Link para o artigo original: https://www.bridgewater.com/research-and-insights/are-we-on-the-brink-of-an-ai-investment-arms-race

At some points in history, we experience a technological breakthrough big enough to change the way that we go about our day-to-day lives. In most cases, it takes many years for society to adapt to the new technology and to figure out how to reap its benefits. However, the combination of excitement around its potential benefits and fears of becoming obsolete can spark intense competition to get ahead. That competition can pull forward the expected future growth associated with the technology by creating a surge in investment in the near term.

We believe AI is likely on that path. We have been studying AI for over a decade, both as macro investors interested in its possible economic impacts and as users of machine-learning techniques (and, for a few of us, as individual investors in the space). Since the release of ChatGPT in the fall of 2022, the technology has captured the imagination of society—and, while its ultimate impact on the economy remains highly uncertain, it may boost productivity across many industries in truly staggering ways.

Today, the ingredients are in place for an arms race to build capability in AI. In investment management, the race is on. Over the next decade, investors who most effectively harness the strengths of machine learning and navigate its weaknesses will likely build sizable economic moats. This is likely true across most industries; as that becomes increasingly clear, spending on AI will accelerate. Already, the technology is an existential concern for some of the world’s most cash-rich companies (mostly in tech), and some of the largest pools of capital are jockeying to capture its future benefits. Over the next two years or so, we expect that new entrants will use ML techniques to disrupt several established industries, likely prompting another wave of investment far beyond the tech industry.

Even if the productivity gains for the average company are years in the future, the spending to get there could have material implications for growth and corporate profits in the near term. To appreciate the possible magnitude of this investment, consider: how much will people with cumulative access to trillions of dollars invest if they believe their companies are at existential risk? How much capital will become available if investors believe a new technology has almost unlimited possible future value? It will not take many players to feel that way for the resulting investment to have major economic ripples. Indeed, investment around the adoption of computers and the internet—the last major period of investment to integrate a general-purpose technology—was an important driver of growth in the ’90s. If anything, the concentration of AI investment among a few very cash-rich players means that it could ramp up faster and with less of a connection to realized productivity gains than investment did then.

Of course, nothing is certain yet, and we continue to track the market pricing and cash flow expectations of the key players across the exposed supply chains. Notwithstanding some pockets of froth, the classic boom dynamic of abundant capital chasing far-out returns has yet to take off: affected firms’ equity prices are mostly moving in line with near-term expected profits at reasonable or only slightly stretched multiples. But when we look at the underlying dynamics, we see the makings of a surge in spending that could be large enough to shape the trajectory of the business cycle from here.

In the rest of this report, we explore these dynamics in greater depth and take stock of where they stand today.

Investment to Adopt General-Purpose Technologies Can Drive the Business Cycle

Like past general-purpose technologies, the widespread adoption of AI across the economy would require the build-out of an extensive infrastructure to support it. The diagram below provides a simplified sketch of the flow of AI-related spending through the relevant supply chains, noting where some high-profile companies fit in.

There is a very wide range of possibilities for how much investment will ultimately occur across these supply chains. We are still in the early innings of adoption: core models have limited utility on their own, and people will need to figure out and build effective applications of the technology before it can add value across a wide range of industries. In the long run, the magnitude of investment will depend on the evolution of highly uncertain variables, such as the speed of adoption of the technology, the degree of AI use across the economy, the size of large language models, industry concentration (e.g., does everyone use just a few models or will many models be trained in parallel?), and hardware and software efficiency gains. However, past precedent can provide us with a sense of the amount of investment that is plausible—and historically, major technological transitions have fueled investment increases that were large enough to shape the overall business cycle.

Below, we illustrate the period of investment around the adoption of computers and the internet, which similarly required wide-ranging investment, from chips to fiber-optic cables to software. This investment was concentrated in the eight years between the early ’90s recession and the end of the dot-com bubble, as mounting enthusiasm around the technology gave rise to a prolonged period of abundant capital that funded capex. This period saw the greatest average annual increase in business investment of any period of that duration over the last 60 years—leading to a cyclical expansion that was driven much more by business investment than were past business cycles (alongside a major asset-price bubble). In the coming years, AI may well produce economic benefits similar (or much greater) to the computer, suggesting that we are plausibly on the precipice of a similarly impactful surge in investment. As we explore below, we could even see a ramp-up in investment that is faster and more disconnected from realized productivity gains than in the ’90s, given the concentrated nature of AI-related capex among a few cash-rich players.

AI Is Increasingly Seen as Existential by Companies and Investors with the Capacity to Spend, Creating the Conditions for a Wave of Investment

Corporate investment is typically reactive, following broader cyclical conditions with a lag as businesses respond to shifts in end demand for their products. But it can be proactive when there are enough companies or investors with both the incentives and the ability to make more speculative bets. We think these two conditions are in place for AI today.

The incentives to move quickly on AI are clear. While there is a high degree of uncertainty around how AI will impact the economy, many expect it to generate a tremendous amount of economic value—creating both significant opportunities for those who might be able to capture that value and significant risks for those who might be left behind. We wouldn’t be surprised if AI lifted productivity growth by around one to three percentage points in the coming decade, translating to trillions of dollars in additional economic activity.

We are still far from that world: without effective application, the core technology alone has limited utility, and AI is not yet a major driver of productivity growth outside of a few use cases (like software engineering). The Census Bureau’s Business Trends and Outlook Survey indicates that only 5% of companies use AI regularly to produce goods and services, with less than 0.4% of companies reporting that even a “moderate” number of labor tasks have been automated by AI. Meanwhile, macro data does not indicate large productivity gains in most of the sectors where AI adoption is proceeding fastest. But expectations about the future benefits of AI don’t need to be universally held to induce tremendous investment, so long as some of the key actors believe them. In the near term, those key actors are likely to be large corporations (particularly in tech) and some of the world’s large pools of capital.

For many of the largest tech firms (and some outside of tech), AI creates both the risk that their existing core businesses will be rendered obsolete and the unique opportunity to leverage their client relationships and resources to outcompete others in providing AI tools (for instance, by integrating AI into their existing services or by using access to proprietary data and technical talent to develop superior AI products). In addition to developing AI-powered services, cloud-service providers like Amazon, Google, and Microsoft have the opportunity to enable the build-out of AI by providing the compute that others need to develop and to use AI.

Today, the leaders of these firms are increasingly characterizing AI as an existential issue, often explicitly comparing it to the technological shifts that gave rise to their current businesses. Below are some examples from their most recent earnings calls:

- Alphabet: “The AI transition, I think it’s a once-in-a-generation kind of opportunity”; AI “impacts the entire breadth of the company”; and “[it] is going to impact every product across every company.” (CEO Sundar Pichai)

- Amazon: “I don’t know if any of us have seen a possibility like this in technology in a really long time, for sure since the cloud, perhaps since the internet.” (CEO Andy Jassy)

- Apple: “We believe in the transformative power and promise of AI” and “we see generative AI as a very key opportunity across our products.” (CEO Tim Cook)

- Meta: “There are several ways to build a massive business here”; “we should invest significantly more over the coming years to build even more advanced models and the largest-scale AI services in the world…[We’ll] grow our investment envelope meaningfully before we make much revenue from some of these new products.” (CEO Mark Zuckerberg)

- Microsoft: AI adoption is like “the PC when it became standard issue in early ’90s, that’s the closest analogy I can come up with.” (CEO Satya Nadella)

Not only do these firms have a strong incentive to take advantage of this perceived “once in a generation” opportunity—they also have significant resources to devote toward that aim. They are some of the richest companies in history, with both massive war chests of cash and highly profitable core businesses that can fund more speculative investments. While we wouldn’t expect them to spend down all their resources, even in response to an existential pressure, the charts below give a sense of the magnitude of the resources available to them—without even including their ability to secure the equity and debt financing that is the typical fuel of investment booms.

Alongside these companies, some of the world’s wealthiest investors are starting to describe AI in existential terms and to commit large sums to investing in it. Some of those investments will go directly to firms building out the physical infrastructure associated with AI; many of them will go toward startups in the AI applications space, thereby creating intermediate demand for cloud-service providers that will support those providers’ investments in physical infrastructure (for instance, over 60% of funded generative AI startups are Google Cloud customers). While we are still in the very early stages, a capital-raising boom may be emerging. The table below provides some examples.

In a classic boom, businesses don’t need much cash to fund their capex, as investor enthusiasm fuels significant equity and debt financing. But even without this dynamic, American companies are well-positioned today to invest in new technologies, which may accelerate investment in AI relative to past investment booms: corporate cash balances are historically high after pandemic-era stimulative policies and profit levels are similarly around secular highs amid a broadly strong cyclical environment. While investment in AI will likely be concentrated in the near term among the tech companies for whom it is already clearly existential, almost every major corporation is facing pressure from their boards to devise a plan for AI. Many have the resources to respond either by developing their own AI-powered tools or by paying for AI services from tech firms, thereby supporting demand for AI products even before they meaningfully enhance productivity (for example, over 65% of Fortune 500 companies are now using Microsoft’s Azure OpenAI Service). In the coming years, we expect that a few major earnings success stories from businesses applying AI to disrupt established industries will turn AI into a pressing issue for a wide swath of companies beyond tech, unleashing a much larger wave of investment.

So Far, AI Capex Is a Small Part of the Economy, but It Is Poised to Pick Up in the Near Term

Today, AI-related capex is still a small share of the economy: spending on AI chips and data centers was a bit below $100 billion in 2023 (around 0.4% of US GDP). The charts below illustrate how that investment has evolved recently. As we show at left, while chip company revenues have spiked (driven by NVIDIA), the broader ecosystem of companies exposed to AI-related investments has yet to see a major jump in sales since AI enthusiasm took off following ChatGPT’s November 2022 launch. Meanwhile, capex for the major cloud-service providers—the narrowest point in the investment chain—reached new highs as a share of the economy in the last quarter. However, these firms’ capex is still growing in line with longer-term trends, not yet accelerating beyond them in response to acute pressures to build out AI.

Both equity pricing and analyst forecasts reflect expectations for a material rise in AI-related investment from here. Across the AI capex ecosystem, companies have outperformed the S&P 500 by a wide margin over the past year or so, with the greatest increase in valuations among the most direct near-term beneficiaries of AI-related investment (chip suppliers) and a more recent and modest increase among less direct beneficiaries, like those exposed to AI-related power demand. However, we are still far from a classic investment boom. While some pockets of the ecosystem look frothy, increased valuations today mostly do not resemble an asset price bubble; rather than rising well above short-term earnings expectations, as they did in the dot-com bubble, prices have risen roughly in line with short-term earnings expectations. Indeed, the shift in expectations so far may well be too modest given both the existential nature of AI for some of the wealthiest players in the economy and the magnitude of investment that groundbreaking technologies can induce. That said, the earnings growth expected for these firms in the short term is a product of investment that is itself speculative, in the sense that it is mostly not justified by existing productive uses of the technology; this spending would fade if AI does not live up to its potential.

Supply Constraints That Risk Slowing the Pace of AI Adoption Will Shape the Flow of Investment, Redirecting Resources Toward Bottlenecks

As we saw over the past year, rapid increases in demand for items like chips cannot be met immediately. Supply bottlenecks will slow the adoption of AI across the economy by raising the cost of compute. Given the high degree of interest in AI, such bottlenecks are likely to induce significant investment to resolve them, shaping the complexion of investment in AI. While shortages can limit spending on items farther down the supply chain from them, they likely won’t limit the aggregate amount of AI-related investment or the speed with which that spending ramps up, but instead redirect spending farther up the supply chain to resolve bottlenecks.

Over the past year, the chip bottleneck sparked a wave of interest in chip-related investments. NVIDIA’s very large margins (around 60%) helped to attract other firms into the AI chip space to compete, from startups to some of the world’s largest firms; TSMC invested billions of dollars into a new chip packaging plant to alleviate short-term constraints; and Sam Altman embarked on a high-profile quest to raise trillions of dollars for chip fabrication facilities, among other examples.

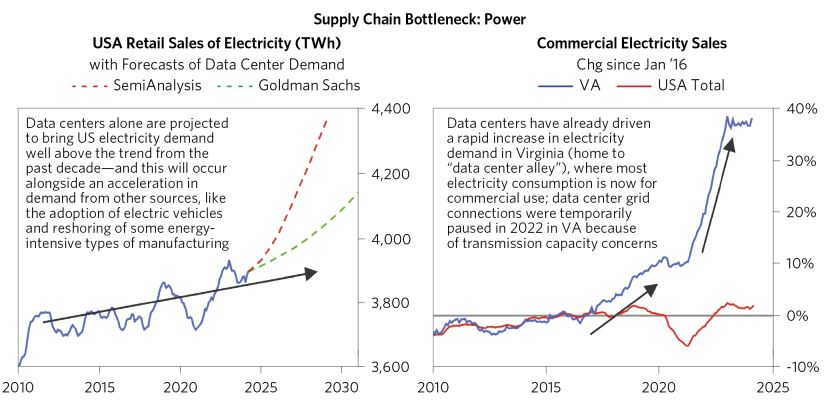

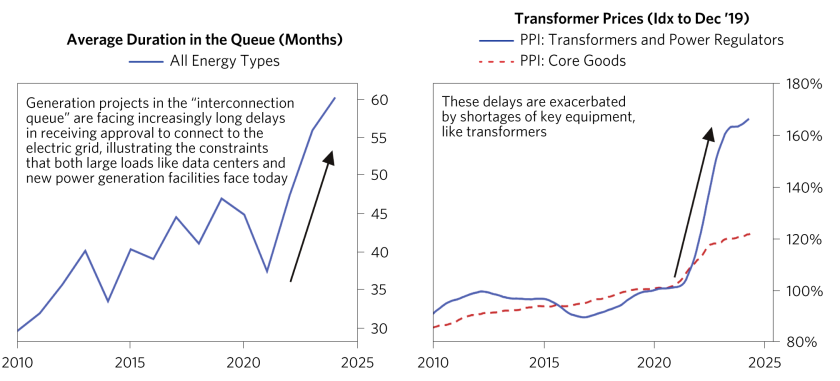

While chip supply constraints have eased somewhat (e.g., wait times for NVIDIA shipments have declined by roughly 3x), another bottleneck is now emerging around the significant power needs of AI data centers. Data centers alone are projected to drive aggregate US electricity demand far above its long-term trend in the next few years, as shown below at left, and power forward prices have moved higher in response to expectations of increased load demand. Existing transmission and distribution systems cannot handle the new demand and supply coming online, and there are both physical constraints on building out these systems (shortages of critical infrastructure, like transformers) and an oft-cumbersome approval process that can make new construction a slow process.

This bottleneck will likely be harder to address than the bottleneck for chips, given the degree of regulatory oversight. But it will also attract increased investment to resolve it. In addition to inducing spending from utilities and independent power providers, it is driving data center builders themselves to explore various “behind the meter” power solutions (often at greater cost). There is even growing interest in “off meter” approaches that would obviate the need to connect projects to the power grid altogether (but face practical hurdles, particularly in the context of some cloud service providers’ green energy commitments). Some utilities are also pushing for new data center projects to make longer-term payment commitments to support investments for the required infrastructure.

This research paper is prepared by and is the property of Bridgewater Associates, LP and is circulated for informational and educational purposes only. There is no consideration given to the specific investment needs, objectives, or tolerances of any of the recipients. Additionally, Bridgewater’s actual investment positions may, and often will, vary from its conclusions discussed herein based on any number of factors, such as client investment restrictions, portfolio rebalancing and transactions costs, among others. Recipients should consult their own advisors, including tax advisors, before making any investment decision. This material is for informational and educational purposes only and is not an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to buy the securities or other instruments mentioned. Any such offering will be made pursuant to a definitive offering memorandum. This material does not constitute a personal recommendation or take into account the particular investment objectives, financial situations, or needs of individual investors which are necessary considerations before making any investment decision. Investors should consider whether any advice or recommendation in this research is suitable for their particular circumstances and, where appropriate, seek professional advice, including legal, tax, accounting, investment, or other advice.

The information provided herein is not intended to provide a sufficient basis on which to make an investment decision and investment decisions should not be based on simulated, hypothetical, or illustrative information that have inherent limitations. Unlike an actual performance record simulated or hypothetical results do not represent actual trading or the actual costs of management and may have under or overcompensated for the impact of certain market risk factors. Bridgewater makes no representation that any account will or is likely to achieve returns similar to those shown. The price and value of the investments referred to in this research and the income therefrom may fluctuate. Every investment involves risk and in volatile or uncertain market conditions, significant variations in the value or return on that investment may occur. Investments in hedge funds are complex, speculative and carry a high degree of risk, including the risk of a complete loss of an investor’s entire investment. Past performance is not a guide to future performance, future returns are not guaranteed, and a complete loss of original capital may occur. Certain transactions, including those involving leverage, futures, options, and other derivatives, give rise to substantial risk and are not suitable for all investors. Fluctuations in exchange rates could have material adverse effects on the value or price of, or income derived from, certain investments.

Bridgewater research utilizes data and information from public, private, and internal sources, including data from actual Bridgewater trades. Sources include BCA, Bloomberg Finance L.P., Bond Radar, Candeal, Calderwood, CBRE, Inc., CEIC Data Company Ltd., Clarus Financial Technology, Conference Board of Canada, Consensus Economics Inc., Corelogic, Inc., Cornerstone Macro, Dealogic, DTCC Data Repository, Ecoanalitica, Empirical Research Partners, Entis (Axioma Qontigo), EPFR Global, ESG Book, Eurasia Group, Evercore ISI, FactSet Research Systems, The Financial Times Limited, FINRA, GaveKal Research Ltd., Global Financial Data, Inc., Harvard Business Review, Haver Analytics, Inc., Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS), The Investment Funds Institute of Canada, ICE Data, ICE Derived Data (UK), Investment Company Institute, International Institute of Finance, JP Morgan, JSTA Advisors, MarketAxess, Medley Global Advisors, Metals Focus Ltd, Moody’s ESG Solutions, MSCI, Inc., National Bureau of Economic Research, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Pensions & Investments Research Center, Refinitiv, Rhodium Group, RP Data, Rubinson Research, Rystad Energy, S&P Global Market Intelligence, Sentix Gmbh, Shanghai Wind Information, Sustainalytics, Swaps Monitor, Totem Macro, Tradeweb, United Nations, US Department of Commerce, Verisk Maplecroft, Visible Alpha, Wells Bay, Wind Financial Information LLC, Wood Mackenzie Limited, World Bureau of Metal Statistics, World Economic Forum, YieldBook. While we consider information from external sources to be reliable, we do not assume responsibility for its accuracy.

This information is not directed at or intended for distribution to or use by any person or entity located in any jurisdiction where such distribution, publication, availability, or use would be contrary to applicable law or regulation, or which would subject Bridgewater to any registration or licensing requirements within such jurisdiction. No part of this material may be (i) copied, photocopied, or duplicated in any form by any means or (ii) redistributed without the prior written consent of Bridgewater® Associates, LP.

The views expressed herein are solely those of Bridgewater as of the date of this report and are subject to change without notice. Bridgewater may have a significant financial interest in one or more of the positions and/or securities or derivatives discussed. Those responsible for preparing this report receive compensation based upon various factors, including, among other things, the quality of their work and firm revenues.