below 4% and inflation is above 4%, recession follows and/or inflation stays high. Inflation does not fall substantially without a meaningful slowdown in economic activity.

Both of those kinds of regularities have been challenged by the recent experience. That seems important to understand. My view has been that I have two what I regard as reasonably good explanations for the first and am more puzzled by the second.

With respect to the first, my view is that the neutral interest rate is a structural feature of an economy that is determined by various aspects of household and business savings behavior, various aspects of business and residential investment behavior, and the posture of fiscal policy. And it was my judgment for the almost 30-year period, from the 1990s through the beginning of COVID, that there were substantial structural factors driving toward higher saving and lower investment propensities. That those were equilibrated by normal or neutral interest rates declining quite substantially. That neither saving nor investment were all that responsive to interest rates. Therefore, not-that-huge changes in savings and investment behavior could lead to fairly dramatic changes in the neutral interest rate. That the fiscal policy had a kind of passive role in responding to those pressures.

You saw reduced labor force growth drive reduced investment behavior. You saw higher inequality drive higher saving. You saw more retirement drive more retirement saving. You saw a change in the nature of capital goods that meant that the price of capital goods was going way down so that the dollar volume of saving to do a given thing came way down. And I would cite examples like the fact that it started taking 600 square feet per lawyer in a law firm rather than 1,200 square feet, or various changes brought about by information technology. The fact that my generation tended to like living in suburbs and my kids generally tended to like living in apartments also affected the volume of investment.

So I thought the neutral interest rate declined, and I think what has happened since then is that a variety of structural features have raised, quite substantially, the neutral rate. A huge change in the normal posture of fiscal policy, more green investment, the population becoming aged rather than aging so that there’s more dissaving relative to saving. Most recently, some substantial increase in energy investment associated with AI in addition to the green transition.

And so the neutral interest rate rose substantially to equilibrate things. If the Fed raises interest rates with a constant neutral interest rate, that is substantially contractionary. If the Fed raises interest rates in line with an increase in the neutral rate, that is not contractionary. If you think that neutral interest rates rose by 2, 2.5 percentage points, then the magnitude of the contractionary impulse is that much smaller. I think that’s probably the most important thing. I think that’s magnified by the fact—and I think you guys kind of say that in your stuff.

I think another thing that has gone on is that I think the savings/investment balance has become less sensitive to interest rates. More people are locked in long and therefore are not sensitive to interest rates—that’s a thing you guys emphasize a lot. A thing I emphasize is that if investment is a new factory, it’s very cost-of-capital-sensitive. If it’s a car, or a cell phone, or an IT system that’s only going to last five years, it is much less cost-of-capital-sensitive.

Another thing that I emphasize is that when there’s a lot of government short-term debt out there, then mechanically when interest rates go up, disposable income goes up. Which, other things equal, means more spending. And that’s a bit of an offset to the general tendency of higher interest rates to compress demand.

So I think it’s also true that if saving and investment become less interest-sensitive, then the capital market becomes more like the oil or wheat market, where relatively inelastic supply and relatively inelastic demand mean more price volatility in response to demand and supply shocks. And that that’s part of what’s going on over the last generation, contributing to: how come we weren’t getting inflation in a big boom puzzle in the 2010 decade? And how come we’re not getting more of a contraction right now?

So that’s my take on the aggregate demand interest rate thing.

Chapter 2: Larry on the Decline of Inflation

Larry Summers

I think the second question is what is it that explains the inflation dynamic? I think the theories that (a) it was all inherently transitory and had nothing to do with monetary and fiscal policy and all to do with COVID and that (b) changes in the gouging propensity are an important cause of inflation fluctuations are roughly ludicrous. And that the better way to understand the price of products is to think about supply and demand and shocks to the two of them.

And we had a massive shock to aggregate demand when we fought half of World War II in 2021 and in 2022, in terms of the expansion in fiscal policy that led to substantial upward price pressure. Of course, that price pressure manifested itself much more severely in sectors where supply was more inelastic than where supply was more elastic. But to blame that on sectoral developments in those sectors was a confusion, and it further committed the error of not understanding that because people were paying higher gasoline prices or higher car prices, for example, they had less money and were spending less on other things, which was contributing to disinflation in other sectors. So from my perspective, Milton Friedman, as always, overdid it, but was capturing stark truth when he said that inflation is about the overall price level, and that’s a sharply distinguishable subject from relative prices.

I think I missed, and there was more disinflation than I would have expected, because inflation expectations remained better anchored than I would have expected them to. Which is mostly a reflection of the fact that we had 30 years of price stability. And so, just as it really took quite a long time during the Vietnam War for inflation to substantially accelerate, when the Fed and fiscal policy were way behind the curve during the Vietnam War, I think the fact that the Fed eventually did step up, fairly dramatically, kept expectations more anchored than they would have been, and I think we caught some breaks in terms of what happened to food prices, what happened to immigrant labor flows, and to gas and energy prices. So I think we were beneficiaries of positive supply shocks with anchored expectations.

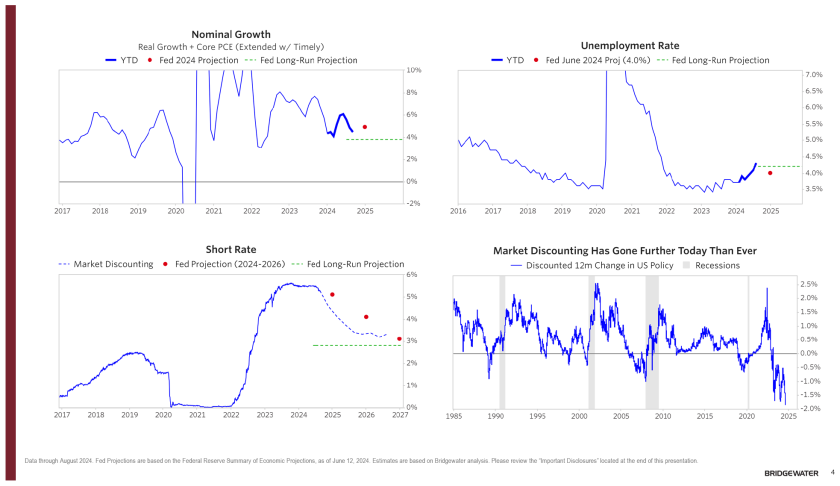

From that perspective, I think it is likely—and here I think I agree with you that if you think the neutral rate is in the 4s, and you think we’ve been the beneficiary of supply shocks and who knows what’s coming next, you don’t think the central tendency is that the Fed should cut interest rates by 225 basis points over the next 18 months. And so I would bet on less inflation cutting than the market does, though I think it’s always important to distinguish one’s degree of conviction. When I looked at the Fed dot plot in May of 2021 saying that rates would be zero until the summer of 2024, I thought I was looking at insanity. When I look at 225 basis points of cutting from here, it looks high relative to the way I understand things, but it doesn’t look insane from my perspective.

Chapter 3: Bob Rubin on the Big Dynamics He’s Watching

Greg Jensen

Great, thanks Larry. There’s so much to dig into there. Bob, I think it would be great if you jumped in with what you think the most important points are and anything you disagree with Larry on, and then we can go from there.

Bob Rubin

I guess the only other comment I’d make is: Larry talked a lot about the Fed. I first met Larry in 1983, so we’ve had a long time to disagree about things. I’ve always felt that people overstate the role of the Fed in the economy. And I’m not an economist; I’m just a retread lawyer. But I’ve been around this for five decades, and basically that whole time, in one way or another, I’ve had responsibilities with respect to risk-taking, including at Goldman Sachs for a long time.

I think the Fed is one factor, but I think it’s only one of many factors. Looking forward, as an investor—which I happen to be—and also having consulting relationships with a number of organizations, the things I worry about most are the election because I have some very strong views as to what the effect can be with the two different results. I think geopolitical matters are obviously enormously risky. I think that our fiscal situation and climate change, while they’re long-run risks, can have short- or intermediate-term impacts, and I think you can see that already in the effects of climate change on supply chains and immigration. So I think we live in a very dangerous world, and I think the Fed is one factor, but it’s only one of many factors.

Now, on the plus side, people on the consumer side in our firm say, “We’re in a slowdown,” but there’s still some strength. There’s still some momentum. We’ll see where that goes, but I guess my view is you still have some meaningful momentum in the economy. If I were the Fed—this is me, and I don’t profess any expertise with this, but I’ve been around it for a long time—I would be worried about the possibility of a slowdown becoming too serious, but I would be more wary of the inflation side. Because I think if inflation would regenerate, it’s something Volcker once said to me—I’ve never forgotten it—Paul said that inflation can take on a life of its own. Inflation expectations, psychology—and it’s much harder to deal with than recession. And since I think that’s right, if I were the Fed, I would be very, very worried about this.

The only other factor I’ll mention is AI. I know Larry is on the board of OpenAI, so he knows a ton about it. But I also know a little bit about it because I’ve been taking tutorials for the last 11 months because it seemed to me this is going to be an important part of our lives. I think that as one thinks about, let’s say, the intermediate term—that’s a big deal. Now, that could be good or bad, with all sorts of considerations. I also think this election is an enormous deal. And I’m not being partisan right now, but if you look at the stuff that Trump has said about the Fed, the weaponization of the DoJ, tariffs, Article 5, and all the rest, I think he really poses enormous risks. And I think the markets just don’t seem to care about it. So that’s a very brief overview of my view of the world.

Chapter 4: Co-CIO Greg Jensen on How He’s Seeing the Cycle

Jake Davidson

Now you’ll hear an excerpt from Greg on how he’s thinking about the economy today. Greg talks about the limits we see the economy and markets running up against, which aspects of the cycle have played out in a more typical manner compared to history and why other aspects have played out very differently, and then, looking ahead, whether the private sector will be able to take over from the public sector in terms of being the primary driver of growth. Here’s Greg.

Greg Jensen

Before I get into the mechanics, see the kind of big limits that we’re worried the world is kind of hitting on, and to hit on some of these points.

The first limit is how far can the government step into the economy? Because I do think, when you look at the linkages, why did the 4% unemployment, 4% inflation thing not work out the way it did historically? I think it’s largely because the players have changed so much. That who’s proactive and who’s reactive have changed so much. Sharing this, like the first limit that we hit was the limit of interest rate policy. In 2008, interest rates go to zero, and they’re still not stimulative. You couldn’t get to the rate necessary—given how high private sector debt was—to stimulate the economy. So you needed the government to be the proactive party, which of course leads to the quantitative easing—this is the Fed balance sheet surging. And as you guys described, we sort of hit some limits associated with the Fed balance sheet being the proactive agent in markets from the fact that that had a lot of effect on wealth.

So then, you hit sort of the limits of QE in that it really did flow through, in our view, into financial assets but less so to the economy, which leads to sort of the need for fiscal to come on. And that is the next major thing that happens, which is you get this wave in fiscal policy. So just like from 1982 or so to 2008, every cycle, the Fed did more. Every cycle they eased more in the recession, and every cycle they tightened less.

So you see this basic move since 1982 of every bottom in interest rates lower than the bottom that preceded it, and every peak in interest rates lower than the peak that preceded it. And that, we believe, was because debts in the private sector keep increasing. That means it takes more to stimulate more debt and less to slow down the economy when you need to tighten. And you hit the limit of that here and you go to this.

And now you’ve got the opposite with fiscal, I mean, you’ve got kind of the equivalent of every interest rate cycle being more extreme than the one before with the budget deficit. This is the budget deficit here. Now, every cycle, the peak in the deficit is higher than the one that preceded it, the bottom—like, i.e., the surplus in 2000—but the subsequent bottoms in deficits after it are higher than the ones that preceded it. And I do think this is the question of: will this continue? Will the government budget deficit be the mechanism? Although this budget deficit got to the point where it did create inflation—we could talk about that in a second. But that led back to at least now you have interest rates that are positive, which means there’s some degree to which interest rates can go back to the role of managing private sector incentives and creating some stimulation. So understanding those limits of: are there limits to fiscal policy, and how the fiscal policy dominance has changed the linkages, is really important. I’ll touch on that in a sec.

And the second thing is the point about, you said, Bob, that the only place you want to be in the world is the US. And that might be true, but that is certainly what everybody thinks, which is 65% of the global equity market cap is in the US, despite only being 25% of global GDP. So we are just so much better, and the market expects us to be so much better than everybody else on this whole corporate thing. There’s a question of how tolerable is that to the rest of the world? When will there be limits on what US corporations can do around the world? 65%? 90%? 100%? How long can US equities outperform everybody else? How long can US corporates dominate everybody before there is a reaction of some type, or it just doesn’t work out that way and other countries do?

And of course, the corresponding chart internally is the tech share of the US economy: 40% of the market cap of the US economy is tech. How much can, essentially, the virtual economy, etc., be dominant before there’s a reaction in other ways? Those are other limits that we think about. Both the limits, literally, of the pricing—the pricing is very extreme—but also the limits of policy, etc., to allow these things to continue.

So now just getting into the mechanics, and I wanted to make this point related to what Larry was saying and what has happened.

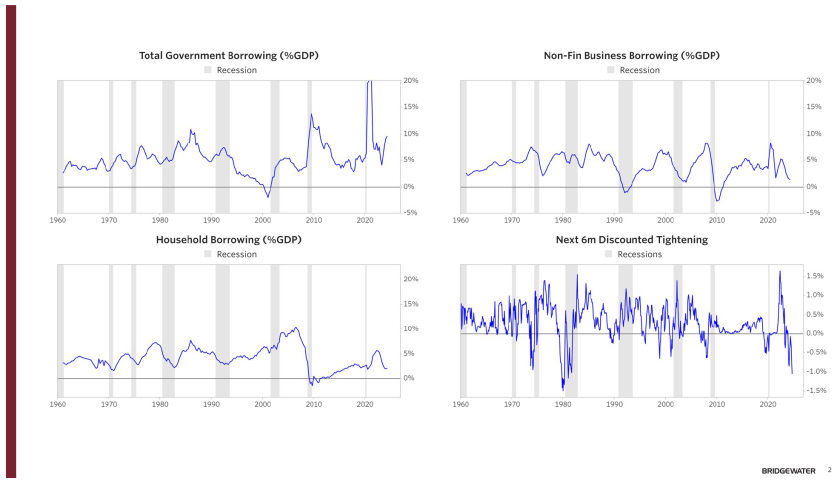

I think it’s so interesting that if you took this picture and showed it to me or showed it to—we have an AI now called AIA that studies markets, etc., it says: OK, I can tell you what’s happening. And if you had basically said this chart shows what happened to household borrowing after the Fed tightening, what happened to business borrowing after the Fed tightening, and what happened to the budget deficit. So basically, you had the Fed tighten, household borrowing fell, business borrowing fell, and the budget deficit rose. That’s actually pretty normal. That would be like, OK, well that’s normal, they tightened and household borrowing and business borrowing all fell. You’re likely in a recession. That’s why the budget deficit is going up because tax receipts went down, and there’s lots of easing discounted. This actually, from a flows perspective, looks normal.

The reaction—one thing I’d say a little different than Larry—the reaction to the tightening in terms of borrowing was pretty normal. It’s like, OK, this is the business borrowing decline when Volcker tightens. If you look at business borrowing declines in recessions, we had a normal business borrowing decline. We also had a normal household borrowing decline. What we didn’t have is a consumption and income decline, and that’s because actually the proactive items were the fiscal—the order was flipped. First came the fiscal. Both of these fiscal moves were proactive. The first one in COVID was proactive in the sense that first was reactive to the COVID slowdown. But we basically increased incomes, didn’t just match them. So there was a proactive element of the budget deficit in COVID that increased incomes without increasing production.

And then this period, this budget deficit over the last year, had a similar effect. You had the normal reaction to the tightening in terms of borrowing decline. You had a very different reaction in terms of consumption, and our belief on why is that you had built up significant cash balances on household balance sheets associated with the fiscal impact that has now been drained down, but that that created a support that more than offset these moves.

To be clear, we diagnosed this retrospectively. I wish I had known this before how it played out. But, to me, what’s interesting is the rate increase actually worked as normal on borrowing. It just didn’t work as normal on spending because there was another move.

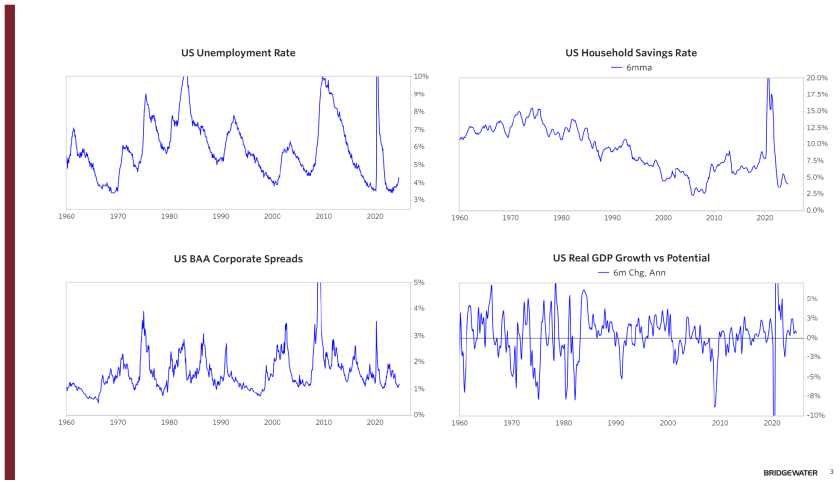

So if you look at the spending in the savings rate picture here, normally if you said, OK, well, what would happen if private sector borrowing fell? Normally, private sector borrowing falling would lead the savings rate to rise. But instead, the savings rate stayed low, and it declined all in this post-COVID period and stayed low. And growth stayed around potential because the decline in borrowing was offset by the fiscal impulse into households. So the actual linkages reverse when the government is the proactive player. It creates the spending. The savings rate stayed low because the cash on the balance sheet was able to be spent despite borrowing falling.

So to me, that’s how I see the mechanics of this, and when you play it forward, and this becomes the question—we’re going to find out how much the neutral rate or the rate that creates acceptable growth has changed if you don’t have a fiscal surge—what is it going to take for the private sector to restimulate the economy?

Because, for us, while you do have the fiscal problem that you’re saying, the secular problem, the cyclical fiscal impulse is behind us, in our view. And now you have to hand the economy back off to the private sector. And will the private sector, essentially—will borrowing start to increase again? You’ve had that decrease in borrowing, and you now have the wealth generated from the fiscal. That cash balance is pretty much spent. So can the private sector—and what will it take for the private sector to reignite spending?

And I think that becomes the big question going forward on whether the Fed’s going to ease 200 basis points or not, or more. I don’t think you’ve got any more fiscal impulse coming for a while, until the election and even post-election, depending on how it plays out. There’s a decent chance that fiscal is somewhat frozen—at a high level—but it’s somewhat frozen. And you now have to deal with what level of rates will cause the private sector to start borrowing again.

And you have two problems. The long-term thing happens in reverse now, and the point that Larry was making is that it’s hard to get people to refinance mortgages because most of the mortgages were set before the increase in rates. So if you actually had to get rates low enough to, let’s say, create a refinancing boom, you’d actually have to lower rates a tremendous amount.

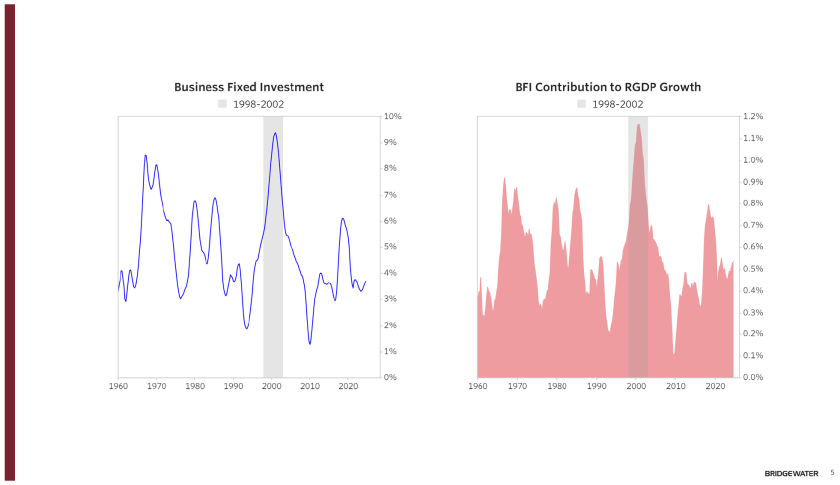

And so then there’s the question of how impactful is it on corporate borrowing. And I think it’ll be somewhat impactful. I think there’s a chance—and this gets into the AI thing—there’s a chance that a lower interest rate environment will help spur companies to take cash off their balance sheets—which they have a tremendous amount of—and do some significant increase in fixed investment. But it’s been interesting that fixed investment has been modest. It hasn’t surged. I mean, there’s a little bit of the deflator problem and the fact that capital is quite cheap.

But if you look at fixed investment and if you think about the fixed investment here, and you look at the annual change of business fixed investment—this is the bottom-left chart here. This is what it was like in the internet. You had this massive surge of fixed investment outside of any period. Here, I believe we’re on a technological revolution that’s super critical—we’ll talk a lot about AI at some point—and yet business fixed investment is quite low. I do think that’s the potential: if the economy’s going to boom from here, either it’s going to be because there’s some change in that fiscal policy goes back up, or in a significant way, or this environment is going to spur a boom along the lines of the late 1990s boom in business fixed investment, which I think is plausible. But you do have to see that happen, that even though AI spending is increasing right now, it’s been mostly instead of, not in addition to, instead of other types of investment.

And that becomes a big deal to say, OK, what is going to happen here going forward? Because I do think you have this handoff back from the government being the big leader in the economy back to the private sector.

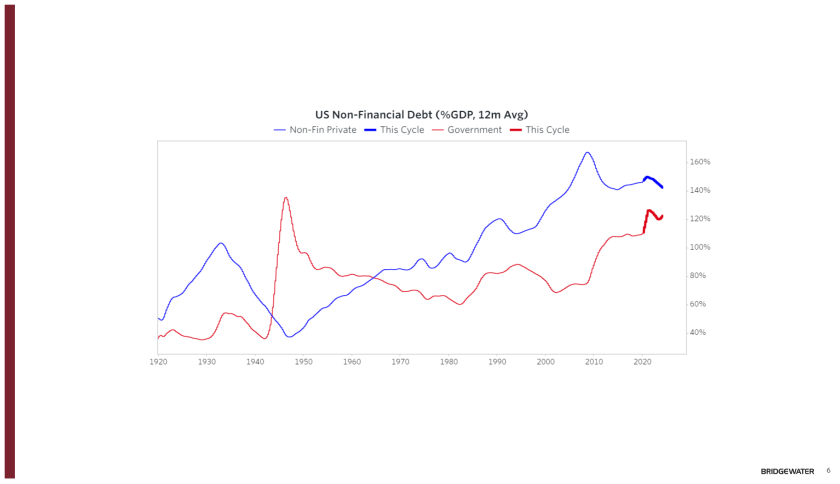

And so when we talk about how sustainable the public sector debt is, one thing that really does matter when you look at economies is the total. There’s the public, and then there’s the private. What has happened here is—like you said—this is World War II; this is the recent period. So you’ve got debts up near the levels of World War II for the public sector. At the same time, you’ve had the private sector debts come down during at least a big part of this surge in public sector debt. So this situation—the non-financial private debt is still not great or anything; you can look at that relative to history. But it’s well back to levels that it hasn’t been for a long time, and this is the handoff: you basically get private sector debt down, and in order to offset that, you’ve had the public sector [debt] rise significantly.

The last point I’d make is about inflation. The mechanics we see are that inflation fell in part because of the supply side; I won’t hit too much on that. But demand did fall. Demand fell because the fiscal impulse eased. Demand fell because the rates did have an effect; borrowing did decline a fair amount. And those things just netted because unlike private sector borrowing—that when you get the tightening, it kind of builds on itself—when it’s driven by fiscal policy, which isn’t even really affected by the Fed tightening, it can happen at a different rate than what you see when it’s driven by the private sector.

So those are some of our quick thoughts.

Chapter 5: Bob and Larry on the Outlook for the Dollar

Jake Davidson

Moving from economic conditions to markets, one of the more notable market moves over the past few years has been a significant rally in the dollar. Here’s co-CIO Bob Prince asking Larry and Bob their view on the dollar and what they’re watching as they think about the outlook from here.

Bob Prince

Bob, you’ve seen a lot of big cycles in the dollar—and there have been a lot of big cycles in the dollar, and you’ve probably really witnessed all of them, either through Goldman Sachs or Treasury or thereafter, including the ’70s, the breakup of Bretton Woods, then you have Volcker coming in and basically preserving the value of the dollar; your activities in the ’90s.

I’m really interested in your view of the dollar, particularly now given where it is, where it’s priced. On a real exchange rate basis, or however you look at it, it’s kind of at multidecade highs, at the same time as we have this massive supply of dollar debt out there, both on the outstanding stock, but also kind of continual rollovers and issuance of dollar debt going forward, at least by the government. Very interested in how you look at the dollar now.

Bob Rubin

I think the dollar over time—I don’t know about the short term. But, over time, I think it will be a function probably of two things. One is: how will our economy and our political system work? And I think there’s a great deal to be positive about with respect to our country—the dynamism, the entrepreneurialism, etc. And then there is what Larry suggested, which is we could screw it all up. For example, policy.

And then there’s the alternative: the rest of the world. I think China’s got a real problem. If you haven’t read it—you probably all have—but if you haven’t read it, you should read Adam Posen’s piece in Foreign Affairs about six months ago about the systemic issues that China faces—not the demographics and all the housing, all that stuff, but a much more systemic political issue, if you will, with respect to the direction of the party’s objectives, one thing or another. I think, now, what are the alternatives?

And then you have the EU—EU productivity growth from 2019 to 2022 was 0.4%. Ours was 6%. So they’ve got a lot of problems. Now they’ve asked Larry’s and my friend Mario Draghi to do a competitive study. It’s always good to do studies. But what are the alternatives?

Undoubtedly, the dollar will fluctuate up and down for all kinds of reasons. But I personally think, whatever it’s worth, that if we don’t screw up here politically, I think I’d stay in the dollar.

But, Larry, what do you think?

Larry Summers

I am inclined to the dollar serenity view, mostly because in the scenarios where things get pretty badly screwed up, it feels to me like they’ll get more screwed up for other places, or as screwed up for other places, as they will for the United States. So, you know, we might get a goofy, populist, nationalist president who does goofy, nationalist things, but I’m not sure that the day that happens, I’m going to be all that excited to have my money in Europe when NATO is being abandoned or Japan when a deal’s being cut on Taiwan, or in the Middle East when Iran’s being confronted. So I find it hard to get excited about getting out of the dollar on those kinds of grounds.

If I were running an endowment, I would spend meaningful time talking to people like you guys, trying to understand how much current safety premium was in gold and how much of current levels of gold demand were driven by industrial uses and the like. And if there wasn’t a lot of safety premium in gold, I would be looking to hold a bit of gold for the kind of reason that that’s where you go if all the places with paper currency are having trouble. But to form a view about that, I’d have to understand how much that was already priced in, and I don’t have a view.

I am struck that the real dollar is pretty strong right now. So if I frame the question as: suppose I was going to make a bunch of investments in European equities because I thought Europe looked cheap relative to the United States, would I be in a hurry to currency hedge those investments or not? I do feel like I’d be less keen to currency hedge those investments than I might be at a normal moment, which is kind of a way of expressing a little bit of concern about the dollar, given current levels.

Another question I would want to understand, which is the kind of thing you guys do sometimes, but I just haven’t looked at it recently—is if I take US real yields and I take Europe real yields and Japanese real yields, and I look at where the 10-year-forward real dollar is, does that look crazy to me or does that look reasonable?

My guess is that, because real interest rates are higher in the United States than they are in other places, there’s a bunch of depreciation already priced into where markets are and to where forwards are. I should probably only be short the dollar if I think it’s going to fall by more than what’s priced in, and I’m not sure that there’s that much more than is priced in.

Chapter 6: Larry and Bob on the US Fiscal Deficit

Jim Haskel

A related issue to the dollar and to the growth and inflation topics Greg and Larry discussed earlier is the impact of high government debt and deficits, because we’re now at a place where fiscal deficits are near secular highs and with virtually all credit creation in the economy coming from the government as opposed to the private sector. So the natural question is whether this situation is sustainable and what its effect will be.

Here’s Larry and Bob on that topic.

Larry Summers

Let me just comment on one issue where I think Bob and I have somewhat different—but not completely different— views and are more converged than we have been at some points in the past. And that’s budget deficits.

Bob can speak for himself, and no doubt will, but I think it’s fair to say that he is in a fairly permanent state of alarm about excessive budget deficits and regards the prospect that America will overdo fiscal restraint as roughly paralleling the risk that I will go on some program that will cause me to become dangerously thin—that anything’s possible, but certain risks are really pretty remote.

I have a rather different view. I think of fiscal policy in the context of the structural features that are driving private saving and private investment. When it seems to me that the economy is in danger of producing a chronic excess of private saving over private investment, even at very low interest rates, I think that really quite expansionary fiscal policy is healthy and appropriate (a) because the very low level of interest rates makes it sustainable and (b) because it’s necessary, because I think economies operating at near-zero interest rates are prone to various kinds of financial misbehavior, financial excess, and bubbles.

So I don’t think the country was worse off between 2011 and 2019 because Simpson-Bowles wasn’t implemented. I actually think that if Simpson-Bowles had been implemented, given that we were already at zero interest rates and massive QE, there would have been a systematic risk of excessive deflation and disinflation without a healthy tool—because there wouldn’t have been any room for long rates to fall and so there wouldn’t have been any offsetting expansionary impulse. So I was very much not a fiscal hawk in the 2011-19 period. And I would stand by those judgments.

But in economics, unlike physics, you have to adjust your way of thinking to the fact that the world changes quite profoundly. And in the aftermath of the big run-up of debt and the many reasons to have real interest rate increases, it has seemed to me since 2021, with growing degrees of alarm, that we have a very, very serious fiscal situation developing, which is likely to manifest itself in one of substantial inflationary pressure, substantial indigestion in the Treasury markets with financial chaos, or substantial crowding out of what would be otherwise valuable private investment.

Bob Rubin

I’ll be very brief. Leaving aside the history of the fiscal policy and, as Larry said, we have somewhat different views, —we could debate whether that was a useful thing to have; my views were useful or not useful.

I think, looking forward, the CBO says the debt-to-GDP ratio now is about 98% or 100%. And they project 10 years out at 122%. I think most people think that as the CBO is bounded by current law, that a more realistic number is 130%, 135% or something like that, given geopolitical challenges and climate change. I believe I’m right in saying that the highest we’ve ever had was 106%, and that was the end of World War II. So we are into uncharted territory, and I’ll continue to think, as I have thought, and—although Larry doesn’t agree with this—I think it’s been constructive to have had this perspective over time in terms of constraints, however limited they may have been.

I think it’s a tremendous risk. And I think Larry briefly outlined what those risks could be. I think the politics of dealing with it are impossible because almost all Republicans in Congress have signed a little thing saying they’ll never raise taxes. Democrats are unwilling to deal with entitlements. And yet that’s where the ball games are in those two places.

I’ll make one other observation. If you take the year 2000 to the year 2022, I believe it was something like 45-50% of the increase in the debt was a result of two tax cuts—2011 and 2017. And whatever one may think about all sorts of issues, substantively, politically, ideologically, whatever it may be, I think an awful lot of it—and then if you look at the spending side of the budget, and you say what national security is likely to do and you consider what the nondefense discretionary consists of, there is stuff you could do on the entitlement side, but I do think most of the solution is going to have to be the tax side. And the politics of that, as I said a moment ago, I’m very troubled about it. I don’t see how we get out of this.

As Larry said, and I think he’s right—or he sort of said; I guess his thoughts were leaning in this direction—there could be all sorts of negative consequences as we go along the route: higher interest rates, something to do with the dollar, dynamics in the Treasury market. But at the end of the game, unless something changes politically—I mean, changes a lot—I think there’s a real risk of some kind of financial crisis. And even in a financial crisis, how do we know our two parties would be able to work together?

Chapter 7: Larry on Artificial Intelligence

Jim Haskel

And finally, here’s Larry Summers, an OpenAI board member. And he discusses his thoughts on AI and its impact on the economy, and you’ll hear him address the potential pace of AI’s impact and the types of jobs it might disrupt.

Larry Summers

My general reading on all technologies is that they happen slower than you think they would, and then they happen faster than you thought they could. And I remember Bob and I had a conversation—Bob, I don’t know if you remember this—in 1998, probably, or maybe it was early 1999. The young Jeff Bezos came for a business lunch at the Treasury, and we had a discussion, the general thesis of which was, gosh, we should be shorting shopping malls if we were investors. And that was basically a wrong insight for anyone who was trading rates at that moment. And it was basically a deep truth about the next 25 years.

Bob Rubin

General Growth did go bankrupt eventually.

Larry Summers

What you and I talked about, we had exactly the right conclusion. But as an actionable insight for the next five years, we were more wrong than right. And as a deep truth about the next 25 years, we were exactly right.

Similarly, if you’d asked me in 2000 when there would be electronic readers, I would have gotten it way early. And if you’d ask me in 2010 how likely it was that I’d stop reading physical newspapers by 2017, I would have thought that was really quite unlikely. So I think the rule “slower than you think and then faster than you thought they could” is a very powerful rule for thinking about AI and these other things.

The other two comments I’d make about AI are that it will come for IQ before it comes for EQ. Therefore, it may change a lot of relative valuations of different skills in quite profound ways and quite different ways than technologies have in the past. Frankly, it’s going to come for the skills of the people on this call more quickly than it’s going to come for the skills that salesmen and nurses have. And so I think it can lead to some quite profound changes in how it’s going to be seen. I suspect the fact that it comes fairly quickly for the skills of people who write articles is going to lead to some potential tendency toward exaggeration in what we read about its significance and the rapidity of its significance in the economy.

And the last thing I would say is I think there is a kind of category error in a lot of the discussion, which tends to always focus—as this one has so far—on this job category and that job category, and what’s it going to mean for jobs, and what’s it going to mean for disruption? And there’s another way to think about it, which is suppose the pace of scientific progress—whether it’s stuff like sequencing the genome or proving new theorems in math or understanding quantum physics—suppose the pace of scientific progress triples. How does that change the world? And the answer is probably “profoundly,” but you won’t necessarily get that right thinking in terms of specific job categories. And my sense is that there’s potentially quite large changes in the rate of scientific and technological progress.

…